13.2 Enhancing Self-Control

Jay Brown

Enhancing Self–Control

by Jay Brown, Ph.D.,

with Wyn Taylor and Marisol Bazaldua

Most decisions we make place us between two choices. Usually one of these choices is easier or more fun at the moment, perhaps even illegal or immoral. The other choice is usually harder or less fun at the moment. Ironically, the easy and fun choice tends to lead to bad outcomes in the long-run, whereas the hard choice tends to lead to good long-term outcomes. Self-control refers to the control of behavior using internal controls (such as diligence or morality) rather than external controls (such as rules and laws). Behaviorally, individuals are said to exhibit self-control when they choose that thing which is harder at the moment and bypass the easier thing. Similarly, individuals are said to exhibit impulsiveness if they choose the thing that is easier or more fun at the moment. Examples of self-control choices abound in our lives. A student who has a test in the morning that chooses to stay home and study is exhibiting self-control. A classmate in the same situation who instead chooses to go to a party is exhibiting impulsiveness (Rachlin, 2000). The ability to make self-controlled choices is probably the most important skill one can achieve in one’s life and the greatest gift we can teach our children. Success in life always requires us to bypass momentary pleasures. If you want to be financially successful (“rich!”), you must bypass the pleasures that spending your money right now could provide (a yummy cheeseburger perhaps) and instead invest it for a larger return in the long-run. If you want to be spiritually successful, you must bypass the pleasures you could receive on Sunday morning by sleeping in and instead go to church regularly. If you want to be successful in college, you must bypass the short-term pleasures you could receive by going to parties or watching television and instead spend the time studying. If you want to be … alright you get the idea: ALL success comes through self-controlled choices (Rachlin, 2000). Though some of us are better than others at making self-controlled choices, all of us fall short of our full potential when we occasionally act impulsively. Often, when we are making bad choices, we know we are making bad choices but we do it anyway. Why? The outcomes of impulsive choices tend to feel good now, whereas the outcomes of self-controlled choices tend to feel bad now. When given the choice, the dieter clearly knows that dessert is going to taste and feel good now, whereas skipping dessert is not going to be fun. Even a baby knows that dessert tastes good; jars of Gerber desserts are much easier to feed a baby than jars of Gerber strained peas. However, the long-term consequences of dessert eating are less clear and need to be learned. It is only through experience that we know that skipping dessert tends to lead to weight loss and that eating dessert leads to weight gain. One of the reasons we fail to make self-controlled choices is that we do not yet have enough experience to know the long-term consequences of our choices.

However, a dieter does not need to learn the long-term outcomes of dessert eating exclusively from his/her own experiences. We can also learn, through a process called social learning, about the long-term consequences of our choices by seeing what happens to others. In college, I had a dorm mate that made bad choices (sleeping in, partying, etc.) and really quickly failed out of school. I was able to learn from the experience. I concluded that if I made the same types of choices, I would probably suffer the same fate. I was able to anticipate the probable long-term consequences of a series of choices without having experienced the consequences myself This is the way social learning is supposed to work. However, I remember a television program called Beverly Hills 90210which featured a bunch of spoiled high school kids with silly problems. As the show progressed, the kids got too old for high school, so they all “graduated”. Almost all of them went to an elite university (Stanford I think). The funny part was, during the years the program revolved around high school, we never saw those kids studying; we only saw them out having fun and having personal crises. What lesson might a naive person pull from this? Partying and having fun are the way to get admitted to a good university! If anyone really believed this, then it could definitely explain at least some of the bad choices we make. In a more believable way, advertising’s job is to make us fail to understand the consequences of our choices. Beer commercials always feature people having fun, never the hangovers or the severe consequences of alcohol addiction.

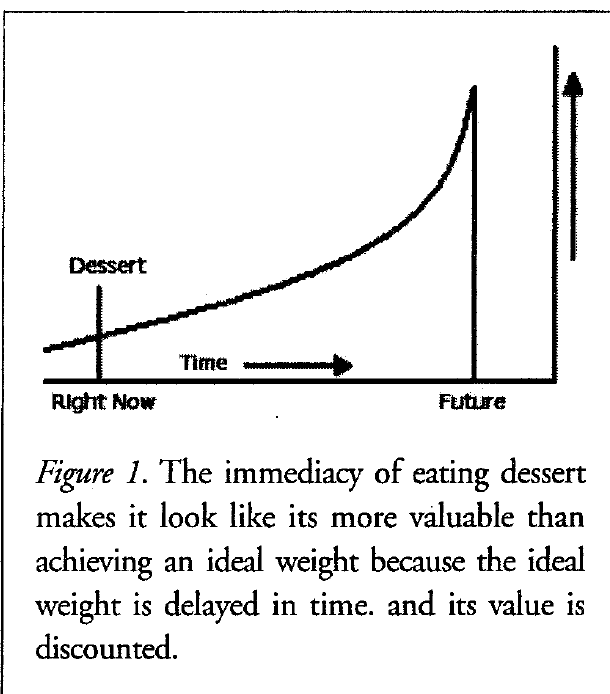

Another common reason we fail to exhibit self-control is delay discounting. Quite simply, a promise of $20 which you are to receive today is more valuable than a promise of $20 which you are to receive in a year (Rachlin, 1991). The value of the $20 is discounted (lost) when its receipt is delayed. The person

Another common reason we fail to exhibit self-control is delay discounting. Quite simply, a promise of $20 which you are to receive today is more valuable than a promise of $20 which you are to receive in a year (Rachlin, 1991). The value of the $20 is discounted (lost) when its receipt is delayed. The person

trying to lose weight is faced with the following dilemma: eating dessert feels good right now, whereas not eating dessert feels bad right now. Because these consequences are immediate, their values are not discounted. However, the long-term consequences of eating dessert are bad, whereas the long-term consequences of not eating dessert are good. The value of these long term consequences, since they are delayed in time, is discounted. Even though the long-term consequences of eating dessert include weight gain, the very thing the dieter is trying to avoid, the weight gain doesn’t occur until some distant point in the future, a point which is hard to see and therefore has little impact on decision-making today. As can be seen in Figure 1, the value of dessert right now appears to be more valuable than weight loss due to the immediacy of the dessert.

Box 1. Keeping in line with the title of this article, we can use our understanding of the curve in Figure 1 to help us enhance our self-control. If you are trying to quit smoking, then Figure 1 could be modified so that the shorter bar represents the value of smoking whereas the taller bar represents the value of good health, the difficulty in making the right choice remains the same. However, if one could somehow lower the value of smoking or raise the value of not smoking, the story would be different. When I was quitting smoking, this is exactly what I did. To raise the value of not smoking, I gave myself an extra reward: any day that I didn’t smoke, I allowed myself to buy any candy I wanted (one of my other vices). However, lowering the value of smoking was a more difficult task. I was living in Pittsburgh, PA at this time and it was February, definitely not a good time to be a smoker who is stuck outside. I made sure to watch all the smokers huddled outside my building and told myself that was what I had looked like when I smoked, not very bright looking. This effectively took away some of the value of smoking. I was able to raise the value of not smoking a little bit and lower the value of smoking a little bit; it was enough that the value of smoking at the moment was lower than the value of not smoking at the moment.

The consequences of our actions, especially the long-term consequences, are uncertain (Brown & Rachlin, 1999; Brown & Lovett, 2001). If it were possible to know that smoking was guaranteed to give you lung cancer and make you die a painful death, no one would smoke. This is not how the world works. Instead, the probability of getting lung cancer and dying a painful death increases if you smoke and decreases if you don’t smoke. This uncertainty makes self-controlled decision-making even harder. The smoker that is contemplating quitting might say, “My great aunt Ruth smoked 3 packs a day and she lived to be 109!” or “My cousin Bob quit smoking, but then got hit by a bus the next day.” Even though the truth is that smoking increases the probability of lung cancer, these vivid cases are in some ways more convincing (especially to the smoker that is looking for justification anyway).

When students are asked for the probabilities of events they experienced during an experiment, the most common response given is 50%, indicating that they believe it was a random process, despite the fact that in actuality the event occurred 85% of the time. People have an unfortunate tendency to equate a probability they don’t understand with randomness and unpredictableness. Though the long-term consequences of our decisions are probabilistic, that does mean they are either random or unpredictable (Brown, 2006). We hypothesize that in a situation where the long-term consequences of choices are uncertain, giving people accurate information about the probabilities of the long-term outcomes will increase their ability to make self-controlled choices.

Method

Participants and Apparatus

One-hundred and twenty-four undergraduate students taking psychology courses participated in this experiment. All students were enrolled at Texas Wesleyan University and were tested between January 2007 and April 2008. A computer program written in Microsoft Visual Basic specifically for this research was used to present stimuli. The program was presented on a pair of Nobilis laptop computers.

Procedure

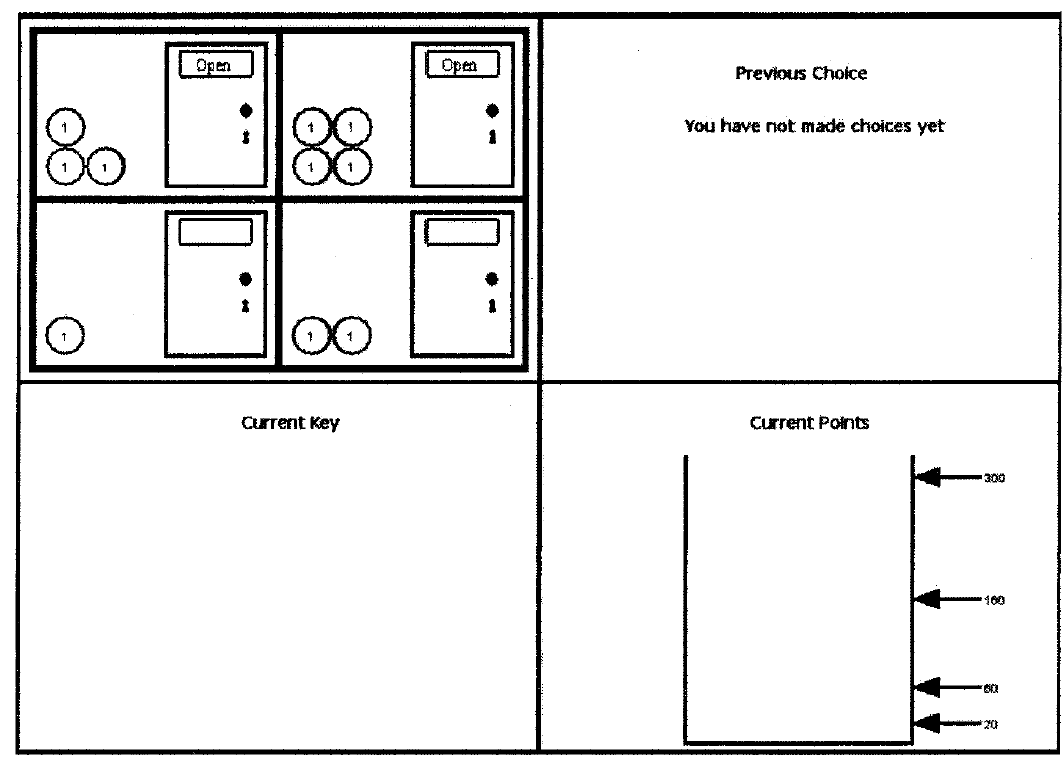

Participants were seated at the computer and an instruction screen appeared. On this screen, the rules of the game they were to play were presented along with a demonstration on a game board (see Figure 2 for a simplified version of the game). The rules can be summed up as follows:

- Red keys open red doors, green keys open green doors.

- When a door is opened, the player receives the points and key from the opened door, but gives up the key just used.

- The game repeats for many trials.

- The goal is to make as many points as possible.

Figure 2. Game used in the experiment.

In this game, players face a dilemma. The doors on the right side contain more points than the doors on the left side. If the participant has a red key, s/he can open doors containing three or four points. If the participant has a green key, s/he can open doors containing one or two points. In either case, participants receive more points on the current trial by opening the door on the right side. However, the top doors contain more points than the bottom doors. The only way to be able to open a door on the top is to have a red key. The only way to get red keys is to choose doors on the left side. Participants want to open doors on the right and doors on the top, and these are incompatible goals. The solution in this game (and all manipulations described) is continual choice for the left-side doors. Self-control is defined in this game as the percent of choices for the left-side since these choices lead to worse consequences on the current trial (fewer points) but better consequences on subsequent trials (red keys).

When participants played the game, all keys except the current key were not visible; instead, the keys were only revealed after each choice was made. For some participants, the keys were 100% predictable; for example, opening the top left door always led to a red key. For other groups, the keys were 87.5% predicable, 75% predictable or 62.5% predictable. As an example, in the 75% predictable group, if the top right door was chosen, then there was a 75% chance that a green key would appear to be used on the next trial and a 25% chance that a red key would appear for use on the next trial.

Additionally, participants were divided with half receiving feedback and half receiving no feedback. For those in the feedback group, a message appeared between each trial informing the participant how many choices they had made for each door as well as the keys they had received, for example, “You have opened the top left door 36 times and have received a red key 31 times and a green key 5 times.” Participants in the no feedback group simply received a message a button with the message “Press to continue.”

Additionally, participants were divided with half receiving feedback and half receiving no feedback. For those in the feedback group, a message appeared between each trial informing the participant how many choices they had made for each door as well as the keys they had received, for example, “You have opened the top left door 36 times and have received a red key 31 times and a green key 5 times.” Participants in the no feedback group simply received a message a button with the message “Press to continue.”

Results and Discussion

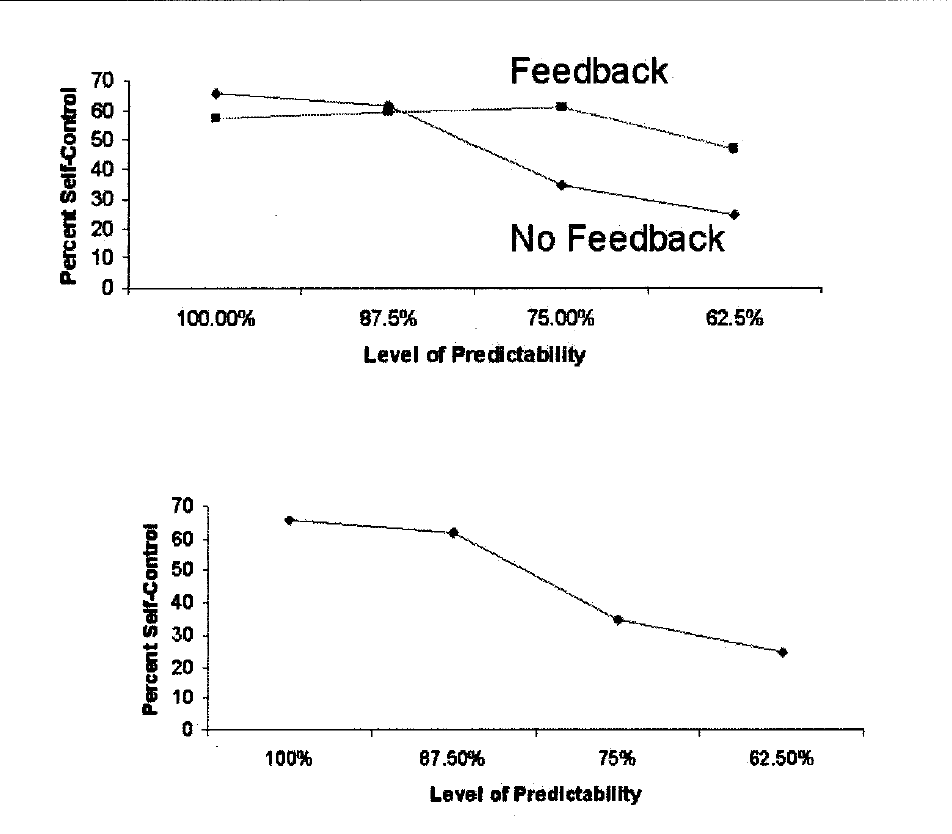

When considering the no-feedback group exclusively, there is a dear pattern seen in Figure 3 such that as the predictability of the game went down (the ability to predict long-term consequences), self-control went down, F(3, 57) = 16.88,p < .001. Additionally, feedback was shown to be effective (see Figure 4), but only in those cases where long-term consequences were the most unpredictable, F(3, 116) = 6.54, p < .001. Feedback increased self-control when the level of predictability was low (62.5% and 75%) but seemed to have little impact when predictability was high (87.5% and 100%).

Conclusion:

So How Can This Study Help Me Enhance my Self-Control?

Figure 3. Percent of choices for the left side of the game (self control) as a function of the participant’s ability to predict the long-term consequences of their actions in the game. Clearly, as predictability goes down, so too does self-control.

As seen in the experiment, when put into a situation where the consequences of our actions are difficult to see due to their unpredictable nature, we would benefit greatly by simply recording our own choices and the outcomes they led to. The presence of feedback in the experiment almost negated the negative effects unpredictability had on self-control.

A dieter might have success by keeping an accurate record of daily dieting habits as well as a detailed record of the history of his/her weight. As in the experiment, if a dieter were to create a journal with entries every day recording whether their diet had been followed or not on the previous day and whether their weight had gone up or down since the previous day, after a while, the prospective dieter would be able to create feedback as in the experiment, “In the 42 days since I started dieting I followed my diet 31 times and failed follow my diet 11 times. When following my diet, my weight went down 26 times and up 5 times the next day. When I failed to follow my diet, my weight went down 3 times and up 8 times.” Such a record would surely allow a dieter to understand the probabilistic nature of weight loss.

References

Brown, J. C. (2006). The effects of behavioral and outcome feedback on prudent decision-making under conditions of present and future uncertainty. judgment and Decision Making, l(l), 76-85.

Brown, J.C. & Lovett, M. C. (2001). The effects of reducing information on a modified prisoner’s dilemma game. Proceedings of the Twenty-Third Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. 134-139.

Brown, J. C. & Rachlin, H. (1999). Self-control and social cooperation. Behavioural Processes, 47(2), 65-72.

Rachlin, H. (1991). Introduction to Modern Behaviorism (3rd ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Rachlin, H. (2000). The Science of Self Control. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.