9.4 Culture & Morality

Culture & Psychology

Universal Morality

Some of the most important and fundamental moral principles seem to be universally held by all people in all cultures and do not change over time. It has been found that starting at about age 10, children in most cultures come to a belief about harm-based morality—that harming others, either physically or by violating their rights, is wrong (Helwig & Turiel, 2002). Some research suggests that morality development begins much earlier in human development. Hamlin and colleagues used a puppet morality play in an experiment with infants and toddlers that found children preferred people who help others reach a goal (prosocial behaviors) and avoided people who were harmful, or who get in the way of others reaching a goal. As early as 3 months age, humans are evaluating the behaviors of others and assigning a positive value to helpful, cooperative behaviors (Hamlin et al., 2007; Hamlin & Wynn, 2011) and negative values to harmful or selfish behaviors. These fundamental and universal principles of morality include individual rights, freedom, equality, autonomy and cooperation.

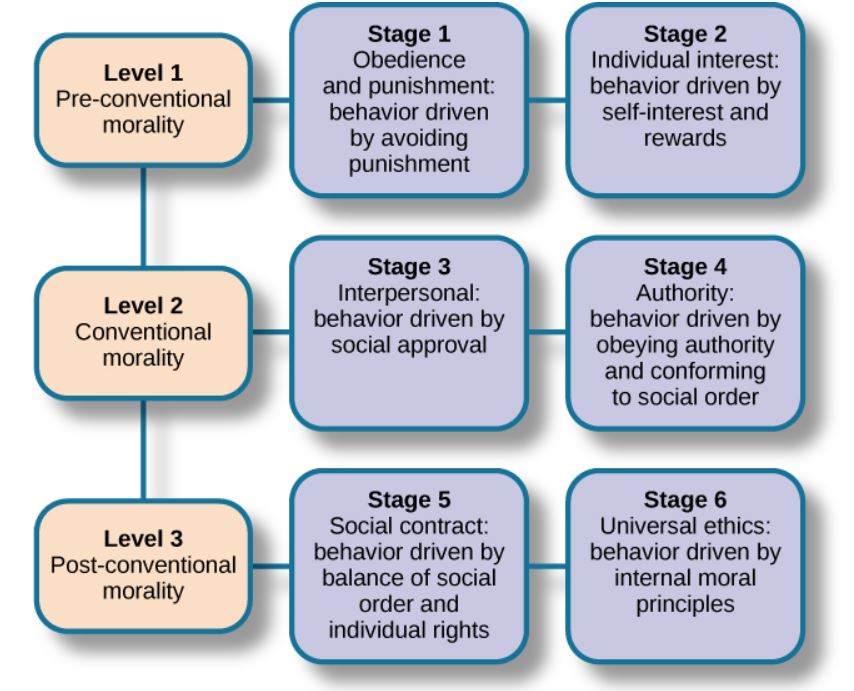

The theory that has the most cross-cultural empirical support is Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development, a cognitive development theory inspired by the work of Piaget. Moral development refers to the changes in moral beliefs as a person grows older and gains maturity.

According to Kohlberg’s theory, morality is based on the concept of equality and reciprocity of helping that can be predicted at certain ages. To develop this theory, Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to people of all ages; however, they were all White, males from the United States. One of Kohlberg’s best-known moral dilemmas is commonly known as the Heinz dilemma and participants were asked to decide what Heinz should do.

In Europe, a woman was near death from a special kind of cancer. There was one drug that the doctor’s thought might save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging ten times what the drug cost to make. He paid $200 for the radium and charged $2000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick woman’s husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about $1000, which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to see it cheaper or let him pay later. The druggist said, “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” So, Heinz got desperate and broke into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. Should the husband have done that? (Kohlberg, 1969, p. 379).

After presenting this and other moral dilemmas, Kohlberg reviewed people’s responses. Kohlberg was not interested in whether participants answered yes or no to the dilemma but rather he was interested in the reasoning behind their answer. Depending on the rationale, Kohlberg placed people into different stages of moral reasoning. Kohlberg identified three main levels of moral reasoning:

- Pre-conventional

- Conventional

- Post-conventional

Each level is associated with increasingly complex stages of moral and cognitive development. According to Kohlberg, an individual progresses from the capacity for pre-conventional morality (before age 9) to the capacity for conventional morality (early adolescence), and toward attaining post-conventional morality (once formal operational thought is attained), which only a few fully achieve. Kohlberg placed responses that reflected the reasoning that Heinz should steal the drug because his wife’s life is more important than the pharmacist making money in the highest stage. The value of a human life overrides the pharmacist’s greed. It is important to realize that even those people who have the most sophisticated, post-conventional reasons for some choices may make other choices to avoid getting into trouble (e.g., pre-conventional reasons).

Social Fairness

An essential part of morality involves determining what is considered “right” or “fair” in social interactions. As humans, we want things to be fair, we try to be fair ourselves, and we react negatively when we see things that are unfair. There is cultural variation regarding fairness because we determine what is or is not fair by relying on another set of social norms; the beliefs about how people should be treated fairly (Tyler & Lind, 2001; Tyler & Smith, 1998).

Most of us are familiar with the concept of equality, which suggests that everyone is treated the same and provided the same resources to succeed. For example, a health clinic in a small village can be open to everyone, but some villagers may lack the means to get to the village, or may not be able to afford medication. In this scenario, equality of health services has created a disparity of care – is that fair?

Another example that most of you are familiar with is applying for a job online. Most organizations, regardless of size almost exclusively use online recruitment and application processes which provides one system that everyone can use to apply for a job. One system and one platform that is the same for everyone – that’s equality, right? Except that the online application process may not be compatible with screen readers for the visually impaired and blind or the hiring algorithm may exclude you because of that D you earned in math. An underlying assumption of equality is that everyone starts in the same place and equally benefits from the same supports, which may or may not be the case.

Equity means ensuring that resources are equally distributed based on needs (Omrani-Khoo et al., 2013). Equity requires accounting for historical and current inequalities among groups of people who have been marginalized, excluded or experienced institutional discrimination. In this way, the concept of fairness is then based on the social and historical context. In our example about the clinic, health care workers might provide mobile care to reach villagers who cannot come to the clinic. They might also dispense medication on a sliding scale of payment so poor patients can get the treatment they need. When applying for a job, alternative applications and formats can be available for persons with disabilities when applying for jobs. The underlying assumption of equity is that everyone starts from a different place and receives the specific support and accommodations needed to produce fairness.

Equality and equity are separate constructs and sameness does not always translate into fairness, particularly across cultures. Justice, refers to the legal or philosophical perspective through which fairness is administered for the distribution of wealth, opportunities for personal activity, and social privileges. Current social justice efforts emphasize removing obstacles and underlying systemic barriers so that inequity is addressed and everyone receives equal access and resources. In the online application example, employers could ensure that their online platform is compatible with screen readers, videos have closed captions, fonts, colors and contrast can be adjusted to facilitate the process for individuals of all abilities.

One type of social fairness, known as distributive justice, refers to our judgments and perceptions about whether and how available rewards (resources) and costs are shared by (distributed across) group members. For example, if two people work equally hard on a project, they should get the same grade on it but if one works harder than the other, then the more hardworking partner should get a better grade. Distributive fairness is based on our perceptions of equity and is shaped by cultural norms.

Berman and colleagues (1984) presented American and Indian participants with a scenario about how to distribute a company bonus to employees. Findings revealed that American workers distributed the bonus based on equity norms (individual contributions to the company); whereas, the Indian workers distributed the bonus along need-based norms.

[Image by krzyboy2o Children Sharing a Milkshake CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Children_sharing_a_milkshake.jpg]

Recent research found that when presented with an uneven number of items, children tend to throw one item away rather than share the item unequally between two people they did not know. Paulus (2015) conducted a cross-cultural study to determine whether inequality aversion (e.g., throwing away rather than unequally sharing) is a universal concept. Results revealed that 6-7-year-old children in South Africa and the United States were more likely to throw out a resource rather than distribute it unequally. We might think of this as ‘better to be fair’. Ugandan children were more likely to distribute the resource even if it was unequally distributed. We might think of this as ‘wrong to waste’. These results challenge inequality aversion as a universal and suggests that there are cross-cultural differences in how children’s fairness-related decision making develops.

Cultural Considerations of Kohlberg’s Theory

There is cross-cultural support for Kohlberg’s theory of moral development (Gibbs, et al., 2007; Snarey, 1985). It appears that people progress through the stages in the same order; however, individuals in different cultures seem to do so at different rates. Some researchers question the universality of all stages in all cultures. For example, the highest level of Kohlberg’s theory posits that individual principles should override social or cultural tradition and laws. Inherent in this view is a hierarchy which is inconsistent with collectivist cultural values. Additionally, Kohlberg’s theory does not consider relationships, affiliation or justice. As you might expect, his work has been criticized for using only White, males from the Midwestern United States and for his assertion that women seem to be deficient in their moral reasoning abilities when compared to men.

Carol Gilligan (1982) criticized Kohlberg’s theory and instead proposed that males and females reason differently about morality. She argued that girls and women focus more on staying connected and maintaining interpersonal relationships, whereas boys and men emphasize justice and individual rights. She labelled these the Morality of Caring and the Morality of Justice. Additionally, Shaffer and colleagues (2002) argued that Kohlberg’s theory neglects to consider the central role that emotion plays in morality. Given that emotions play a critical role in influencing our thoughts and motivating our actions, it seems critical that emotion be part of the model. Other models of morality have emerged to address these limitations and the most widely discussed within cultural psychology is the Three Ethic Model of Morality.

Cultural Alternatives to Moral Development

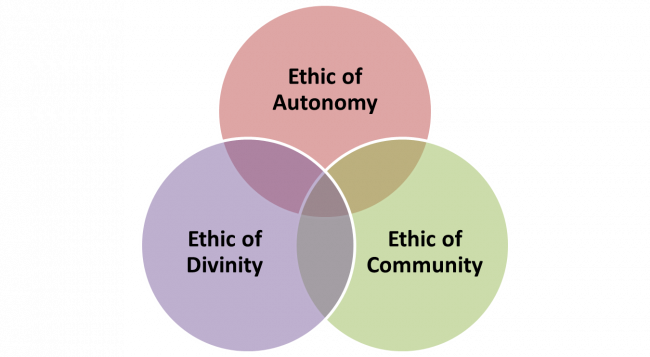

Shweder and colleagues (1984; 1987) proposed a new model of ethics that address concepts consistent with the moral belief systems of many cultures and not restricted to Western values of autonomy and individual rights. Cultural anthropologists and some cultural psychologists argue that morality is not always universal but rather unique cultural experiences shape views of fairness, morality and justice. Using fieldwork in India with adults and children of the Brahman class (sometimes referred to as the untouchables), Shweder and colleagues found that Western morality of harm avoidance and individual rights was insufficient and neglected other cultural definitions of morality and so created the Three Ethic Model of Morality:

- Ethic of Autonomy most closely aligns with Kohlberg’s theory of morality with an emphasis on harm, rights, justice and personal autonomy. Principles of fairness emerge very early in development, prior to socialization influences (Wainryb, 2006; Sunbar, 2018). Children in diverse cultures such as the United States, India, China, Turkey, and Brazil share a pervasive view about upholding fairness and the wrongfulness of inflicting harm on others (Wainryb, 2006).

- Ethic of Community refers to being part of an organized community and recognizing that you have a social role within that community. This ethnic encompasses relationships, social obligations, duty, hierarchy and interdependence on community members.

- Ethic of Divinity addresses our relationship with a higher power, divinity, the sacred, godliness and the order of the natural world.

Cross-cultural research has found support for the Three Ethic Model of Morality and the role of culture and moral judgment across different populations (Haidt, Koller & Dias, 1993). Haidt and colleagues found that children and adults in the United States and individuals with high socioeconomic status (SES) provided responses more consistent with ethics of autonomy than community or divinity. Samples of children and adults from Brazil had broader definitions of morality that extended beyond harm and autonomy.

Cross-cultural research has found support for the Three Ethic Model of Morality and the role of culture and moral judgment across different populations (Haidt, Koller & Dias, 1993). Haidt and colleagues found that children and adults in the United States and individuals with high socioeconomic status (SES) provided responses more consistent with ethics of autonomy than community or divinity. Samples of children and adults from Brazil had broader definitions of morality that extended beyond harm and autonomy.

Intracultural research within the United States has found that political liberals and conservatives emphasize different moral foundations with regard to harm and fairness (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009). The moral foundations of the groups were the same (no real moral differences between the political groups) but the degree of endorsement for some morals was significantly different for political conservatives and liberals.