7.2 Enculturation

Enculturation

L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero

It is important to understand that culture is learned. People aren’t born using chopsticks or being good at soccer simply because they have a genetic predisposition for it. They learn to excel at these activities because they are born in countries like Argentina, where playing soccer is an important part of daily life, or in countries like Taiwan, where chopsticks are the primary eating utensils.

So, how are such cultural behaviors learned? It turns out that cultural skills and knowledge are learned in much the same way a person might learn to do algebra or knit. They are acquired through a combination of explicit teaching and implicit learning— by observing and copying.

Cultural teaching can take many forms. As discussed in Chapter 2, social learning occurs when behavior is taught or modeled to another. In child development, cultural shaping begins with caretakers and their young. Caregivers teach kids, both directly and by example, about how to behave and how the world works. They encourage children to be polite, reminding them, for instance, to say “Thank you.” They teach kids how to dress in a way that is appropriate for the culture. They introduce children to religious beliefs and the rituals that go with them. They even teach children how to think and feel! This uniquely human form of learning, where the cultural tools for success are passed from one generation to another, is what is known as enculturation.

Enculturation and the Brain

The topic of genetic influences versus environmental influences on human development is often referred to as the, “nature-nurture debate.” It would be satisfying to be able to say that nature–nurture studies have given us conclusive and complete evidence about where traits come from, with some traits clearly resulting from genetics and others almost entirely from environmental factors, such as childrearing practices and personal will; but that is not the case. Instead, everything has turned out to have some footing in genetics. The message is clear: You can’t leave genes out of the equation. Keep in mind that no behavioral traits are completely inherited, so you can’t leave the environment out altogether.

Cultural neuroscience is a field of research that focuses on the interrelation between a human’s cultural environment and neurobiological systems. Our brain works to interact and, in essence, learn from our environment beginning from the moment of conception. Neural patterns form, are shaped and reshaped, continually through a process of feedback and interaction with our world. Each person has periods of brain development (typically in early childhood) where this neurological wiring is acquired smoother and faster than at any other point of time in development.

Research by Kitayama and Uskul (2011), along with others, has found evidence to support that windows for pathway wiring in the brain also occur for enculturation. In other words, cultural neuroscience investigates the way our brain is wired for cultural practices, values, and traditions through our early childhood experiences. These pathways form naturally in the brain and are then reinforced through feedback and repetition. Kitayama and Salvador (2017) write that, “culture is embrained.”

Ecological Systems Theory

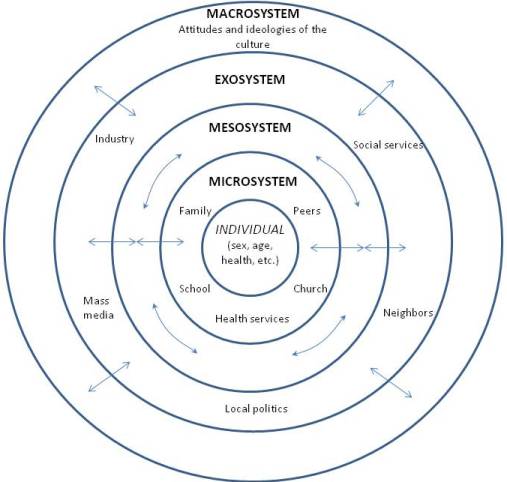

Contextual characteristics, such as the neighborhood, school, and social networks, also affect enculturation, even though these settings don’t always include both the child and the parent (Brofenbrenner, 1989). For example, Latina mothers who perceived the neighborhood as more dangerous showed less warmth with their children, perhaps because of the greater stress associated with living in a threatening environment (Gonzales et al., 2011). Urie Bronfenbrenner was a Russian-born American developmental psychologist who is known for his ecological systems theory of child development. His scientific work and his assistance to the United States government helped in the formation of the Head Start program in 1965.

Bronfenbrenner’s research and his theory was key in changing the perspective of developmental psychology by calling attention to the large number of environmental and societal influences on child development. Bronfenbrenner saw the process of human development as being shaped by the interaction between an individual and his or her environment. The specific path of development was a result of the influences of a person’s surroundings, such as their parents, friends, school, work, culture, and so on.

According to Melvin L. Kohn, a sociologist from Johns Hopkins University, Bronfenbrenner was critical in making social scientists realize that, “…interpersonal relationships, even [at] the smallest level of the parent-child relationship, did not exist in a social vacuum but were embedded in the larger social structures of community, society, economics and politics.”

Peer and Sibling Relationships

Parent-child relationships are not the only significant relationships in a child’s life. Peer relationships are also important. Social interaction with another child who is similar in age, skills, and knowledge provokes the development of many social skills that are valuable for the rest of life (Bukowski, Buhrmester, & Underwood, 2011). In peer relationships, children learn how to initiate and maintain social interactions with other children. They learn skills for managing conflict, such as turn-taking, compromise, and bargaining. Play also involves the mutual, sometimes complex, coordination of goals, actions, and understanding. For example, as infants, children get their first encounter with sharing (of each other’s toys); during pretend play as preschoolers they create narratives together, choose roles, and collaborate to act out their stories; and in primary school, they may join a sports team, learning to work together and support each other emotionally and strategically toward a common goal. Through these experiences, children develop friendships that provide additional sources of security and support to those provided by their parents.

Peer relationships can be challenging as well as supportive (Rubin, Coplan, Chen, Bowker, & McDonald, 2011). Being accepted by other children is an important source of affirmation and self-esteem, but peer rejection can foreshadow later behavior problems (especially when children are rejected due to aggressive behavior). With increasing age, children confront the challenges of bullying, peer victimization, and managing conformity pressures. Social comparison with peers is an important means by which children evaluate their skills, knowledge, and personal qualities, but it may cause them to feel that they do not measure up well against others. Also, with the approach of adolescence, peer relationships become focused on psychological intimacy, involving personal disclosure, vulnerability, and loyalty (or its betrayal)—which significantly affects a child’s outlook on the world. Each of these aspects of peer relationships requires developing very different social and emotional skills than those that emerge in parent- child relationships. They also illustrate the many ways that peer relationships influence the growth of personality and self-concept.

Education

As previously stated, caretakers serve the role of being primary enculturation agents of their young in any given society. If parents serve as the #1 enculturation agent, education would likely be the second most important source of enculturation for any child.

Education is the process of facilitating learning, or the acquisition of knowledge, skills, values, beliefs, and habits. Educational methods include storytelling, discussion, teaching, training, and directed research. Education frequently takes place under the guidance of educators, but learners may also educate themselves. Education can take place in formal or informal settings and any experience that has a formative effect on the way one thinks, feels, or acts may be considered educational.

Culture, education, and society are all interconnected concepts that work to enculturate a child. Education models are based on the ideals and principles of society, and then its educated citizens go on to become influencers of that society’s culture. Researchers Markus and Kitayama (2010) refer to the systemic influence of culture and self as mutual constitution, and point out that individuals are simultaneously being shaped by culture while also influencing it. Regardless of the method of education, schooling serves as both a reflection of the priorities and values of that society, while also enculturating its young to contribute to that culture. For example, core American values of competition, choice, and independence can be seen in the way we structure our formal education system. Parents and students often expect to play a role in choosing curriculum, classes and competition for academic and athletic status is expected within schools. Similarly, in the United States the government dictates larger educational goals and resources, while state and local districts pass mandates based on the democratic wishes of larger society. In contrast to Westernized systems of education, many East Asian education models are based on uniform standards of academic rigor, student conformity, and respect for authority.

Think back to an emotional event you experienced as a child. How did your parents react to you? Did your parents get frustrated or criticize you? Did they act patiently and provide support and guidance? Did your parents provide lots of rules for you or let you make decisions on your own? Why do you think your parents behaved the way they did? Enculturation agents are individuals and institutions that serve a role in shaping individual adaptations to a specific culture to better ensure growth and effectiveness.

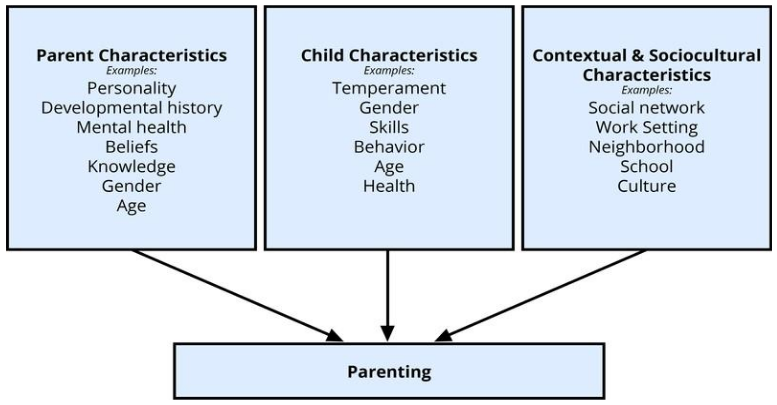

Parents and caretakers are a primary enculturation agent for their young. Psychologists have attempted to answer questions about the influences on parents and understand why parents behave the way they do. Because parents are critical to a child’s development, a great deal of research has been focused on the impact that parents have on children. Parenting is a complex process in which parents and children influence one another. There are many reasons that parents behave the way they do.

The multiple influences on parenting are still being explored. Both caretakers and their children bring unique personality traits, characteristics, and habits to the parent-child dynamic that ultimately impacts the child’s development. Culture also influences parenting behaviors in fundamental ways. Although promoting the development of skills necessary to function effectively in one’s community is a universal goal of parenting, the specific skills necessary vary widely from culture to culture. Parents have different goals for their children that partially depend on their culture (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008).

Differences in caretaking reflect differences in parenting goals, values, resources, and experiences. As previously stated, culture is learned. Regardless of the specific choices parents make, it can be said that caretakers play a pivotal role in exposing a child to early cultural learning. In fact, many researchers believe that parents/caretakers serve as the single, most important enculturation agent in any child’s life.

While some parenting priorities are culturally universal (parents are expected to play a role in nurturing and raising their young), many more childrearing values and habits are culture-specific. Culture-specific influences on caretaking choices can be subtle or overt, and promote a narrative of what parents “ought” to do in order to successfully raise their children. For example, American parents are encouraged to enculturate a sense of independence and assertiveness in children, while Japanese parents prioritize self-control, emotional maturity, and interdependence (Bornstein, 2012). Undoubtedly, every society places expectations on caretakers as enculturation agents to raise their young in ways that promote culture-specific goals and expectations. This chapter will focus on four areas of child development:

- Temperament

- Attachment

- Parenting Styles

- Cognition