1.4 Defining Culture

L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero

We have spent a lot of time talking about culture without really defining it and to complicate matters more, there are many definitions of culture and it is used in different ways by different people. When someone says, “My company has a competitive culture,” does it mean the same thing as when another person says, “I’m taking my children to the museum so they can get some culture”? For purposes of this module we are going to define culture as patterns of learned and shared behavior that are cumulative and transmitted across generations.

Patterns: There are systematic and predictable ways of behavior or thinking across members of a culture. Patterns emerge from adapting, sharing, and storing cultural information. Patterns can be both similar and different across cultures. For example, in both Canada and India it is considered polite to bring a small gift to a host’s home. In Canada, it is more common to bring a bottle of wine and for the gift to be opened right away. In India, by contrast, it is more common to bring sweets, and often the gift is set aside to be opened later.

Sharing: Culture is the product of people sharing with one another. Humans cooperate and share knowledge and skills with other members of their networks. The ways they share, and the content of what they share, helps make up culture. Older adults, for instance, remember a time when long-distance friendships were maintained through letters that arrived in the mail every few months. Contemporary youth culture accomplishes the same goal through the use of instant text messages on smartphones.

Learned: Behaviors, values, norms are acquired through a process known as enculturation that begins with parents and caregivers, because they are the primary influence on young children. Caregivers teach kids, both directly and by example, about how to behave and how the world works. They encourage children to be polite, reminding them, for instance, to say “Thank you.” They teach kids how to dress in a way that is appropriate for the culture.

Culture teaches us what behaviors and emotions are appropriate or expected in different situations. In some societies, it is considered appropriate to conceal anger. Instead of expressing their feelings outright, people purse their lips, furrow their brows, and say little. In other cultures, however, it is appropriate to express anger. In these places, people are more likely to bare their teeth, furrow their brows, point or gesture, and yell (Matsumoto, Yoo, & Chung, 2010).

Members of a culture also engage in rituals which are used to teach people what is important. For example, young people who are interested in becoming Buddhist monks often have to endure rituals that help them shed feelings of specialness or superiority—feelings that run counter to Buddhist doctrine. To do this, they might be required to wash their teacher’s feet, scrub toilets, or perform other menial tasks. Similarly, many Jewish adolescents go through the process of bar and bat mitzvah. This is a ceremonial reading from scripture that requires the study of Hebrew and, when completed, signals that the youth is ready for full participation in public worship. These examples help to illustrate the concept of enculturation.

Cumulative: Cultural knowledge is information that is “stored” and then the learning grows across generations. We understand more about the world today than we did 200 years ago, but that doesn’t mean the culture from long ago has been erased. For instance, members of the Haida culture, a First Nations people in British Columbia, Canada are able to profit from both ancient and modern experiences. They might employ traditional fishing practices and wisdom stories while also using modern technologies and services.

Transmission: Passing of new knowledge and traditions of culture from one generation to the next, as well as across other cultures is cultural transmission. In everyday life, the most common way cultural norms are transmitted is within each individuals’ home life. Each family has its own, distinct culture under the big picture of each given society and/or nation. With every family, there are traditions that are kept alive. The way each family acts and communicates with others and an overall view of life are passed down. Parents teach their kids every day how to behave and act by their actions alone. Outside of the family, culture can be transmitted at various social institutions like places of worship, schools, even shopping centers are places where enculturation happens and is transmitted.

Understanding culture as a learned pattern of thoughts and behaviors is interesting for several reasons. First, it highlights the ways groups can come into conflict with one another. Members of different cultures simply learn different ways of behaving. Teenagers today interact with technologies, like a smartphone, using a different set of rules than people who are in their 40s, 50s, or 60s. Older adults might find texting in the middle of a face-to-face conversation rude while younger people often do not.

These differences can sometimes become politicized and a source of tension between groups. One example of this is Muslim women who wear a hijab, or headscarf. Non-Muslims do not follow this practice, so occasional misunderstandings arise about the appropriateness of the tradition. Second, understanding that culture is learned is important because it means that people can adopt an appreciation of patterns of behavior that are different than their own. Finally, understanding that culture is learned can be helpful in developing self-awareness. For instance, people from the United States might not even be aware of the fact that their attitudes about public nudity are influenced by their cultural learning. While women often go topless on beaches in Europe and women living a traditional tribal existence in places like the South Pacific also go topless, it is illegal for women in some of the United States to do so.

These cultural norms for modesty that are reflected in government laws and policies also enter the discourse on social issues such as the appropriateness of breastfeeding in public. Understanding that your preferences are, in many cases, the products of cultural learning might empower you to revise them if doing so will lead to a better life for you or others.

Humans use culture to adapt and transform the world they live in and you should think of the word culture as a conceptual tool rather than as a uniform, static definition. Culture changes through interactions with individuals, media, and technology, just to name a few. Culture generally changes for one of two reasons: selective transmission or to meet changing needs. This means that when a village or culture is met with new challenges, for example, a loss of a food source, they must change the way they live. It could also include forced relocation from ancestral domains due to external or internal forces. For example, in the United States tens of thousands Native Americans were forced to migrate from their ancestral lands to reservations established by the United States government so it could acquire lands rich with natural resources. The forced migration resulted in death, disease and many cultural changes for the Native Americans as they adjusted to new ecology and way of life.

Hofstede’s cultural values provide a framework that describes the effects of culture on the values of its members, and how these values relate to behavior. Hofstede’s work is a major resource in fields like cross-cultural psychology, international management, and cross-cultural communication.

Hofstede conducted a large survey (1967-1973) that examined value differences across the divisions of IBM, a multinational corporation. Data were collected from 117,000 employees from 50 countries across 3 regions. Using factor analysis, a statistical method, Hofstede initially identified four value dimensions (Individualist/Collectivist, Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, and Masculinity/Femininity). Additional research that used a Chinese developed tool identified a fifth dimension: Long Term/Short Term orientation (Bond, 1991) and a replication, conducted across 93 separate countries, confirmed the existence of the five dimensions and identified a sixth known as Indulgence/Restraint (Minkov, 2010). The five values are discussed in detail below.

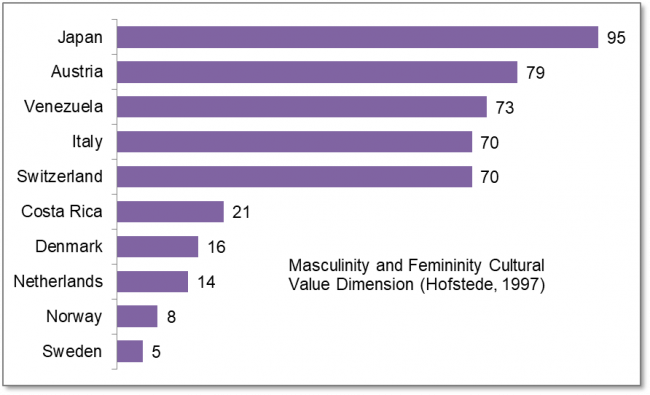

Masculinity and Femininity (task orientation/person orientation) refers to the distribution of emotional roles between the genders. Masculine cultures value competitiveness, assertiveness, material success, ambition, and power. Female cultures place more value on relationships, quality of life and greater concern for marginalized groups (e.g., homeless, persons with disabilities, refugees). In masculine cultures differences in gender roles are very dramatic and much less fluid than those in feminine cultures where women and men have the same values that emphasize modesty and caring. Masculine cultures are also more likely to have strong opinions about what constitutes men’s work versus women’s work, while societies low in masculinity permit much greater overlap in social and work roles of men and women.

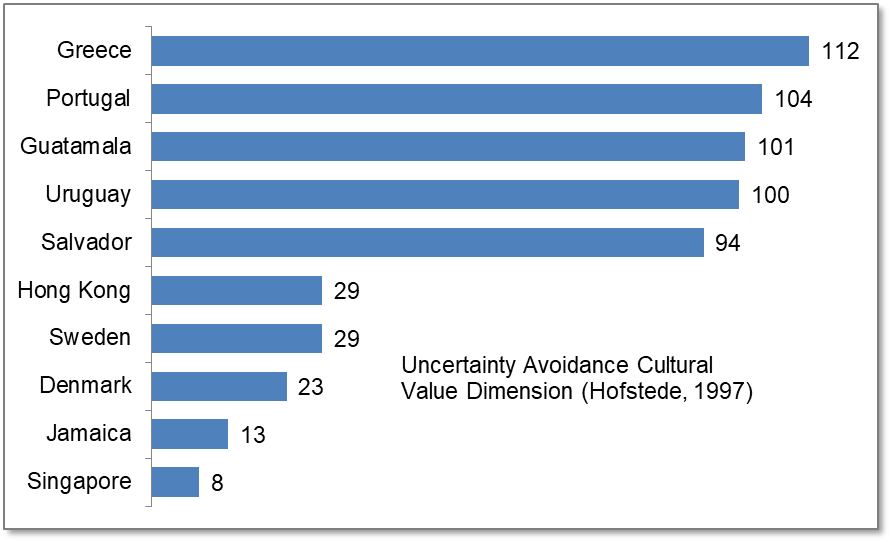

Uncertainty Avoidance (UA) addresses a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. It reflects the extent to which members of a society attempt to cope with anxiety by minimizing uncertainty. Another, more simplified, way to think about UA is how threatening change is to a culture. People in cultures with high UA tend to be more emotional, try to minimize the unknown and unusual circumstances and proceed with carefully planned steps and rules, laws and regulations. Low UA cultures accept and feel comfortable in unstructured situations or changeable environments and try to have as few rules as possible. People in these cultures tend to be more tolerant of change. Students from countries with low uncertainty avoidance don’t mind it when a teacher says, “I don’t know.”

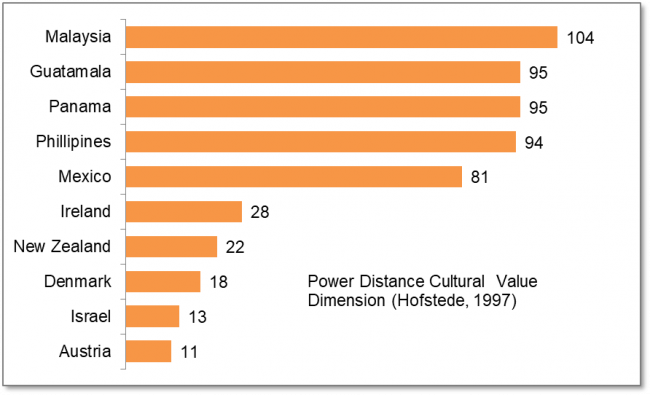

Power Distance (strength of social hierarchy) refers to the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions (like a family) accept and expect that power is distributed unequally. There is a certain degree of inequality in all societies, notes Hofstede; however, there is relatively more equality in some societies than in others. Individuals in societies that exhibit a high degree of power distance accept hierarchies to which everyone has a place without the need for justification. Societies with low power distance seek to have an equal distribution of power. Cultures that endorse low power distance expect and accept relations that are more consultative or democratic – we call this egalitarian.

Countries with lower PDI values tend to be more egalitarian. For instance, there is more equality between parents and children with parents more likely to accept it if children argue with them, or “talk back” to use a common expression. In the workplace, bosses are more likely to ask employees for input, and in fact, subordinates expect to be consulted. On the other hand, in countries with high power distance, parents expect children to obey without questioning. People of higher status may expect obvious displays of respect from subordinates. In the workplace, superiors and subordinates are not likely to see each other as equals, and it is assumed that bosses will make decisions without consulting employees. In general, status is more important in high power distance countries.

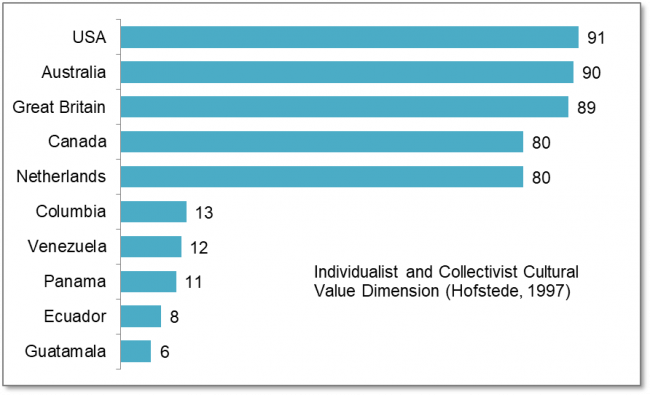

Individualist and Collectivism refers to the degree to which individuals are integrated into groups. Individualistic societies stress personal achievement and individual rights, focus on personal needs and those of immediate family. In individualistic societies, people choose their own affiliations and groups and move between different groups. On the other hand, collectivistic societies put more emphasis on the importance of relationships and loyalty. Individuals in collectivist societies belong to fewer groups and they are defined more by their membership in particular groups. Communication is more direct in individualistic societies but more indirect in collectivistic societies.

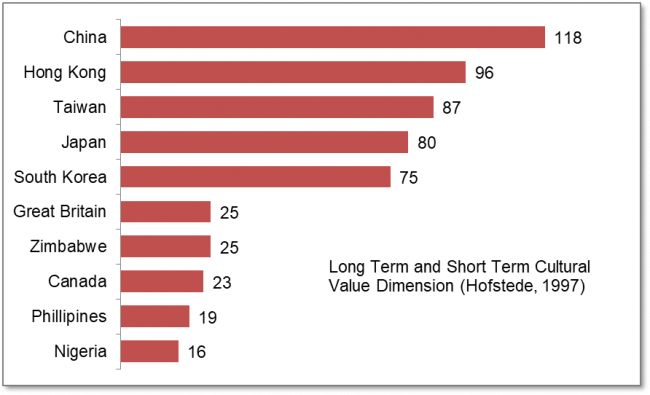

Long Term (LT) and Short Term (ST) describes a society’s time horizon; the degree to which cultures encourage delaying gratification or material, social, emotional needs of the members: LT places more importance on the future, pragmatic values, oriented toward rewards like persistence, thrift, saving, and capacity for adaptation. Short term values are related to the past and the present (not future) with emphasis on immediate needs, quick results, and unrestrained spending often in response to social or ecological pressure.

Considerations and Criticisms

The cultural value dimensions identified by Hofstede are useful ways to think about culture and to study cultural psychology; however, Hofstede’s theory has also been seriously questioned. Most of the criticism has been directed at the methodology of the study beginning with the original instrument. The questionnaire was not originally designed to measure culture but rather workplace satisfaction (Orr & Hauser, 2008) and many of the conclusions are based on a small number of responses (McSweeney, 2002). Although 117,000 questionnaires were administered, the results from 40 countries were used and only six countries had more than 1000 respondents. Critics also question the representativeness of the original sample.

The study was conducted using employees of a multinational corporation (IBM) who were highly educated, mostly male, who performed what we call ‘white collar’ work (McSweeney, 2002). Hofstede’s theory has also been criticized for promoting a largely static view of culture (Hamden-Turner & Trompenaars, 1997; Orr and Hauser, 2008) that does not respond to changes or influences of other cultures. It is hard to deny that the world has changed in dramatic ways since Hofstede’s research began.

Material and nonmaterial aspects of culture can vary subtly from region to region. As people travel, moving from different regions to entirely different parts of the world, certain material and nonmaterial aspects of culture become dramatically unfamiliar. As we interact with cultures other than our own, we become more aware of our own culture, which might otherwise be invisible to us, and to the differences and commonalities between our culture and others.