13.3 Cognition

L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero

Attention is the behavioral and cognitive process of selectively concentrating on one thing in our environment while ignoring other distractions. Attention is a limited resource. This means that your brain can only devote attention to a limited number of stimuli (things in the environment). Despite what you may believe, we are terrible multi-taskers. Research shows that when multitasking, people make more mistakes or perform their tasks more slowly. Each task increases cognitive load (the amount of information our brain has to process) and our attention must be divided among all of the tasks to perform them. This is why it takes more time to finish something when we are multitasking.

Many aspects of attention have been studied in the field of psychology. In some respects, we define different types of attention by the nature of the task used to study it. For example, a crucial issue in World War II was how long an individual could remain highly alert and accurate while watching a radar screen for enemy planes, and this problem led psychologists to study how attention works under such conditions. Research results found that when watching for a rare event, it is easy to allow concentration to lag. This continues to be a challenge today for TSA agents, charged with looking at images of the contents of your carry-on luggage in search of knives, guns, or shampoo bottles larger than 3 oz.

Culture can also influence and shape how we attend to the world around us. Masuda and Nisbett (2001) asked American and Japanese students to describe what they saw in images like the one shown below. They found that while both groups talked about the most salient objects (the fish, which were brightly colored and swimming around), the Japanese students also tended to talk and remember more about the images in the background (they remembered the frog and the plants as well as the fish).

North Americans and Western Europeans in these types of studies were more likely to pay attention to salient and central parts of the pictures, while Japanese, Chinese, and South Koreans were more likely to consider the context as a whole. The researchers described this as holistic perception and analytic perception.

Holistic Perception: A pattern or perception characterized by processing information as a whole. This pattern makes it more likely to pay attention to relationships among all elements. Holistic perception promotes holistic cognition: a tendency to understand the gist, the big idea, or the general meaning. Eastern medicine is traditionally holistic; it emphasizes health in general terms as the result of the connection and balance between mind, body, and spirit.

Analytic Perception: A pattern of perception characterized by processing information as a sum of the parts. Analytic perception promotes analytic thinking: a tendency to understand the parts and details of a system. This pattern makes it more likely to pay attention and remember salient, central, and individual elements. Western medicine is traditionally analytic; it emphasizes specialized subdisciplines and it focuses on individual symptoms and body parts.

The way we represent the world influences the degree of success we experience in our lives. For example, if we represent yellow traffic lights as the time to hit the accelerator, then the world might give us tickets, scares, or accidents. If we represent our diet as a way to maximize refined sugar intake, then we might wind up experiencing heart disease. Mental representations and intelligence go hand in hand. Some mental representations are more intelligent, because they are more adaptive and support outcomes such as well-being, safety, and success. In this section we are going to cover other elements of thinking like categorization, memory, and intelligence and how culture shapes these processes.

Categories and Concepts

The information we sense and perceive is continuously organized and reorganized into concepts that belong to categories. Most concepts cannot be strictly defined but are organized around the best examples or prototypes, which have the properties most common in the category or might be considered the ideal example of a category.

Concepts are at the core of intelligent behavior. We expect people to be able to know what to do in new situations and when confronting new objects. If you go into a new classroom and see chairs, a blackboard, a projector, and a screen, you know what these things are and how they will be used. You’ll sit on one of the chairs and expect the instructor to write on the blackboard or project something onto the screen. You’ll do this even if you have never seen any of these particular objects before, because you have concepts of classrooms, chairs, projectors, and so forth that tell you what they are and what you’re supposed to do with them.

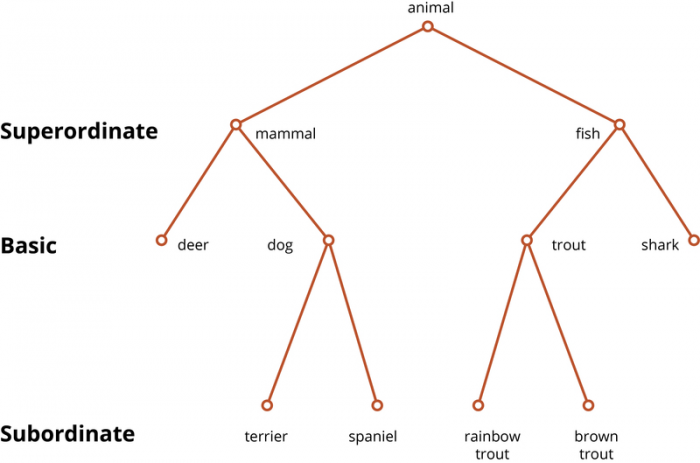

Objects fall into many different categories, but there is usually a hierarchy to help us organize our mental representations.

- A concept at the superordinate level of categories is at the top of a taxonomy and it has a high degree of generality (e.g., animal, fruit).

- A concept at the basic level categories is found at the generic level which contains the most salient differences (e.g., dog, apple).

- A concept at the subordinate level of categories is specific and has little generality (e.g., Labrador retriever, Gala).

Brown (1958) noted that children use basic level categories when first learning language and superordinates are especially difficult for children to fully acquire. People are faster at identifying objects as members of basic-level categories (Rosch et al., 1976). Recent research suggests that there are different ways to learn and represent concepts and that they are accomplished by different neural systems. Using our earlier example of a classroom, if someone tells you a new fact about the projector, like it uses a halogen bulb, you are likely to extend this fact to other projectors you encounter. In short, concepts allow you to extend what you have learned about a limited number of objects to a potentially infinite set of events and possibilities.

Categorization and Culture

There are some universal categories like emotions, facial expressions, shape and color but culture can shape how we organize information. Chiu (1972) was the first to examine cultural differences in categorization using Chinese and American children. Participants were presented with three pictures (e.g., a tire, a car, and a bus), and were asked to group the two pictures they thought best belonged together. Participants were also asked to explain their choices (e.g., “Because they are both large”). Results showed that the Chinese children have a greater tendency to categorize by identifying relationships among the pictures but American children were more likely to categorize by identifying similarities among pictures.

Later research reported no cultural differences in categorization between Western and East Asian participants; however, among similarity categorizations the East Asian participants were more likely to make decisions on holistic aspects of the images and Western participants were more like to make decisions based on individual components of the images (Norenzayan, Smith, Jun Kim, and Nisbett, 2002). Cultural differences in categorizing were also found by Unworth, Sears and Pexman (2005) across three experiments; however, when the experiment task was timed there were differences in category selection. These results suggest that the nature (timed or untimed) of the categorization task determines the extent to which cultural differences are observed.

The results of these categorization studies seem to support the differences in thinking between individualist and collectivist cultures. Western cultures are more individualist and engage in more analytic thinking and East Asian cultures engage in more holistic thinking (Choi, Nisbett, & Smith, 1997; Masuda & Nisbett, 2001; Nisbett et al., 2001; Peng & Nisbett, 1999). You might remember from the earlier section that holistic thought is characterized by a focus on context and environmental factors so categorizing by relationships can be explained with referencing how objects relate to their environment. Analytic thought is characterized by the separation of an object from its context so categorizing by similarity means that objects can be separated into different groups. A major limitation with these studies is the emphasis on East Asian, specifically the use of Chinese participants and Western cultures. There have been no within culture replications using participants from other non-Asian collectivist cultures.

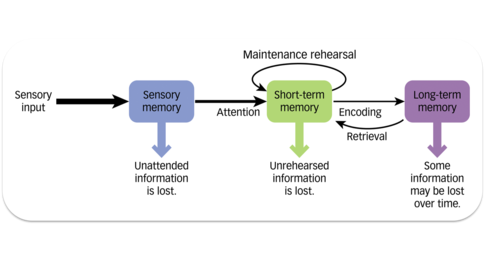

Memory is a single term that reflects a number of different abilities: holding information briefly while working with it (working memory), remembering episodes of one’s life and our general knowledge of facts of the world among other types. Memory involves three processes:

- Encoding information – attending to information and relating it to past learning

- Storing – maintaining information over time

- Retrieving – accessing the information when you need it

The information processing model of memory is a useful way to represent how information from the world is integrated with the knowledge networks of information that already exist in our minds.

Sensory Memory is the part of the memory system in which information is translated from physical energy into neural signals. This is part of the encoding process. We receive information from our environment and we must perceive it and attend to it before it can move to our working memory.

Short-Term Memory (working memory) is the part of the memory system in which information can be temporarily stored in the present state of awareness. This type of memory is limited to 7 items of capacity and 7 to 30 seconds of duration on average.

Long-Term Memory is the part of the memory system in which information can be permanently stored for an extended period of time. It has a large to unlimited capacity and a duration that may last from minutes to a lifetime.

Semantic Memory is the type of long-term memory about general facts, ideas, or concepts that are not associated with emotions and personal experience.

Episodic Memory is a type of long-term memory about events taking place at a specific time and place in a person’s life. This memory is contextualized (i.e., where, who, when, why) in relation to events and what they mean emotionally to an individual.

[Image by Educ320, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_modal_model.png CC BY-SA]

Memory failures can occur at any stage, leading to forgetting or to having false memories. The key to improving one’s memory is to improve processes of encoding and to use techniques that guarantee effective retrieval. Good encoding techniques include relating new information to what one already knows, forming mental images, and creating associations among information that needs to be remembered. The key to good retrieval is developing effective cues that will lead the person back to the encoded information. Classic mnemonic systems can greatly improve one’s memory abilities.

Memory and Culture

It should be obvious, after learning about episodic memory that many of our memories are personal and unique to us but cultural psychologists and researchers have found that the average age of first memories varies up to two years between different cultures. Researchers believe that enculturation and cultural values influence childhood memories. For example, the way parents and other adults discuss, or don’t discuss, the events in children’s lives influences the way the children will later remember those events.

Mullen (1994) found that Asian and Asian-American undergraduates’ memories, on average, happened six months later than the Caucasian students’ memories. These results were repeated in a sample of native Korean participants, only this time the differences were even larger. The difference between Caucasian participants and native Korean participants was almost 16 months. Hayne (2000) also found that Asian adults’ first memories were later than Caucasians’ but Maori adults’ (native population from New Zealand) memories reached even further back to around age three. These results do not mean that Caucasians or Maoris have better memories than Asians but rather people have the types of memories that they need to get along well in the world they inhabit – memories exist within cultural context. For example, Maori culture is focused on personal history and stories to a greater degree than American culture and Asian culture. Differences in memory could also be explained by the values of individualistic and collectivist cultures. Individualistic cultures tend to be independently oriented with an emphasis on standing out and being unique. Interpersonal harmony and making the group work is the emphasis of collectivist cultures and the way in which people connect to each other is less often through sharing memories of personal events. In some cultures, personal memory isn’t nearly as important as it is to people from individualistic cultures.

Social Cognitions

The culture that we live in has a significant impact on the way we think about and perceive our social worlds, so it is not surprising that people in different cultures would think about people and things somewhat differently. Social cognitions are the way we think about others, pay attention to social information, and use the information in our lives (consciously or unconsciously). In this section we will review several types of social cognitions including schemas, attributions, confirmation bias and the fundamental attribution error. We will also revisit analytic perception and holistic perception that we learned earlier in this chapter.

Schema

Through the process of cognitive development, we accumulate a lot of knowledge and this knowledge is stored in the form of schemas, which are knowledge representations that include information about a person, group, or situation. Because they represent our past experience, and because past experience is useful for prediction, our schemas influence our expectations about future events and people.

When a schema is activated it brings to mind other related information. This process is usually unconscious, or happens outside of our awareness. Through schema activation, judgments are formed based on internal assumptions (bias) in addition to information actually available in the environment. When a schema is more accessible it can be activated more quickly and used in a particular situation. For example, if there is one female in a group of seven males, female gender schemas may be more accessible and influence the group’s thinking and behavior toward the female group member. Watching a scary movie late at night might increase the accessibility of frightening schemas, increasing the likelihood that a person will perceive shadows and background noises as potential threats.

Once they have developed, schemas influence our subsequent learning, such that the new people and situations we encounter are interpreted and understood in terms of our existing knowledge (Piaget & Inhelder, 1962; Taylor & Crocker, 1981). When existing schemas change on the basis of new information, we call the process accommodation. In other cases, however, we engage in assimilation, a process in which our existing knowledge influences new conflicting information to better fit with our existing knowledge, thus reducing the likelihood of schema change. You may remember these concepts from Chapter 4 when we learned about Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.

Psychologists have become increasingly interested in the influence of culture on social cognition and schemas. Although people of all cultures use schemas to understand the world, the content of our schemas has been found to differ for individuals based on their cultural upbringing. For example, one study interviewed a Scottish settler and a Bantu herdsman from Swaziland and compared their schemas about cattle. Because cattle are essential to the lifestyle of the Bantu people, the Bantu herdsman’s schemas for cattle were far more extensive than the schemas of the Scottish settler. The Bantu herdsmen were able to distinguish his cattle from dozens of others, while the Scottish settler was not.

One outcome of assimilation that shapes our schema is confirmation bias, the tendency for people to seek out and favor information that confirms their expectations and beliefs, which in turn can further help to explain the often, self-fulfilling nature of our schemas. The confirmation bias has been shown to occur in many contexts and groups, although there is some evidence of cultural differences in its extent and prevalence. Kastenmuller and colleagues (2010), for instance, found that the bias was stronger among people with individualist (e.g., the United States, Canada, and Australia) versus collectivist (e.g., Japan, China, Taiwan, Korea, India among others) cultural backgrounds. The researchers argued that this partly stemmed from collectivist cultures putting greater importance in being self-critical, which is less compatible with seeking out confirming as opposed to disconfirming evidence.

Attributions

Psychologists who study social cognition believe that behavior is the product of the situation (e.g., role, culture, other people around) and the person (e.g., temperament, personality, health, motivation). Attributions are beliefs that a person develops to explain human behaviors, characteristics and situations. This means that we try to explain or make conclusions about the causes of our own behavior and others’ behavior. Internal attributions are dispositional (e.g., traits, abilities, feelings), and external attributions are situational (e.g., things in the environment). Our attributions are frequently biased. One way that our attributions may be biased is that we are often too quick to attribute the behavior of other people to something personal about them rather than to something about their situation. This is a classic example of the general human tendency of underestimating how important the social situation really is in determining behavior. Fundamental attribution error (FAE) is the tendency to overestimate the degree to which the characteristics of an individual are the cause of an event, and to underestimate the involvement of situational factors. FAE is considered to be universal but that cultural differences may explain how and when FAE occurs.

Attributions and Culture

On average, people from individualistic cultures tend to focus their internal attributions more on the individual person, whereas, people from collectivistic cultures tend to focus more on the situation (Ji, Peng, & Nisbett, 2000; Lewis, Goto, & Kong, 2008; Maddux & Yuki, 2006). Miller (1984) asked children and adults in both India (a collectivistic culture) and the United States (an individualist culture) to indicate the causes of negative actions by other people. Although the younger children (ages 8 and 11) did not differ, the older children (age 15) and the adults did. Americans made more dispositional attributions, whereas Indians made more situational attributions for the same behavior.

Morris and his colleagues (Hong, Morris, Chiu, & Benet-Martínez, 2000) investigated the role of culture on person perception in a different way, by focusing on people who are bicultural (i.e., who have knowledge about two different cultures). In their research, they used high school students living in Hong Kong. Although traditional Chinese values are emphasized in Hong Kong, because Hong Kong was a British-administrated territory for more than a century, the students there are also enculturated with Western social beliefs and values.

Morris and his colleagues first randomly assigned the students to one of three priming conditions. Participants in the American culture priming condition saw pictures of American icons (such as the U.S. Capitol building and the American flag) and then wrote 10 sentences about American culture. Participants in the Chinese culture priming condition saw eight Chinese icons (such as a Chinese dragon and the Great Wall of China) and then wrote 10 sentences about Chinese culture. Finally, participants in the control condition saw pictures of natural landscapes and wrote 10 sentences about the landscapes.

Then participants in all conditions read a story about an overweight boy who was advised by a physician not to eat food with high sugar content. One day, he and his friends went to a buffet dinner where a delicious-looking cake was offered. Despite its high sugar content, he ate it. After reading the story, the participants were asked to indicate the extent to which the boy’s weight problem was caused by his personality (personal attribution) or by the situation (situational attribution). The students who had been primed with symbols about American culture gave relatively less weight to situational (rather than personal) factors in comparison with students who had been primed with symbols of Chinese culture.

In still another test of cultural differences in person perception, Kim and Markus (1999) analyzed the statements made by athletes and by the news media regarding the winners of medals in the 2000 and 2002 Olympic Games. They found that athletes in China described themselves more in terms of the situation (they talked about the importance of their coaches, their managers, and the spectators in helping them to do well), whereas American athletes (can you guess?) focused on themselves, emphasizing their own strength, determination, and focus.

Most people tend to use the same basic perception processes, but given the cultural differences in group interconnectedness (individualistic versus collectivist), as well as differences in attending (analytic versus holistic), it should come as no surprise that people who live in collectivistic cultures tend to show the fundamental attribution error less often than those from individualistic cultures, particularly when the situational causes of behavior are made salient (Choi, Nisbett, & Norenzayan, 1999). Bias attributions can lead to negative stereotyping and discrimination but being more aware of these cross-cultural differences in attribution may reduce cultural misunderstandings and misinterpreting behavior.