10.1 Group Interactions

L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero

Group Membership

Psychologists study groups because nearly all human activities (e.g., working, learning, worshiping, relaxing, playing, and even sleeping) occur in groups and these groups have a profound impact on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Some researchers believe that groups may be humans’ most useful innovation that facilitated social norms and language development (Boyd & Richerson, 2005; Henrich, 2016; Aiello & Dunbar, 1993). Groups provide us with the means to reach goals that we otherwise wouldn’t if we remained alone. The advantages of group life may be so great that humans are biologically prepared to seek membership and avoid isolation.

Need to Belong

Humans have a powerful need to belong. Baumeister and Leary (1995) describe this need as “a pervasive drive to form and maintain at least a minimum quantity of lasting, positive, and impactful interpersonal relationships (p. 497)” and most of us satisfy this need by joining groups. It doesn’t matter if a person is from Israel, Mexico, or the Philippines, we all have a strong need to make friends, start families, and spend time together. Across individuals, societies, and generations, we consistently seek inclusion over exclusion, membership over isolation, and acceptance over rejection. People who are accepted members of a group tend to feel happier and more satisfied.

When people are deliberate excluded from groups the experience is highly stressful leading to depression, confused thinking, and even aggression (Williams, 2007). When researchers used an fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scanner to track neural responses to exclusion, they found that people who were left out of a group activity displayed heightened cortical activity in two specific areas of the brain, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula. These areas were associated with the experience of physical pain sensations (Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003). It hurts literally, to be left out of a group.

Identity and Membership

Groups not only satisfy the need to belong, they also provide members with a sense of identity, the universal construct that is shaped by our view of ourselves and how we are recognized by others (Chapter 8). Demographic qualities such as sex or age can influence us if we categorize ourselves based on these qualities. Social identity theory asserts that we categorize ourselves and form a social identity based on the degree to which we identify as a member of a particular social group (e.g., man, woman, Anglo, elderly, or college student) (Tajfel & Turner, 1979/1986). We don’t just classify ourselves, we also categorize other people into social categories. Social identity theory explains our tendency to favor an in-group (people we perceive to be like us) over an out–group (people we perceive to be different from us).

When we strongly identify with an in-group, our own well-being becomes bound to the welfare of that group which increases our willingness to make personal sacrifices for its benefit. We see this with sports fans who heavily identify with a favorite team. These fans become elated when the team wins and sad when the team loses. Heavily committed fans often make personal sacrifices to support their team, such as braving terrible weather, paying high prices for tickets, and standing and chanting during games.

People also take credit for the successes of other in-group members, remember more positive than negative information about in-groups, are more critical of the performance of out-group than of in-group members, and believe that their own groups are less prejudiced than are out-groups (Shelton & Richeson, 2005). Attitudes and beliefs about out-groups are often associated with infrahumanization which is the tendency to see out-groups as less human, or as having less humanity than in-groups (Vaes, Paladino, Castelli, Leyens, & Giovanazzi, 2004). We have seen this in history as a justification for genocide or ethnic cleansing (Castano & Giner-Sorolla, 2006). Though a strong group identity can bind individuals together, it can also drive divisions between different groups, reducing overall trust and cooperation on a larger scale. People are generally less likely to cooperate with members of an out-group (Allport, 1954; Van Vugt, Biel, Snyder, & Tyler, 2000).

Triandis and colleagues (1988) found that in/out-group relationships were highly correlated with individualistic and collectivistic values of cultures. Members of individualistic cultures belong to multiple in-groups and move easily from in-group to in-group. People from individualistic cultures were not attached to any one single in-group because they belong to many different groups. Additionally, members were more likely to treat out-group persons more equally, with less distinction between in-groups and out-group. Individuals from collectivistic cultures tended to belong to fewer in-groups than individualistic cultures but had much greater commitment to the groups they belong to.

Consider, if a group leader (e.g., politician, chief, religious figure) has to decide between providing financial support for one program or another. She may be more likely to give resources to the group that more closely represents her own in-group. This psychological process, of being more comfortable with people like yourself, can have important and lasting consequences for the out-group members. In-group favoritism (preferences for the in-group) is found for many different types of social groups, in many different settings, on many different dimensions, and in many different cultures (Bennett et al., 2004; Pinter & Greenwald, 2011). In-group favoritism also occurs on trait ratings, such that in-group members are rated as having more positive characteristics than are out-group members (Hewstone, 1990).

Van de Vliert (2011) examined in-group favoritism using three major components that shape culture: ecology, resources and people (Chapter 2). Using data from almost 180 countries, in-group favoritism was highest in cultures with the lowest income and harshest most demanding climates (e.g., extreme heat or cold) and lowest in cultures with high national income and demanding climates. By examining ecology, national wealth and group preferences collectively, rather than individually, a picture begins to emerge that suggests in-group favoritism likely co-evolved with culture, as groups adapted to survive ecological challenges with limited resources.

Cooperation refers to the ability of humans to work together toward common goals and is required for survival. Groups with better member cooperation were more likely to survive (Bowles et al., 2012). As we learned earlier (see Chapter 2) cooperation occurs in non-human primates (e.g., chimpanzees, bonobos) but it is almost exclusively limited to kin and is almost never extended to strangers (Melis & Semmann, 2010). Some psychologists believe that complex cooperation among humans is related to psychological processes like empathy, trust, group identity, memory, shared intentionality and culture (Matsumoto & Juang, 2013; Moskowitz & Piff, 2018).

Our ability to understand someone’s emotional experience, empathy, occurs when we take on perspective of the person and try to understand his or her point of view. When empathizing with a person in distress, the natural desire to help is often expressed as a desire to cooperate. Trust is the belief that another person’s actions will be beneficial to one’s own interests (Kramer, 1999) which enables us to work together as a single unit. When it comes to cooperation, trust is necessary and critical (Pruitt & Kimmel, 1977; Parks, Henager, & Scamahorn, 1996; Chaudhuri, Sopher, & Strand, 2002); however, our willingness to trust others depends on their actions and reputation. One common example of the difficulties in trusting others that you might be familiar with is a group project for a class. Many students dislike group projects because they worry about social loafing, the way that one person expends less effort but still benefits from the efforts of the group.

Over time, individuals develop a reputation for helping or for loafing. Willingness to cooperate with others depends on their prior actions and reputation and our memory of the events. Nowak and Sigmund (1998) demonstrated with a mathematical model that a person with a reputation for helping gets help later on, regardless of whether they provided help to you directly in the past. In a study that used an economic game, found that as the game progressed donations (help) were more frequently given to individuals who had been generous in earlier rounds of the game (Wedekind & Milinski, 2000). Individuals who were perceived as cooperative gained a reputational advantage, earning them more partners willing to cooperate and a larger overall monetary reward.

There are cultural differences in the belief about the goodness of people, which can be seen as a measure of trust. High trust refers to positive expectations about the behaviors of others (returning a lost wallet) and low trust refers to negative expectations about the behaviors of others (keeping a lost wallet). High trust societies are more likely to cooperate without sanctions (punishment); however, there is a lot of variation in cooperation across cultures (Gatcher et al., 2010) and willingness to sanction group members is moderated by factors like social norms, country gross domestic product (GDP) and individual reputation (whether someone has helped in the past) (Balliet & Van Lange, 2013).

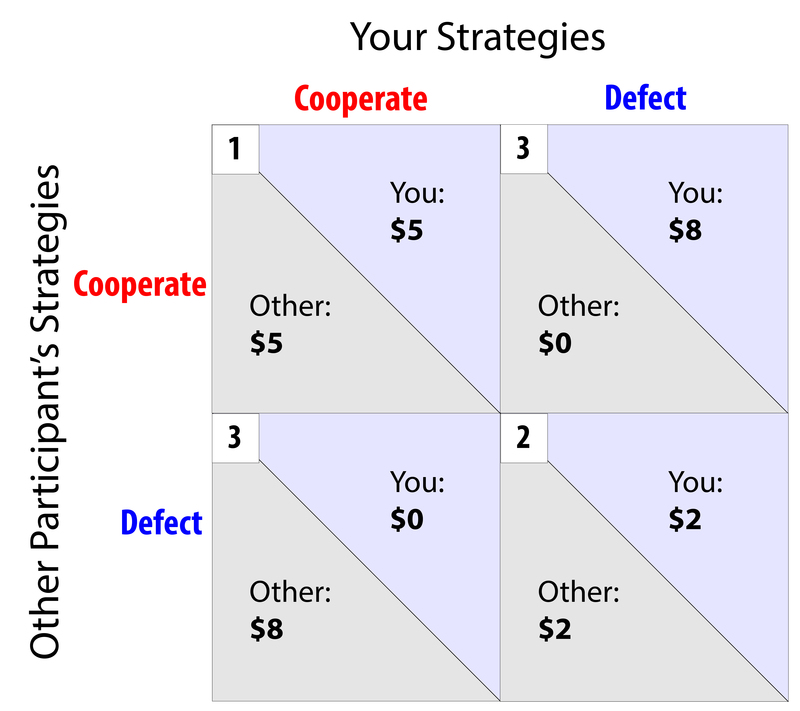

Economists and psychologists often use the Prisoner’s Dilemma to examine cooperation and competition experimental studies. In the prisoner’s dilemma, the participants are shown a payoff matrix in which numbers are used to express the potential outcomes for the each of the players in the game, given the decisions made by each player. The payoffs are chosen beforehand by the experimenter in order to create a situation that is similar to a real-world outcome and are normally arranged so that each individual is better off acting in his or her immediate self-interest. If all individuals act according to their self-interest, then everyone will be worse off. Yamagishi (1986, 1988) categorized Japanese and American participants into low trust and high trust categories and then asked them to take part in an experiment where they could give other participants money (a variation of the prisoner’s dilemma). High trusters provided more cooperation without the presence of sanctions and low trusters provided more cooperation with sanctions. Culture variation in levels of trust (high/low) is present within and across cultures. It appears that across cultures punishment promotes cooperation of social loafers in societies with high trust more than low trust societies (Balliet & Van Lange, 2013). High trust cultures are more willing to punish social loafers. Low trust cultures may not share the social norm of ‘no free rides’ so punishment isn’t going to work in those situations.

Group identification can strongly influence cooperation and people are generally reluctant to cooperate with members of an out-group, or those outside the boundaries of one’s own social group (Allport, 1954). Matsumoto and Hwang (2011) used the Prisoner’s Dilemma to examine whether cultural differences were related to intercultural (between cultures) competition and cooperation. Researchers used the prisoner’s dilemma to test their hypothesis. Students were paired as same-sex and same ethnicity or same sex but different ethnicity. The pairs with different ethnicities had fewer cooperative behaviors and more competitive behaviors.

Using a variation of the Prisoner’s Dilemma among small-scale subsistence societies revealed that the interdependence of a group (i.e., relying on one another for survival) predicted the likelihood of cooperation. For example, among the people of the Lamelara in Indonesia, who survive by hunting whales in groups of a dozen or more individuals, donations in the ultimatum game were extremely high, approximately 58% of the total sum. In contrast, the Machiguenga people of Peru, who are generally economically independent at the family level, donated much less on average, about 26% of the total sum. The interdependence of people for survival, therefore, seems to be a key component of why people decide to cooperate with others (Henrich et al., 2001).

Cooperation is an important part of our everyday lives and even though cooperation can sometimes be difficult to achieve, certain practices, such as emphasizing shared goals and engaging in open communication, can promote teamwork and even break down rivalries. Though choosing not to cooperate can sometimes achieve a larger reward for an individual in the short term, cooperation is often necessary to ensure that the group as a whole is successful.

Although we may be influenced by the people around us more than we recognize, whether we conform to the norm is up to us but sometimes decisions about how to act are not so easy. Sometimes we are directed by a more powerful person to do things we may not want to do. Psychologists who study obedience are interested in how people react when given an order or command from someone perceived to be in a position of authority. In many situations, obedience is a good thing like obeying parents, teachers, and police officers but there is a dark side to obedience. When “following orders” or “just doing my job,” people can violate ethical principles, break laws or harm other people. It was this unsettling side of obedience that led to some of the most famous and most controversial research in the history of psychology.

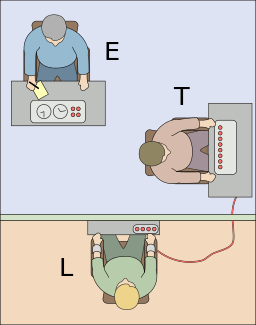

Milgram (1963, 1965, 1974) wanted to know why so many otherwise decent German citizens went along with the brutality of the Nazi leaders during the Holocaust so he conducted a series of laboratory investigations. In his now famous deception study, Milgram found that 65% of research participants were willing to administer, what they believed were, 330-volt electric shocks to a fellow research participant despite hearing cries and protests. No one was hurt or injured during this study, the research participant receiving the electric shocks was a confederate – part of the study – but the actual research participants did not know this. They were willing to administer electric shocks because the experimenter told them to continue. These were not cruel people but they followed the experimenter’s instructions to administer what they believed to be excruciating if not dangerous electric shocks to an innocent person.

Obedience and Culture

The initial research was conducted using male participants but Milgram found that women participants followed the experimenter’s instructions at exactly the same rate that the men had. Some people have argued that today we are more aware of the dangers of blind obedience than we were when the research was conducted in the 1960s; however, findings from partial and modified replications of Milgram’s procedures recently conducted suggest that people respond to the situation today much like they did a half a century ago (Burger, 2009). Cross cultural studies of obedience found rates of obedience similar to those of Milgram. The United States had an obedience rate of 61% and the mean across other cultures was about 66%. Some countries had much lower rates of obedience (India reported 42% and Spain reported about 50%) while some countries had much higher rates of obedience (Germany and Austria reported about 80%) (Blass, 2011). Culture and social norms shape perspectives of authority, obedience and interact with individual decision making.

Decades of research on social influence, including conformity and obedience make it clear that we live in a social world and that, for better or worse, much of what we do reflects the people we encounter and the groups we belong to. Disturbing implications from the research are that, under the right circumstances, each of us may be capable of acting in some very uncharacteristic and perhaps some very unsettling ways.

You have probably noticed that we often adopt the preferences, actions and attitudes of the people around us like fashion, music, foods, and entertainment. Our views on political issues, religious questions, and lifestyles also reflect, to some degree, the attitudes of the people we interact with. Decisions about risk-taking behaviors such as smoking and drinking are also influenced by whether the people we spend time with engage in these activities. Psychologists refer to this tendency to act and think like the people around us as conformity. Consider a classic study conducted many years ago by Solomon Asch (1956). Male college students gave wrong answers to a simple visual judgment task rather than go against the group (Asch, 1956). Variations of Asch’s procedures have been conducted numerous times across many cultures (Bond, 2005; Bond & Smith, 1996) and conformity appears to be a universal construct. Bond and Smith (1996) analyzed the results of 133 studies that used Asch’s line-judging task in 17 different countries that were categorized as collectivist or individualist in orientation. Results were significant, conformity was greater in more collectivist countries than in individualistic countries. Compared with individualistic cultures, people who live in collectivist cultures place a higher value on the goals of the group than on individual preferences. They also are more motivated to maintain harmony in their interpersonal relations.

Conformity and Culture

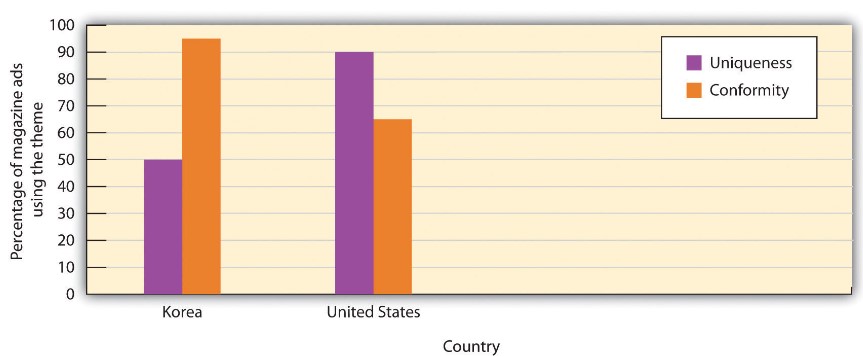

Kim and Markus (1999) examined conformity using advertisements from popular magazines in the United States and in Korea to see if they emphasized conformity and uniqueness differently. As you can see Figure 1, the researchers found that while magazines ad from the United States tended to focus on uniqueness (e.g., “Choose your own view!”; “Individualize”) Korean ads tended to focus more on themes of conformity (e.g., “Seven out of 10 people use this product”; “Our company is working toward building a harmonious society”).

Although the effects of individual differences on conformity tend to be smaller than those of the social context, they do matter. And gender and cultural differences can also be important. Conformity, like most other psychological processes represents an interaction between culture and the individual.