12-5: Workplace Violence

Workplace violence represents a severe threat to worker well-being that has gained increased attention as organizations recognize both its prevalence and serious consequences. The statistics are sobering: from 1992 to 2019, nearly 18,000 persons were killed at work, on duty, or in work-related violence (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). Additionally, more than 2 million American workers reported experiencing physical attacks during the preceding 12 months, while 6 million reported receiving threats. These aren’t just numbers — they represent real people whose safety was compromised at work.

Group Factors in Workplace Violence

Group dynamics play crucial roles in both preventing and contributing to workplace violence, often in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. Team support and psychological safety can serve as protective factors — when people feel supported and safe to express concerns, problems can be addressed before they escalate. But interpersonal conflict and bullying within teams can escalate toward violence, creating powder-keg situations where small incidents can explode into major problems.

Group norms around conflict resolution significantly influence violence risk. Teams that normalize aggressive communication, regularly blame individuals for systemic problems, or lack effective conflict resolution processes create environments where violence becomes more likely. When the team culture is “every person for themselves” or “the loudest voice wins,” it sets the stage for escalation.

Think about it: in teams where people feel heard, respected, and supported, conflicts tend to get resolved through communication. In teams where people feel ignored, disrespected, or threatened, conflicts tend to escalate through increasingly aggressive means.

Understanding Workplace Violence

Interest in workplace violence increased dramatically following high-profile incidents such as the Patrick Sherrill case in Edmund, Oklahoma in 1986, where a postal worker killed 14 coworkers and himself. Such incidents highlighted the need for better understanding of workplace violence causes, prevention, and intervention strategies. While these extreme cases grab headlines, they represent just the tip of the iceberg of workplace aggression and violence.

Research has identified several reliable findings about workplace aggression and violence that can help us understand and prevent it. Higher frustration levels at work correlate with increased incidents of aggression and violence (Martinko & Zellars, 1998). When people feel constantly frustrated, blocked from achieving their goals, or treated unfairly, the risk of aggressive behavior increases significantly.

Individuals who exhibit aggressive and violent behavior have often been rewarded for such behavior in the past, suggesting learned behavioral patterns. If someone has learned that intimidation, threats, or aggressive behavior gets them what they want, they’re likely to continue using these strategies.

Employees with external locus of control orientations — people who believe that external forces rather than their own actions control their outcomes — are more likely to respond aggressively to negative workplace events. When people feel powerless and blame external forces for their problems, they may lash out at available targets.

Understanding Workplace Violence Risk Factors

Multiple factors contribute to workplace violence risk, and understanding these helps organizations and teams develop prevention strategies.

Risk Factors for Assault at Work include:

- Contact with the public during service delivery

- Exchange of money in transactions

- Delivery of passengers, goods, and services in mobile settings

- Working alone or in small groups without backup support

- Working with unstable or distressed individuals

Jobs at greatest risk include retail, healthcare, education, transportation, and social services — occupations that often combine multiple risk factors. Importantly, most workplace violence comes from outsiders rather than current employees, though internal violence receives more media attention.

Individual Risk Factors for Workplace Violence include:

- Mishandled terminations or disciplinary actions

- Bringing weapons onto work sites

- Drug or alcohol use on the job

- Holding grudges over real or imagined grievances

- Personal emotional disturbance

- Hypersensitivity to criticism

- Recent acquisition or fascination with weapons

- Obsession with supervisors, coworkers, or employee grievances

- Preoccupation with violent themes

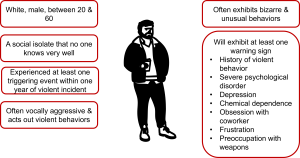

Profile of the Dangerous Employee research has identified patterns that may indicate increased risk, though it’s important to note that these factors are predictive at group levels and should never be used to discriminate against individuals. The profile serves as a guide for understanding risk factors, not for making assumptions about specific people.

Theoretical Frameworks for Understanding Workplace Violence

Several theoretical models help explain workplace violence development and inform prevention strategies:

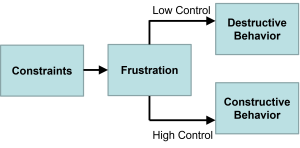

Frustration-Aggression Hypothesis: This theory proposes that frustration leads to aggression, though research has refined this to recognize that aggression is only one possible response to frustration and not everyone responds to frustration aggressively. The modern understanding suggests that frustration leads to stress reactions, and individuals expend energy to relieve this stress, sometimes through destructive or counterproductive behavior.

The key factor determining whether someone engages in destructive behavior is the extent to which they believe the obstacle to goal attainment — and thus the frustration — can be eliminated through constructive behavior. When people see no constructive path forward, they may turn to destructive responses.

Justice Hypothesis of Workplace Violence: This framework suggests that some violent acts can be understood as reactions to perceived injustice. Workers evaluate workplace events according to three types of justice:

- Procedural justice: Issues of due process and whether all individuals receive equal treatment

- Distributive justice: Whether actual outcomes (like layoffs or promotions) are deserved

- Interpersonal justice: The manner in which decisions are communicated — whether compassionately and respectfully or callously and demeaningly

When workers perceive significant violations of these justice principles, risk of aggressive responses may increase.

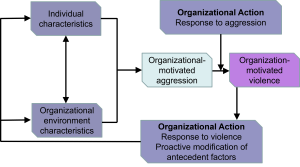

Organization-Motivated Aggression Model: This framework suggests that rigid, punitive, and aggressive organizational cultures may encourage employee aggression. Organizations that model aggressive behavior, fail to address conflicts constructively, or create climates of fear and intimidation may inadvertently promote aggressive responses from employees.

Team-based prevention strategies can significantly reduce violence risk through collective action:

- Clear communication protocols for reporting concerns mean everyone knows how to speak up when they see warning signs. When teams have established, trusted ways to raise concerns about threatening behavior, problems can be addressed before they escalate.

- Team training in conflict de-escalation helps everyone learn skills for calming down tense situations before they get out of hand. When team members know how to recognize escalating conflicts and have tools for defusing them, the workplace becomes safer for everyone.

- Peer support systems for identifying and helping struggling colleagues create networks of care within teams. When teammates look out for each other and know how to connect struggling colleagues with resources, it can prevent problems from developing.

- Group norms that prioritize safety and mutual respect create environments where violence is less likely to occur. When the team culture emphasizes treating everyone with dignity and resolving conflicts constructively, it sets expectations that make violence less acceptable.

Contemporary Prevention Approaches

Modern organizations are implementing increasingly sophisticated violence prevention strategies:

- Surveillance systems and security measures to monitor and respond to threats

- Training programs for employees and managers on recognizing warning signs

- Coaching and counseling services for employees experiencing stress or conflicts

- Effective HR policies that address grievances fairly and promptly

- Active shooter training that many companies now provide given increased concerns about workplace violence

Prevention strategies are also expanding to address subtle, covert, and verbal aggression rather than focusing only on physical violence, recognizing that workplace aggression exists on a continuum that’s best addressed early.

Bullying in the Workplace

Workplace bullying involves harassing, offending, socially excluding, or assigning humiliating tasks to persons in subordinate positions repeatedly over extended periods (Einarsen et al., 2011). Research indicates that bullying rates may reach 25% of the workforce in one-year periods, rising to nearly 50% over five-year periods in some countries. That means up to half of all workers experience bullying over a five-year period — it’s far more common than most people realize.

Group dynamics play central roles in workplace bullying, often determining whether bullying behaviors are stopped or allowed to continue and escalate. Bullying often emerges from power imbalances within teams and can be enabled by group norms that tolerate or encourage aggressive behavior. When teams have cultures where “toughness” is valued over kindness, or where aggressive behavior is seen as leadership, bullying becomes more likely.

Bystander behavior within teams significantly influences bullying outcomes — teams where members intervene to stop bullying create safer environments for all members. Ever witnessed someone being picked on at work and wondered whether you should step in? Your response can make a huge difference. When teams have norms that encourage intervention (“we don’t let people get picked on here”), bullying is less likely to persist.

Bullying Escalation Process

From an organizational perspective, bullying can be understood as the escalation of conflict that typically follows predictable stages:

- Critical incident: A work-related dispute occurs between two individuals

- Bullying and stigmatizing: The person in the inferior position becomes stigmatized and subjected to increasingly aggressive acts by the bully, with intent to damage the victim

- Organizational intervention: The organization steps in and makes the dispute “official”

- Expulsion: The victim (not the bully), now stigmatized and possibly acting in ineffective and traumatized ways, often faces separation from the organization

This pattern shows how organizational responses can sometimes make the problem worse for the victim while protecting the aggressor. The prevalence of bullying appears equally common across professional, white-collar, and blue-collar positions, suggesting that organizational culture and group power dynamics rather than job type determine whether bullying occurs.

Interventions and Future Directions

So what can actually be done about all these workplace well-being challenges? The good news is that addressing worker well-being doesn’t require magic — it requires comprehensive intervention strategies that operate at multiple organizational levels. Effective approaches combine individual-focused interventions with organizational-level changes that address systemic sources of stress and support employee health. Importantly, these interventions must also address group-level factors that significantly influence individual well-being.

Stress Management Interventions

Research demonstrates that stress management interventions can effectively reduce job stress when they’re properly designed and implemented. Cognitive-behavioral interventions show the greatest impact on stress reduction compared to relaxation techniques or purely organizational interventions (Richardson & Rothstein, 2008). These approaches help you develop skills for recognizing, understanding, and managing stress responses — they give you tools for dealing with stress more effectively.

Team-based stress management interventions show particular promise and often work better than individual approaches:

- Group stress management training that helps teams collectively identify and address stressors works better than individual training because it addresses the social context of stress. When the whole team learns stress management skills together, they can support each other and create healthier group norms.

- Team building activities that enhance cohesion and mutual support create stronger support networks for when stress hits. When team members genuinely care about each other and work well together, they can help buffer each other’s stress.

- Communication skills training for teams to improve conflict resolution prevents many stressors from developing in the first place. When teams know how to address problems before they become major conflicts, everyone experiences less stress.

- Shared decision-making processes that increase team members’ sense of control help everyone feel more empowered to manage their work environment. When people have a voice in decisions that affect them, they feel less helpless and stressed.

Individual-level interventions include stress management training, relaxation techniques, time management skills, and coping strategy development. However, research suggests that individual approaches alone prove insufficient for addressing workplace stress, as they fail to address organizational and group sources of stress that create ongoing problems. It’s like trying to stay dry in a rainstorm with just an umbrella when you really need both an umbrella and shelter.

Organizational-Level Interventions

Organizational interventions focus on changing workplace conditions that create stress rather than simply helping you cope with existing stressors. This is like fixing the leaky roof instead of just giving everyone buckets to catch the water. Examples include job redesign initiatives, workload management, improved communication systems, and enhanced supervisor training.

Group-focused organizational interventions include:

- Team structure optimization to ensure appropriate size, composition, and role clarity helps prevent many team-based stressors from developing. When teams are the right size, have complementary skills, and everyone knows their role, many problems are prevented.

- Conflict resolution systems that address interpersonal and intergroup tensions provide clear pathways for resolving problems before they escalate. When teams have established processes for handling conflicts, they don’t fester and grow into bigger problems.

- Team leadership development to enhance team functioning and member support creates leaders who can foster healthy team environments. Good team leaders can prevent many problems and help resolve others quickly.

- Communication system improvements that facilitate effective information sharing prevent misunderstandings and coordination problems. When teams have good communication systems, many stressors simply don’t develop.

The Total Worker Health approach, developed by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), provides a comprehensive framework that integrates health protection and health promotion components (Tamers et al., 2019). Health protection components operate at organizational levels (such as reducing chemical exposures and improving safety procedures), while health promotion components focus on individual wellness (such as smoking cessation programs and fitness initiatives). This approach increasingly recognizes team health as a crucial component of worker well-being.

Organizations implementing Total Worker Health approaches demonstrate improvements in worker health and safety outcomes. This integrated approach recognizes that effective intervention requires addressing individual, group, and organizational factors that influence worker well-being. You can’t just focus on one level and expect comprehensive results.

Conclusion

Worker well-being represents a fundamental concern for both employees and organizations in contemporary work environments. The field of occupational health psychology provides evidence-based approaches for understanding, measuring, and improving workplace conditions that affect employee health and safety. However, as this enhanced module demonstrates, individual well-being cannot be separated from group dynamics and team effectiveness. You don’t work in isolation — you work as part of teams, and those teams have huge impacts on your health and happiness.

Why should you care about this as a future professional? Because effective approaches to worker well-being require comprehensive understanding of stress processes, work-family dynamics, employment security, workplace safety, and the group processes that either support or undermine these individual experiences. Organizations that invest in both individual and team-level well-being demonstrate improved employee engagement, retention, and performance while reducing healthcare costs and legal liabilities. It’s not just the right thing to do — it’s smart business.

Key insights from integrating group dynamics into worker well-being include:

Stress is socially constructed: How you experience and cope with stress is significantly influenced by your team environment, group norms, and the social support available from colleagues. The same stressor can feel totally manageable or completely overwhelming depending on your team context. It’s like the difference between facing a challenge with a supportive crew versus facing it alone.

Team dysfunction multiplies individual stressors: Poor group communication, interpersonal conflict, and dysfunctional team processes don’t just add to your stress — they multiply its impact by undermining your coping resources. It’s like trying to recover from illness while being exposed to more germs — the environment makes everything worse.

Group interventions can be more powerful than individual interventions: Addressing team-level issues often produces more sustainable improvements in individual well-being than focusing solely on individual coping skills. Fixing the environment is often more effective than just helping people cope with a bad environment. Why teach people to swim in toxic water when you can clean up the water?

Psychological safety is foundational: Teams that create environments where members feel safe to be vulnerable, make mistakes, and express concerns provide crucial protection against stress and burnout. When you don’t have to waste energy protecting yourself from your teammates, you have much more energy for everything else.

Team effectiveness and individual well-being are mutually reinforcing: High-performing teams tend to have healthier, more satisfied members, while individual well-being contributes to team effectiveness. It’s a positive cycle that benefits everyone — good teams create healthy individuals, and healthy individuals create good teams.

The evidence clearly supports integrating both individual and team-level considerations into organizational strategy and daily operations. Rather than viewing employee health as separate from business objectives, successful organizations recognize that team health and individual well-being are essential for sustainable competitive advantage and ethical business practice.

Future developments in worker well-being will likely emphasize prevention-focused approaches, technology-enabled interventions, and comprehensive support systems that address the whole person within their team and organizational context. Success requires ongoing collaboration between researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to develop evidence-based solutions that promote healthy, productive, and meaningful work experiences at both individual and group levels.

As work environments continue evolving — with remote work, changing demographics, technological disruption, and shifting employee expectations — worker well-being research and practice must adapt to address emerging challenges while maintaining focus on fundamental human needs for safety, respect, purpose, and balance. These needs are best met within supportive, effective team environments that recognize the interconnected nature of individual and group well-being.

Organizations that prioritize both individual and team well-being position themselves to attract top talent, maintain high performance, and contribute positively to society while achieving business objectives. It’s not an either/or proposition — you can be both profitable and humane.

Whether you become a manager, employee, consultant, or entrepreneur, understanding the intersection of individual well-being and group dynamics isn’t just academic knowledge — it’s essential for creating workplaces where people can thrive, perform their best, and maintain their health and happiness as members of effective, supportive teams. The choices you make in your career about how to treat people, design work environments, and structure team interactions will have real impacts on human well-being.

Remember: You don’t just work as an individual — you work as part of teams, groups, and organizational systems. Your well-being depends not only on your individual characteristics and coping skills but also on the quality of relationships, communication, and support within your team. Similarly, your behavior as a team member significantly influences the well-being of your colleagues. Understanding this interconnection is crucial for creating truly healthy workplaces.

The workplace of the future will be defined not just by technology, flexibility, or benefits packages, but by the quality of human connections and the effectiveness of teams in supporting both performance and well-being. That future starts with the choices you make today about how you want to work with others and what kind of team member — and eventually, what kind of leader — you want to be.

Your well-being at work isn’t just about you — it’s about the ecosystem you’re part of and the ecosystem you help create for others. Make it a good one.

Media Attributions

- Stop Workplace Violence © Wisconsin Nurses Association

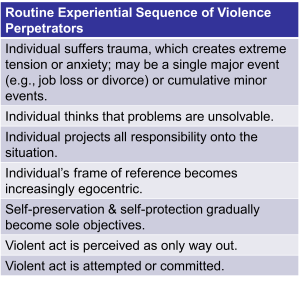

- Routine Experiential Sequence of Violence Perpetrators

- Frustration-Aggression Hypothesis adapted by Jay Brown

- Profile of Potential Workplace Violence Indicators adapted by Jay Brown

- Model of Organization-Motivated Aggression adapted by Jay Brown