1-3: History of I/O Psychology

Before World War I: Setting the Stage

The early 1900s were like the Silicon Valley boom of their time—massive, disruptive change happening at breakneck speed. The industrial revolution had created huge factories and office buildings where hundreds or thousands of people worked together, something humanity had never really dealt with before on this scale.

Here’s something interesting to consider: even those early offices had more in common with modern workplaces than you might think. People were:

- Working both individually and in teams

- Storing and accessing information (filing cabinets instead of cloud storage)

- Using cutting-edge technology (typewriters and telephones instead of laptops and smartphones)

- Building relationships and navigating office politics

- Attending formal meetings and presentations

- Dealing with deadlines and performance expectations

The basic human elements of office work haven’t changed as much as the technology—we’ve just upgraded the tools while dealing with the same fundamental challenges of getting people to work together effectively.

Frederick Taylor and the Efficiency Revolution

Enter Frederick Taylor and his “Principles of Scientific Management” in 1911 (Taylor, 1911). Taylor had what seemed like a simple, logical idea: apply scientific methods to figure out the most efficient way to do any job.

Taylor’s approach involved breaking complex tasks down into simple, repetitive activities. He timed workers with stopwatches, analyzed their movements frame by frame, and redesigned work processes to eliminate any “wasted” motion. On paper, this sounds pretty reasonable—who doesn’t want to work more efficiently?

But Taylor’s system was built on some problematic assumptions about human nature. He basically viewed workers as naturally lazy and believed they needed constant supervision and financial incentives to stay productive. This led to workplace environments where:

- Workers performed highly repetitive, specialized tasks with little variety

- Socializing was discouraged as “wasteful” and distracting

- Management maintained strict control and constant surveillance

- People were treated more like components in a machine than as human beings with needs, feelings, and ideas

While Taylorism dramatically increased productivity in many settings, it also created some of the workplace problems that I/O psychology continues to address today—like how to maintain employee motivation and job satisfaction in highly structured work environments, and how to balance efficiency with human dignity.

The Academic Pioneers

Walter Dill Scott was one of the first academics to systematically apply psychology to business problems. He was actually a student of Wilhelm Wundt (one of psychology’s founding fathers), but Scott was way more interested in practical applications than laboratory experiments. In 1901, he gave a talk in Chicago about the psychological aspects of advertising, which led to his groundbreaking book “Theory and Practice of Advertising” in 1903 (Scott, 1903). By 1911, he had published “Influencing Men in Business” and “Increasing Human Efficiency in Business.”

Scott wasn’t just writing about workplace psychology—he was literally inventing it from scratch, establishing concepts and methods that we still use today. He was figuring out how psychological principles could be applied to real business challenges like motivation and productivity.

Walter Van Dyke Bingham (Bingham, 1952) founded the Division of Applied Psychology at Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1915, which was huge because it was the first major academic program dedicated to applying psychology to business problems. The Division provided:

- Entrance testing for students to help with academic placement

- Vocational guidance to help people find suitable careers

- Psychology and education courses that bridged theory and practice

- Research partnerships with local businesses to solve real problems

Bingham recognized that businesses everywhere faced similar fundamental challenges: How do you identify and select good employees? How do you train them effectively? How do you measure and improve performance fairly? His program began developing standardized, research-based approaches to these universal workplace questions. Interestingly, Scott became the Division’s first professor, showing how these pioneers collaborated and built on each other’s work.

Hugo Munsterberg at Harvard published “Psychology and Industrial Efficiency” in 1913 (Munsterberg, 1913), earning him recognition as the “father of industrial psychology.” What’s remarkable about Munsterberg is how broad his perspective was for the time. He argued that managers should be concerned with “all the questions of the mind… like fatigue, monotony, interest, learning, work satisfaction, and rewards.”

This holistic view—that psychology should address the full range of human experience at work, not just productivity—continues to characterize the field today. Munsterberg understood that you can’t separate the person from the worker. He was also a founding member of the American Psychological Association and is considered the father of forensic and clinical psychology too—talk about a Renaissance man!

World War I: The Field Proves Itself

World War I provided a massive opportunity for I/O psychology to prove its value on a scale nobody had ever attempted. Robert Yerkes, who was president of the American Psychological Association at the time, led the development of the Army Alpha and Army Beta tests—intelligence tests designed to classify military personnel into appropriate jobs.

This was absolutely groundbreaking for several reasons:

- It was the first large-scale use of psychological testing in history (they tested about 1.7 million soldiers)

- It demonstrated that psychology could handle huge, logistically complex challenges

- It showed that systematic assessment could dramatically improve job placement and performance

- It established many of the principles still used in employee selection today

- It proved that psychological methods could have real, measurable impact on organizational effectiveness

The war effort also brought together many of the field’s early leaders, including Bingham and Scott in key military roles. When they returned to civilian life after the war, they brought with them proven methods, impressive track records, and a lot of credibility with business leaders.

Bruce V. Moore received the first Ph.D. specifically in I/O psychology from Carnegie Tech in 1921. For his dissertation, he created an early version of what would eventually become the Strong Interest Inventory—a tool still used today to help match people’s interests with suitable careers.

The field was growing rapidly: from just 10 practicing I/O psychologists in 1917 to 50 by 1929. Psychology was officially in the workplace to stay.

The 1920s and 1930s: The “O” Side Emerges

The Psychological Corporation, founded by James Cattell in 1921, had a fascinating dual mission: advance psychology as a science while promoting its practical usefulness to industry. The Corporation also served as a quality control mechanism, helping companies find qualified psychologists and protecting the field’s reputation from unqualified practitioners trying to cash in on psychology’s growing popularity.

What’s interesting is that this organization, which started as a professional credentialing body, eventually evolved into one of the largest publishers of psychological tests in the world. Today, it serves as one of the biggest test publishers rather than just a referral service. This evolution shows how professional institutions adapt and grow to serve changing needs in their fields.

During this period, the “O” side of I/O psychology really started to emerge as research and practice began focusing on group processes, worker motivation, and other organizational phenomena rather than just individual job performance.

The Hawthorne Studies: Everything Changes

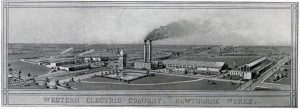

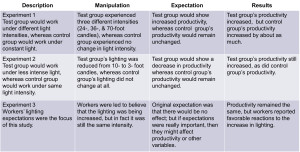

Between 1924 and 1932, researchers conducted a series of studies at Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works that fundamentally changed how we think about workplace behavior. These Hawthorne Studies (Roethlisberger & Dickson, 1939) started with what seemed like a simple question: Does better lighting make workers more productive?

What they discovered was much more interesting and complicated than anyone expected.

What they discovered was much more interesting and complicated than anyone expected.

The researchers found that worker productivity increased regardless of whether they improved the lighting, dimmed it, or left it exactly the same. This led to the recognition of what we now call the “Hawthorne Effect”—the idea that people change their behavior when they know they’re being observed and studied.

But the real breakthrough was recognizing that social and psychological factors could be more important than physical working conditions. The studies revealed that:

- Workers’ relationships with their supervisors had enormous impact on performance

- Group norms and peer pressure could override individual incentives

- Feeling valued, listened to, and respected could boost productivity more than pay raises

- Social factors could completely override economic incentives

- The informal organization (relationships and social dynamics) was just as important as the formal organization chart

This was revolutionary because it shifted attention from the individual worker in isolation to the social context of work. It helped launch what we now call organizational psychology—the study of how groups, leadership, and organizational culture affect individual and collective behavior.

World War II: Another Quantum Leap

World War II again provided opportunities for I/O psychology to tackle massive, high-stakes challenges. Bingham and Scott continued their contributions, while new research centers emerged, including Kurt Lewin’s Center for Group Dynamics at MIT and the Army Research Institute (ARI).

Some major WWII contributions included:

- The Army General Classification Test, used to classify an estimated 12 million soldiers into appropriate roles

- Assessment centers developed for the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (the precursor to the CIA) to identify candidates for intelligence and special operations work

- Research on performance under extreme stress and in life-or-death situations

- Studies of leadership effectiveness in combat and crisis conditions

- Development of personnel counseling techniques

The OSS assessment centers were particularly innovative and influential. Instead of just giving people paper-and-pencil tests, they put candidates through realistic simulations and observed how they handled complex, ambiguous, high-pressure situations. They looked at problem-solving under stress, leadership in crisis, ability to work with diverse team members, and performance when the stakes were life and death.

This approach was so successful that it became the foundation for modern assessment center techniques still used today by organizations ranging from Fortune 500 companies to fire departments to NASA.

The Modern Era: 1950s to Today

The Field Comes of Age

By the 1950s, I/O psychology was firmly established as both a legitimate scientific discipline and a valuable professional service. University programs were expanding rapidly across the country, and the field was developing increasingly sophisticated theories and research methods.

Major Developments Since 1980

Civil Rights and Fairness: The civil rights movement and subsequent legislation made fairness in employment a central legal and ethical concern. I/O psychologists had to ensure that selection tests and other HR practices didn’t discriminate against protected groups. This challenge led to major advances in understanding test validation, bias detection, and fairness in assessment.

The Cognitive Revolution: Psychology as a whole began paying much more attention to mental processes—how people think, make decisions, process information, and solve problems. In I/O psychology, this led to better theories of motivation, more sophisticated models of leadership, and deeper understanding of organizational behavior.

Technology Transformation: The internet and digital technology revolutionized both how I/O psychologists conduct research and how they deliver services to organizations. Online testing, virtual training programs, remote work arrangements, and big data analytics all created new opportunities and challenges.

Work-Life Integration: As family structures changed and dual-career couples became the norm, the boundaries between work and personal life became increasingly blurred. I/O psychologists began studying how to help people manage these competing demands without burning out or sacrificing important relationships.

Team-Based Work: Organizations increasingly recognized that complex problems require collaborative solutions from diverse groups of people. This drove extensive research on team composition, team processes, virtual teamwork, and team effectiveness.

Organizational Justice: Researchers began systematically studying fairness perceptions—how people’s sense of being treated fairly affects their attitudes, behavior, performance, and commitment to the organization.

Stress and Well-being: Beginning in the late 1980s and continuing into the 1990s, workplace stress received increasing attention in I/O research, theory, and practice as organizations recognized the enormous costs of stress-related health problems, absenteeism, and turnover.

360-Degree Feedback: Instead of performance evaluation coming only from your boss, this approach gathers input from supervisors, peers, subordinates, and sometimes customers, providing a more complete and balanced picture of someone’s strengths and development needs.

Workplace Violence Prevention: Unfortunately, highly publicized incidents of workplace aggression and violence in the mid to late 1990s made threat assessment and violence prevention a necessary area of research and intervention.

Key Milestones Timeline

Here are some major developments that shaped the field into what it is today (Ferguson, 1962-1965; Katzell & Austin, 1992; Koppes, 2007; Vinchur & Koppes, 2007):

- 1892: American Psychological Association founded

- 1935: Hoppock conducts the first major systematic study of job satisfaction

- 1946: APA Division 14 (I/O Psychology) officially established with Bruce Moore as the first president

- 1947: General Aptitude Test Battery developed for vocational guidance

- 1954: Critical Incident Technique introduced for job analysis

- 1956: AT&T Management Progress Study begins (landmark longitudinal study of managerial careers)

- 1963: Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scales (also called Behavioral Expectation Scales) developed for performance evaluation

- 1964: Civil Rights Act Title VII passed; Expectancy Theory of motivation developed

- 1969: Job Descriptive Index and Position Analysis Questionnaire created

- 1975: SIOP’s first Principles for validation and use of personnel selection procedures published

- 1976: First Handbook of I/O Psychology published; Job Diagnostic Survey developed

- 1977: Meta-analysis statistical technique introduced to I/O psychology

- 1986: SIOP Midyear Conference established

- 1987: Attraction-Selection-Attrition Model proposed to explain organizational culture

- 1998: O*NET launched (comprehensive online database of occupational information)

- 1999: Revised Standards published

- 2002: O*NET version 4.0 released

- 2018: SIOP’s 5th edition Principles published, reflecting current best practices

Media Attributions

- Antique Books © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Frederick Taylor © Gessford is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Offices Across Time © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hugo Munsterberg © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Soldier Taking a Precursor to the Army Alpha © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hawthorne Works © Western Electric Company is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hawthorne Illumination Studies