10-1: What is Motivation?

It’s Monday morning, and you’re sitting at your desk feeling like you could take on the world. You’re energized, focused, and ready to tackle that project you’ve been putting off. Fast forward to Thursday afternoon of the same week, and you can barely muster the energy to check your email. Sound familiar?

It’s Monday morning, and you’re sitting at your desk feeling like you could take on the world. You’re energized, focused, and ready to tackle that project you’ve been putting off. Fast forward to Thursday afternoon of the same week, and you can barely muster the energy to check your email. Sound familiar?

You might be wondering, “What’s going on here? Why am I so motivated some days and completely checked out on others?” Welcome to one of the most fascinating puzzles in psychology — the mystery of human motivation at work!

Organizational psychology is the systematic study of dispositional and situational variables that influence the behaviors and experiences at work. But here’s what makes this field so mind-blowing: as researchers put it, organizational psychology “is intimately tied to the recognition that organizations are complex social systems, and that almost all questions one may raise about the determinants of individual human behavior within organizations have to be viewed from the perspective of the entire social system.”

Think about your workplace for a moment. It’s not just a bunch of individual people doing their jobs in isolation, right? You’ve got your coworkers who either energize you or drain your soul, your boss who might inspire you or make you want to hide under your desk, the company culture that either makes you proud to work there or has you updating your resume, and countless other factors swirling around you every single day. Your motivation doesn’t exist in a vacuum — it’s part of this incredibly complex web of relationships and influences.

Now, here’s where it gets really interesting. Back in the early days of workplace research, people thought motivation was pretty straightforward — give people good lighting, comfortable chairs, maybe a decent paycheck, and boom! Motivated workforce. Then came the famous Hawthorne studies, which completely flipped this thinking on its head.

These studies revealed something that blew researchers’ minds: the psychological environment at work is as important as, or even more important than, the physical environment in determining how people perform and feel about their jobs. In other words, whether people actually notice and care about you, how you fit in with your team, and whether your psychological needs are being met can matter more than whether you have the latest ergonomic chair or perfect lighting.

Defining Motivation

Let’s cut to the chase and talk about what motivation actually is. Motivation is the force that drives people to behave in certain ways. Think of it as your internal engine — the thing that gets you moving and keeps you going when things get tough.

This internal engine has three main jobs, and they all work together to determine how you show up at work every day:

First, motivation energizes your behavior. It’s what creates the force that results in some level of effort expenditure. You know that feeling when you’re really excited about a project and you find yourself working late because you’re genuinely into it? That’s the energizing power of motivation at work.

Second, motivation directs your behavior by focusing that energy toward specific objectives rather than letting it scatter in random directions. Without direction, you might have tons of energy but end up spinning your wheels on tasks that don’t really matter.

Third, motivation sustains your behavior by maintaining that effort over extended periods of time, even when obstacles pop up or the initial excitement wears off. This is the difference between starting strong and actually finishing what you started.

Here’s where things get tricky, though: motivation cannot be measured directly. You can’t stick a thermometer in someone’s brain and get a motivation reading. You can only figure out how motivated someone is by watching what they do, listening to what they tell you, and looking at how well they perform. This creates real challenges for researchers trying to study motivation, which explains why there are so many different theories floating around trying to crack this code.

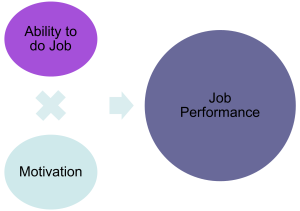

The Biggest Workplace Myth: Motivation Equals Performance

Now, you might be thinking, “Well, if someone’s not performing well, they’re obviously not motivated, right?” Hold up — this is actually one of the biggest misconceptions managers have in the workplace, and it gets people into trouble all the time.

There’s a mistaken belief by many managers that if performance is low, it must be because motivation is not present. But here’s the reality check: performance depends on way more factors than just motivation.

Picture this scenario: You’re incredibly motivated to crush that big presentation, but your computer keeps crashing, you never received proper training on the software you need to use, and your instructions were about as clear as mud. You could be the most motivated person in the building and still deliver a mediocre presentation.

On the flip side, think about that naturally gifted classmate you had who could ace tests without studying while you pulled all-nighters just to get a B. They might have achieved decent performance with minimal motivation, coasting on pure talent.

The takeaway? Don’t assume that poor performance automatically means someone doesn’t care or isn’t trying. There might be skill gaps, resource constraints, unclear expectations, or a dozen other factors at play.

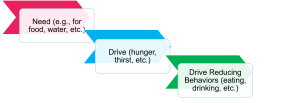

Drive-Reduction Theory and Homeostasis

One of the earliest attempts to crack the motivation code was drive-reduction theory. This theory suggests that your body’s physiological needs create uncomfortable tension states (called drives) that motivate you to satisfy those needs and relieve the discomfort. It’s basically like having an internal alarm system that goes off when something’s out of balance.

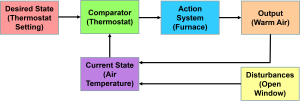

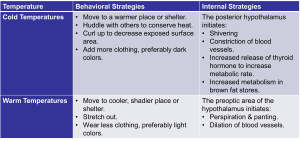

This connects to a concept called homeostasis, which was coined by Cannon (1932). Homeostasis refers to your body’s ability to adjust its processes to maintain equilibrium. Think of it like a really sophisticated thermostat that doesn’t just control temperature — it manages everything from your blood sugar to your sleep cycles.

Your body has set points for things like core temperature and body weight, and when you drift away from these targets, regulatory processes kick in to bring you back to balance. It’s like your body is constantly running a background program to keep everything stable.

The process works as a goal-directed feedback system involving several key components: your desired state (the set point), a comparator (the mechanism that checks your current status), your current state (where you actually are right now), and an action system (the behaviors that help you get back on track).

Here’s how it plays out in real life: when you’re hungry, that uncomfortable gnawing feeling motivates you to find food. When you’re cold, you’re driven to seek warmth. When you’re tired, you start looking for ways to rest. The system works through these feedback loops that constantly monitor where you are versus where you need to be.

This cybernetic model gives us a solid foundation for understanding basic motivation, but it has some pretty obvious limitations. What about behaviors that don’t serve any clear biological function? Why do people voluntarily seek out challenging activities that actually increase stress and arousal rather than reducing it? These questions led researchers to develop more sophisticated theories.

Optimum Arousal Theory

Here’s where motivation theory gets more interesting and realistic. Your biological rhythms naturally cycle through periods of varying arousal levels throughout the day, and you’re actually motivated to maintain arousal within an optimal range rather than just minimizing it all the time.

Optimum arousal theory emerged to explain behaviors that don’t seem to serve obvious biological needs — like curiosity, thrill-seeking, and the drive to learn new things. When you feel under-aroused (think about sitting through a mind-numbingly boring lecture), you actively seek stimulation through challenging activities, social interaction, or novel experiences. When you feel over-aroused (like when you’re completely stressed and overwhelmed), you engage in calming activities to bring your arousal down to more comfortable levels.

Have you ever watched a young child explore everything in sight, driven by pure fascination? That’s exploration motivation in action. They’re not fulfilling any immediate physiological need — they’re satisfying an intrinsic drive for stimulation, challenge, and mastery. This same drive shows up in adults who seek out challenging hobbies, learn new skills for fun, or take on difficult projects just because they’re interesting.

This has huge implications for your work life. It suggests that you might be motivated by opportunities for challenge, learning, and growth rather than just by removing discomfort or satisfying basic needs. Jobs that provide optimal levels of challenge and stimulation can enhance your motivation, while positions that are either too demanding or insufficiently challenging can actually reduce your engagement.

Achievement Motivation

Achievement motivation represents your desire for significant accomplishment, mastery of skills or ideas, and attainment of high standards. This isn’t about wanting to achieve one specific thing — it’s more like a personality trait that represents your general drive to excel across different situations.

Need for achievement (nAch), as studied by McClelland (1961), develops through specific life experiences. You’re more likely to develop strong achievement motivation if you were encouraged to be independent and try new activities, received praise and rewards when you mastered new tasks, grew up in environments that fostered achievement, and experienced contexts where effort was encouraged without harsh punishment for unsuccessful attempts.

Need for achievement (nAch), as studied by McClelland (1961), develops through specific life experiences. You’re more likely to develop strong achievement motivation if you were encouraged to be independent and try new activities, received praise and rewards when you mastered new tasks, grew up in environments that fostered achievement, and experienced contexts where effort was encouraged without harsh punishment for unsuccessful attempts.

People high in need for achievement show some fascinating patterns:

- They perform better in school and work settings

- They actively seek out challenges rather than playing it safe

- They’re more willing to try new things and take on novel activities

- They set higher goals for themselves

- They show greater willingness to delay immediate gratification for bigger long-term rewards

- They prefer moderate risks over extreme ones

The Ring-Toss Experiment: Here’s a classic demonstration that perfectly illustrates achievement motivation in action. Researchers gave people a ring-toss game and let them choose how far to stand from the target.

People with low achievement motivation typically chose one of two extremes: they either stood very close to the target (where success was virtually guaranteed regardless of skill) or very far away (where failure could be blamed on the impossible difficulty rather than lack of ability).

But people with high achievement motivation consistently chose intermediate distances — spots where their actual abilities would determine success or failure. They wanted outcomes that genuinely reflected their personal competence. They wanted to know that their success (or failure) was really theirs.

Learned Helplessness

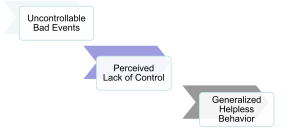

At the opposite end of the spectrum from achievement motivation lies learned helplessness — and this one’s really important to understand because it can creep into workplace situations more easily than you might think.

The concept comes from Seligman’s (1972) groundbreaking experiments with dogs. When dogs were repeatedly subjected to inescapable electric shocks, something disturbing happened: they eventually stopped trying to escape even when escape became possible. They had learned that their actions were ineffective in controlling outcomes, so they just gave up trying altogether.

Learned helplessness is characterized by several warning signs:

- Feelings of powerlessness and lack of control

- Beliefs that develop from repeated failure experiences

- Convictions that situations simply can’t be overcome

- The belief that you can’t affect your future

- The belief that there’s no hope for change

People experiencing learned helplessness typically show:

- Low motivation and persistently negative mood

- Reluctance to seek help from others, even professionals

- Cognitive impairment that affects problem-solving

- Lack of appropriate responses, even when action is clearly warranted

- Generally sad and listless behavior

Personal control emerges as a critical factor in preventing learned helplessness. People thrive when they’re given appropriate choices and real opportunities to influence their work environments. Research in nursing homes found that residents who had little control over their daily activities declined faster than those with greater autonomy. This finding extends directly to workplaces — employee empowerment and meaningful participation in decision-making can prevent or even reverse helpless orientations while boosting motivation and well-being.

Intrinsic Versus Extrinsic Motivation

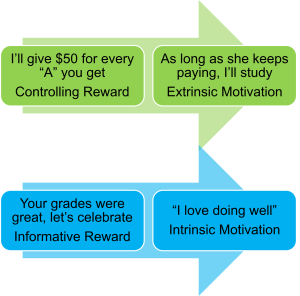

This distinction is absolutely fundamental to understanding workplace behavior and designing effective motivational strategies. Get this wrong, and you can actually make motivation problems worse instead of better.

Extrinsic motivation involves wanting to perform behaviors because of promised rewards or threats of punishment. When your behavior is controlled by external factors, it typically stops as soon as the external pressure is removed. Think about how students often forget everything they “learned” right after a test — they were motivated by grades, not genuine interest in the material.

Intrinsic motivation represents wanting to perform behaviors for their own sake — to experience effectiveness, mastery, and personal satisfaction. Intrinsically motivated behaviors are self-sustaining and often lead to enhanced creativity, deeper learning, and greater satisfaction.

Here’s the key insight that can transform how you think about motivation: effective motivation often involves cultivating intrinsic motivation through tasks that challenge and trigger curiosity while avoiding excessive use of extrinsic rewards that may actually undermine people’s sense of self-determination.

Recent research by McAnally and Hagger (2024) has further demonstrated that autonomous forms of motivation and basic psychological need satisfaction are related to better employee performance, satisfaction, and engagement, while controlled forms of motivation and need frustration are associated with increased employee burnout and turnover.

Three Evidence-Based Strategies for Motivating People

Based on decades of research, here are three proven approaches to enhancing motivation:

Cultivate Intrinsic Motivation: Set tasks that challenge people and trigger their natural curiosity. Avoid reducing people’s sense of self-determination by relying too heavily on external rewards and punishments.

Pay Attention to Individual Motives: Different people are genuinely motivated by different things. In the workplace, these might include accomplishment, recognition, social affiliation, or the opportunity to exercise power and influence. Take time to understand what actually drives the people you work with.

Set Specific, Challenging Goals: Provide clear objectives along with regular progress reports. This gives people something concrete to aim for and helps them track their advancement toward meaningful targets.

Media Attributions

- Maintaining War Workers’ Morale © Unnown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Job Performance © Jay Brown

- Drive Reduction Theory © Jay Brown

- Maintaining Homeostasis adapted by Jay Brown

- Maintain Body Temperature Homeostasis

- Graduates © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Shuttle Box © Rose Spielman is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Learned Helplessness © Jay Brown

- Extrinsic & Intrinsic Motivation © Jay Brown

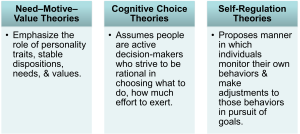

- Theoretical Perspectives on Motivation