10-2: Need-Value-Motive Theories of Motivation

Need-motive-value theories start with a simple but powerful idea: your behavior is driven by attempts to satisfy various needs, whether they’re biological, psychological, or social. These theories have been incredibly influential in developing workplace interventions, even though the research support for their specific claims is sometimes shakier than we’d like.

Need-motive-value theories start with a simple but powerful idea: your behavior is driven by attempts to satisfy various needs, whether they’re biological, psychological, or social. These theories have been incredibly influential in developing workplace interventions, even though the research support for their specific claims is sometimes shakier than we’d like.

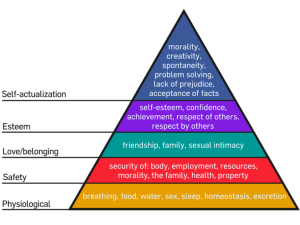

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s hierarchy is probably the most famous motivational theory you’ll ever encounter. You’ve likely seen those pyramid diagrams in other classes, and there’s a reason this theory has stuck around for so long — it captures something intuitive about human nature.

The theory proposes that humans are driven by needs that are biological and instinctive, organized into five levels:

Physiological needs (food, water, shelter, sleep) form the foundation. These are your survival basics — the stuff you literally can’t live without.

Safety needs (security, protection, stability) come next. This includes both physical safety and psychological security, like job security and financial stability.

Love and belongingness needs (social relationships, acceptance, affiliation) represent your drive to connect with others and feel like you belong to something bigger than yourself.

Esteem needs (recognition, achievement, respect from others) reflect your desire to feel valued and respected both by yourself and by the people around you.

Self-actualization needs (personal growth, fulfillment of potential, creativity) sit at the top of the pyramid. This is about becoming the best version of yourself and realizing your unique potential.

The theory suggests that lower-order needs (physiological, safety, and love) must be reasonably satisfied before higher-order needs (esteem and self-actualization) become motivationally significant. It’s like climbing a ladder — you need to secure each rung before you can focus on the next level.

Here’s the key organizational insight: Different employees are likely at different places in the hierarchy, so no single motivational approach can work for everyone. You need to assess where individual employees are and tailor your strategies accordingly.

A new employee struggling to pay rent might be primarily motivated by compensation and job security, while a well-established employee might be more interested in opportunities for creative expression and professional growth.

Despite its intuitive appeal and widespread use, Maslow’s hierarchy has received limited research support. Critics point out that it assumes universal need progression without considering individual and cultural differences, and it’s notoriously difficult to define and measure the proposed need categories. But here’s the thing — even if the specific details don’t hold up perfectly, it still provides a useful framework for thinking about the variety of human needs.

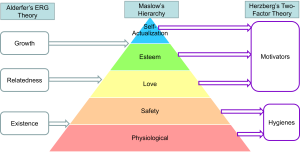

Alderfer’s ERG Theory

ERG theory, developed by Alderfer (1972), represents a smart modification of Maslow’s hierarchy that addresses some of its major limitations. The theory streamlines the five-need hierarchy down to three categories while allowing much more flexibility in how needs actually operate in real life.

Existence needs correspond to Maslow’s physiological and safety needs — basically, your material requirements for survival and security. This covers everything from food and shelter to job security and reasonable working conditions.

Relatedness needs parallel love and belongingness needs, focusing on your social relationships and interpersonal connections. This includes family relationships, friendships, and the social aspects of work.

Growth needs combine esteem and self-actualization, emphasizing your interactions with the environment and your drive to master challenges, develop new skills, and realize your potential.

The theory introduces a couple of key concepts. Satisfaction represents the internal state that arises from obtaining what you’re seeking, while desire reflects concepts like want or the intensity of need strength.

Unlike Maslow’s theory, ERG theory proposes that all three need categories can operate simultaneously rather than requiring step-by-step satisfaction. This makes way more sense when you think about real life — you can be working on growth and development while still caring about your relationships and basic security.

The theory also introduces frustration-regression — the idea that when you’re frustrated at higher levels, you might refocus energy on satisfying lower-level needs. Ever notice how when you’re stressed about career advancement (growth), you might seek more social connection with coworkers (relatedness)? That’s frustration-regression in action.

ERG theory provides greater flexibility in explaining individual differences while maintaining the insight that human needs vary in focus and priority. The simultaneous operation of multiple need levels better reflects the complexity of how motivation actually works in real workplace settings.

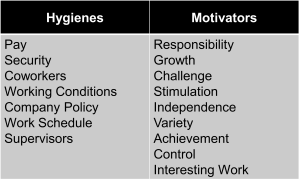

Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory

Here’s where things get really counterintuitive, and this theory might change how you think about job satisfaction forever. Herzberg’s two-factor theory (1966) proposes that what makes you satisfied at work is fundamentally different from what makes you dissatisfied. This completely challenges the common assumption that satisfaction and dissatisfaction are just opposite ends of the same scale.

The theory identifies two distinct types of factors:

Hygienes relate to job context and can lead to dissatisfaction when they’re absent or inadequate. Examples include supervisory problems, low pay, poor working conditions, and inadequate company policies. Here’s the crucial insight: the presence of adequate hygienes leads to neutrality rather than satisfaction. They prevent dissatisfaction, but they don’t create motivation.

Motivators are factors that actually lead to satisfaction and motivation: recognition, interesting work, responsibility, advancement opportunities, and achievement. The presence of motivators creates satisfaction and motivation, while their absence results in neutrality rather than dissatisfaction.

Think about it this way: fixing a terrible work environment might stop people from complaining, but it won’t necessarily make them excited about their jobs. You could have perfect working conditions, fair pay, and great management, but if the work itself is boring and meaningless, people still won’t be genuinely motivated.

To create real motivation, you need to focus on the content of jobs and provide opportunities for recognition, responsibility, and growth.

The practical implication: To ensure that your workforce will be satisfied and motivated to perform, it’s not enough to provide reasonable working conditions and compensation (hygienes). The actual content of the job (motivators), such as meaningful work relationships and recognition for contributions, must be addressed as well.

This explains why some people can be miserable in jobs with great benefits and pay, while others thrive in challenging roles even when the external perks aren’t spectacular.

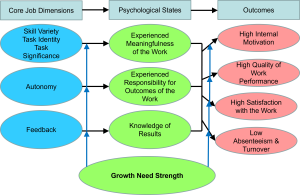

Job Characteristics Theory

Job Characteristics Theory (Hackman & Oldham, 1976) represents one of the most sophisticated and well-researched frameworks for understanding workplace motivation. It emphasizes the fit between individuals and jobs while providing systematic approaches to changing jobs to better match human needs and preferences.

The theory proposes that any job can be described using five core dimensions:

Skill variety refers to how much the job requires different skills and talents. Jobs high in skill variety let you use multiple abilities and prevent boredom from repetitive tasks.

Task identity involves whether the job allows you to complete whole, identifiable pieces of work rather than just small fragments. It’s the difference between building an entire product versus just installing one bolt on an assembly line.

Task significance represents how much the job impacts other people’s lives or work. Jobs high in task significance give you a sense that what you do actually matters to others.

Autonomy reflects how much freedom, independence, and discretion you have in scheduling your work and determining your procedures. High autonomy means you have real control over how you get things done.

Feedback represents how clearly your work activities provide information about your performance effectiveness. Good feedback lets you know whether you’re succeeding and where you can improve.

These five core dimensions influence three critical psychological states that are necessary for motivation:

Experienced meaningfulness results from skill variety, task identity, and task significance. Essentially, this is about feeling like your work matters and has genuine value.

Experienced responsibility derives from autonomy. This is about feeling real ownership of your outcomes rather than just following orders mindlessly.

Knowledge of results stems from feedback about performance effectiveness. This psychological state involves actually knowing how you’re doing rather than operating in the dark.

When all three psychological states are present, you experience high motivation, high-quality performance, high satisfaction, and low absenteeism and turnover. It sounds almost too good to be true, but the research consistently supports these relationships.

However, there’s an important individual difference factor: growth need strength — how much you personally value fulfilling higher-order needs. If you have high growth need strength, you’ll respond more strongly to jobs that are high in the core dimensions. If you have low growth need strength, you may be less responsive to job enrichment efforts.

Job Enrichment and Job Crafting

Job enrichment involves strengthening the motivating potential of jobs by enhancing the key variables identified in Job Characteristics Theory. Rather than just adding more tasks (which might just create more boredom), enrichment focuses on making jobs more intrinsically motivating.

Enrichment efforts might include increasing skill variety through cross-training opportunities, enhancing task identity by allowing people to complete whole projects from start to finish, improving task significance by helping people understand how their work connects to the organization’s mission, providing greater autonomy through flexible scheduling and decision-making authority, and improving feedback through better performance monitoring and communication systems.

Common applications include flexible work arrangements, telecommuting options, technology upgrades that make work more efficient and interesting, changes in information flow that keep people better informed, and assignment of new or different responsibilities that utilize people’s strengths and interests.

Job crafting represents a more recent approach that gives you flexibility to customize or modify your own job rather than waiting for changes to be imposed by management. This is about taking initiative to shape your work experience in ways that better fit your needs and preferences.

Idiosyncratic deals (I-deals) allow you to negotiate with your supervisor about specific job conditions and arrangements that meet both your needs and organizational requirements. These might involve adjusting your schedule, taking on different responsibilities, working from different locations, or focusing on projects that particularly interest you.

You can attempt to remove tasks that you find demotivating while adding tasks that you genuinely enjoy, creating a more personalized and engaging work experience. Research shows that more successful I-deals typically follow from good relationships with supervisors and are related to more favorable job characteristics, greater initiative, and higher engagement levels.

Acquired Needs Theory

McClelland’s acquired needs theory proposes that individual needs result from experiences you acquire throughout life, and leaders can motivate people by understanding these needs and finding ways to foster their development.

According to McClelland, there are three primary needs that can be measured using the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), where people view ambiguous pictures and create stories about them. These responses are evaluated and analyzed to identify ratings for each of the three needs.

Achievement-oriented employees want satisfaction from accomplishing projects successfully and exercising their talents to attain success. They tend to be self-motivated when jobs provide sufficient challenge and opportunities for mastery.

Power-oriented employees seek satisfaction from influencing and controlling others. They enjoy leadership roles and persuasion activities, responding well to positions that provide authority and influence over important decisions.

Affiliation-oriented employees gain satisfaction from interacting with others. They tend to be highly social and find the social aspects of the workplace rewarding, preferring collaborative environments and team-based activities.

Extended Acquired Needs Theory

Bess (2012) extended the original three needs to seven categories, providing a more comprehensive framework for understanding individual differences:

Achievement: These employees want the satisfaction of accomplishing projects successfully. They want to exercise their talents to attain success and are self-motivated when the job is challenging enough.

Power: These employees want satisfaction from influencing and controlling others. They like to lead and persuade, and are motivated by positions of power and leadership.

Affiliation: These employees gain satisfaction by interacting with others. They tend to be highly social, enjoy people, and find the social aspects of the workplace rewarding.

Autonomy: These employees seek freedom and independence. They like to work and take responsibility for their own tasks and projects without constant supervision.

Esteem: These employees seek recognition and praise. They dislike vague generalities, so praise should be for specific accomplishments and doesn’t necessarily need to be public.

Safety & Security: These employees seek job security, a steady income, insurance benefits, and a hazard-free work environment.

Equity: These employees want to be treated fairly. They tend to compare work hours, job duties, salary, and privileges with those around them and will become discouraged if they perceive inequities.

Understanding individual need profiles enables managers to tailor motivational approaches effectively. Those high in achievement need respond well to challenging assignments and performance feedback, while those high in affiliation need prefer team-based activities and social recognition.

Why Research Support for Need Theories Is Limited

You might be wondering why these intuitive theories don’t have stronger research backing. Several methodological challenges limit research support:

The inability to adequately measure needs (since they’re hard to define operationally) creates major methodological problems and leads to flawed studies. It’s really difficult to create reliable measures for abstract concepts like “self-actualization” or “belongingness.”

There’s also the challenge of defining and measuring the proposed need categories in ways that work across different cultures and individuals. What looks like “esteem” to one person might look like “security” to another.

Many theories make assumptions about universal need progression without adequately considering individual and cultural differences. Not everyone progresses through needs in the same order or at the same pace.

However, here’s what’s important: while limited research supports these theories in their exact original forms, they’ve been instrumental in developing other well-supported motivational theories. They’ve provided the foundation for more sophisticated approaches to understanding workplace motivation.

Media Attributions

- Motivation © U3190069 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs © Factoryjoe is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Hygienes & Motivators

- Job Characteristics Model adapted by Jay Brown

- Comparing Need-Motive-Value Theories © Jay Brown