10-3: Cognitive Choice Theories of Motivation

Cognitive choice theories take a fundamentally different approach to understanding motivation. Instead of focusing on inner needs or environmental forces, these theories propose that you function as a rational decision-maker who weighs alternatives and chooses behaviors based on expected outcomes. They emphasize conscious decision-making processes and your cognitive evaluation of different alternatives.

Equity Theory

Equity theory, developed by J. Stacy Adams (1965), focuses on something that’s absolutely crucial in workplace motivation but often gets overlooked: your perceptions about fairness. The theory proposes that your feelings about fairness significantly affect your motivation, attitudes, and behaviors at work.

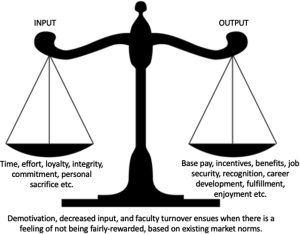

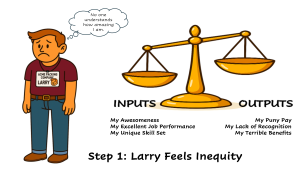

Here’s how it works: According to equity theory, you constantly compare ratios of what you bring to situations (inputs) with what you receive (outcomes) against similar ratios for other relevant people. Your input-outcome ratio is meaningless by itself — the meaning emerges through social comparison with others in similar situations or with your own past experiences.

Inputs include factors like your education, effort, ability, skills, knowledge, experience, and the diverse perspectives you bring to the table. Basically, everything you contribute to your work situation.

Outcomes encompass compensation, benefits, recognition, enhanced self-concept, learning experiences, and advancement opportunities. This includes both tangible rewards and intangible benefits you receive from your work.

Here’s something interesting: people with high self-esteem tend to overestimate their inputs, viewing their mere presence as valuable. They operate with an attitude that’s almost like “my very presence here is a gift to this organization.”

Research consistently supports the idea that motivation decreases when you perceive your input-output ratio as lower than those of relevant comparison others. This has huge implications for compensation systems, promotion decisions, and other organizational practices that distribute rewards and recognition.

How Equity Theory Actually Works

The theory operates on several key principles that explain why fairness matters so much:

People naturally strive to maintain a state of equity in their relationships and work situations. When inequity is perceived, psychological tension results. When faced with this tension, you’re motivated to reduce it somehow. The greater the magnitude of perceived inequity, the stronger your motivation to take action to reduce the tension.

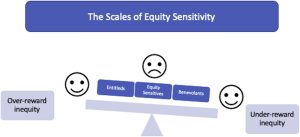

Equity sensitivity represents an individual difference in how much people are affected by over-reward or under-reward situations. Some people are more sensitive to these imbalances than others.

How People Reduce Perceptions of Inequity

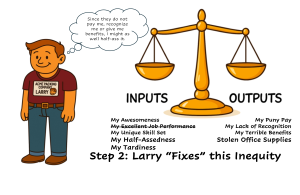

When you perceive inequity, you have several strategies available to reduce the resulting tension:

Changing inputs might involve altering your effort levels. If you feel underpaid and can’t get a raise, you might reduce your work effort to bring your inputs in line with your outcomes.

Changing outcomes involves actively seeking raises, additional recognition, or other improvements in what you receive from work.

Altering perceptions allows you to convince yourself that the ratios are actually equitable. If you feel overpaid, you definitely won’t ask for a pay cut, but you might alter your perceptions to believe that your contributions are much more valuable than you initially thought.

Changing comparison others involves selecting different people to compare yourself against — people who make your current input-outcome ratios appear more favorable.

What Research Tells Us About Equity

Research on equity theory reveals some fascinating and consistent patterns:

When your inputs exceed your outcomes (underpayment):

- You work less hard

- You become more selfish in your behavior

- You report lower job satisfaction

When your outcomes exceed your inputs (overpayment):

- You’re less likely to be persuaded by underpaid peers who complain

- You typically don’t feel guilty about the situation

- You actually work harder to justify the higher rewards

- You become more team-oriented in your approach

One of the most interesting studies looked at professional basketball players and found that overpaid players responded by being more team-oriented (passing the ball more, focusing on rebounds), while underpaid players became more selfish (taking more shots for themselves). This illustrates how equity perceptions can directly influence cooperation and team effectiveness.

The bottom line? Fairness isn’t just a nice-to-have — it’s fundamental to motivation and performance.

Expectancy Theory

Expectancy theory, developed by Vroom (1964), takes a different approach by proposing that you behave in certain ways because you’re motivated to select specific behaviors based on what you expect the results to be. This cognitive approach emphasizes rational decision-making and how you form expectations about the future.

Vroom defines motivation as a process of making choices among alternative forms of voluntary activities — a process that you control. He argues that “intensity of work effort depends on the perception that an individual’s effort will result in a desired outcome.”

The theory identifies three critical components that interact to determine your motivational force:

Expectancy (E) represents your belief about the relationship between effort and performance, ranging from 0 to +1. High expectancy means you believe that increased effort will lead to improved performance, while low expectancy suggests that effort and performance are weakly related. If you think working harder won’t actually improve your results, your expectancy is low.

Instrumentality (I) reflects your belief that performance will result in particular consequences, also ranging from 0 to +1. High instrumentality means you believe that good performance will lead to desired outcomes, while low instrumentality suggests that performance and outcomes are disconnected. This is about whether you trust that good work will actually be rewarded.

Valence (V) represents the value you personally place on rewards or outcomes, ranging from -1 to +1. Positive valence indicates outcomes you desire, negative valence reflects outcomes you want to avoid, and zero valence represents outcomes you’re neutral about.

The theory proposes that these components interact according to the formula: Motivational Force = E × I × V. This multiplicative relationship means that if any component is zero or negative, motivation will be minimal. All three components must be positive for strong motivation to occur.

Applying Expectancy Theory in Practice

Organizations can influence motivation by identifying weak factors in the motivational chain and addressing them. If you’re in a management role and want to apply Vroom’s theory, you should focus on three key areas:

Offer outcomes that have high valence for your employees. This means understanding what people actually want, not just what you think they should want.

Clarify instrumentalities by making it crystal clear that high performance is consistently associated with positive outcomes. People need to see that good work actually gets rewarded.

Clarify expectancies by ensuring that people understand how their efforts translate into improved performance. This might involve providing better training, clearer instructions, or more adequate resources.

Research Findings on Expectancy Theory

Research on expectancy theory shows some interesting patterns:

The theory predicts intentions better than it predicts actual behaviors. People might intend to work hard based on their expectations, but other factors can interfere with follow-through.

Some researchers suggest that adding the components rather than multiplying them might be more appropriate, since multiplication means that a zero in any component results in zero motivation, even when the other components are high.

The theory works best when people behave rationally (which doesn’t always happen) and have an internal locus of control (believing they can influence outcomes through their actions).

Despite these limitations, expectancy theory provides valuable insights into how people make decisions about their work effort and helps explain why identical motivational approaches can have very different effects on different people.

Current research by Grant (2021) has emphasized the importance of understanding prosocial motivation — the desire to benefit others — as a powerful complement to traditional expectancy theory approaches, particularly in team-based work environments where individual efforts contribute to collective outcomes.

Media Attributions

- Perceiving Equity © Elsevier Health is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- The Scales of Equity Sensitivity © Elsevier Health is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Equity Theory Step 1 © Jay Brown and Copilot

- Equity Theory Step 2 © Jay Brown and Copilot

- Equity Theory Step 3 © Jay Brown and Copilot