10-4: Regulation Theories of Motivation

Regulation theories shift the focus to something equally important but often overlooked: how you actually manage your own behavior and make adjustments while pursuing goals. These theories deal with willpower and self-regulation rather than just intentions or choices. They address the crucial question of how you maintain motivation and persist in goal pursuit after you’ve already decided what you want to achieve.

Willpower as a Cognitive Resource

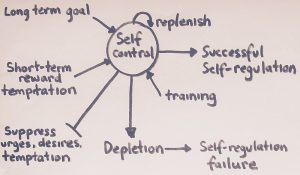

Baumeister’s groundbreaking research conceptualizes willpower as the cognitive resource required for self-regulation, and this research has some pretty mind-blowing implications for how you manage your work life.

Here’s the key insight: willpower functions like a muscle. The more you exercise it, the stronger it becomes over time, but it also gets fatigued if you use it extensively in short periods. Just like you can’t do bicep curls all day without your muscles giving out, you can’t make tough decisions and resist temptations all day without your willpower getting depleted.

Willpower requires actual energy from your body, and your self-regulation capacity gets reduced in several predictable situations: when your blood glucose is low (yes, being hungry actually makes it harder to resist temptations and make good decisions), when you’re tired or fatigued, and when you’re experiencing stress.

Willpower might best be defined as the ability to resist impulses or the ability to do things that don’t come naturally to you. This highlights just how effortful self-regulation really is and explains why maintaining motivation over extended periods can be so challenging.

The Time Travel Problem of Self-Control

Here’s a fascinating way to think about self-control: if we imagine ourselves existing across time, we can refer to our present-self and our future-self as almost different people with different interests.

In self-control situations, your present-self must sacrifice so that your future-self can benefit. Think about saving money, eating healthy, or working hard on a degree — your present-self gives up immediate pleasures so your future-self can enjoy the benefits.

This creates similar challenges to social cooperation, where your present-self must sacrifice, but it’s other people who benefit (like returning your shopping cart to the corral, holding the door for someone behind you, or leaving a tip for good service).

Successful self-control and social cooperation both seem to require trust. Do you trust your future-self to appreciate the sacrifices you’re making today? Do you trust other people to reciprocate when you make sacrifices for them?

Understanding willpower as a limited cognitive resource has important practical implications for workplace motivation. Tasks requiring sustained self-control might be more effectively scheduled when you have adequate energy reserves, and organizations might need to provide support systems that reduce unnecessary demands on your self-regulation capacity.

For example, if you know you have a big presentation to prepare that will require sustained focus and effort, you might want to schedule it for when your willpower reserves are full rather than at the end of a long, decision-heavy day.

Goal-Setting Theory

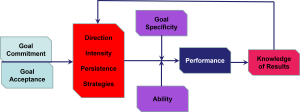

Goal-setting theory proposes that goals function as powerful motivational forces, with people who set specific, difficult goals consistently performing better than those who adopt vague “do your best” goals or no goals at all. This theory represents one of the most consistently supported motivational theories in all of organizational psychology.

Goals affect and motivate behavior through four primary mechanisms:

Goals direct attention to particular tasks rather than letting your efforts scatter across competing activities. When you have a clear goal, your brain naturally filters information and opportunities through the lens of that goal.

Goals mobilize on-task effort by providing clear performance targets. Having a specific goal gives you something concrete to work toward and helps you calibrate your effort level.

Goals enable persistence by providing benchmarks for continued effort. When you hit obstacles or setbacks, clear goals help you stay committed rather than giving up.

Goals facilitate strategies at higher cognitive levels that can be used to move toward goal attainment. Specific goals help you think more strategically about the best approaches to achieve what you want.

Goal commitment represents the internalized aspects of goals — how much you personally buy into and feel ownership of the goal. Goal acceptance refers to assigned goals that you acknowledge and agree to work toward. Both commitment and acceptance are necessary for goals to actually influence motivation and performance effectively.

Effective goal setting requires attention to several key characteristics. Goals should be specific rather than vague (“increase sales by 15%” rather than “do better”), difficult but achievable rather than too easy or impossibly hard, and accompanied by regular feedback about progress. Participation in goal setting can enhance commitment, though properly implemented assigned goals can also be effective.

The practical applications are extensive and well-documented. Organizations can enhance motivation and performance by helping people establish appropriate goals, providing the necessary resources for goal attainment, monitoring progress regularly, and adjusting goals as circumstances change.

Recent research by Grenier et al. (2024) has extended goal-setting theory to team contexts, demonstrating how individual goal-setting processes can emerge at the team level through collective identity construction and shared psychological need satisfaction.

Control Theory

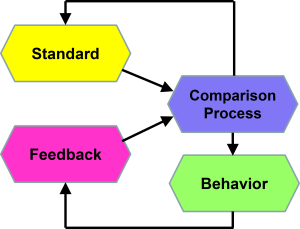

Control theory represents a family of motivational theories centered around negative feedback loops — basically, the idea that motivation results from comparisons between performance feedback and goals or standards, with discrepancies creating tension that motivates corrective action.

Carver and Scheier’s approach emphasizes that people are naturally goal-directed and use goals, intentions, values, and personal aspirations in daily life to move forward. The discrepancy between your standards and your actual behavior becomes particularly important if you’re high in self-focus and more likely to notice and respond to performance gaps.

Think of it like a thermostat system: you set a target temperature (your goal), the system constantly monitors the current temperature (feedback), and when there’s a gap, the heating or cooling system kicks in (corrective behavior) to bring things back to the target.

Control theory suggests several self-regulatory tactics you can use to improve your performance:

Seeking feedback serves as a way of developing skills and achieving task mastery by providing information about your current performance relative to your standards. Rather than avoiding feedback (which many people do), actively seeking it out becomes a powerful tool for improvement.

Proactive behavior involves seeking constructive change rather than just accepting the status quo. This enables you to modify situations to better support goal attainment rather than just reacting to whatever happens.

The feedback loop central to control theory operates continuously throughout your workday. You’re constantly monitoring your performance, comparing it to your standards, and adjusting your behavior when you detect discrepancies. This process requires attention and effort, but it can become more automatic with practice and experience.

Media Attributions

- Strength Model of Self-Control © Reeve is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Goal-Setting Theory adapted by Jay Brown

- Control Theory adapted by Jay Brown