11-1: Attitudes

You’re lying in bed Sunday night, and that familiar feeling starts creeping in. Tomorrow is Monday. How do you feel about that? Are you excited to dive into your work, or are you already hitting the snooze button in your mind? That gut reaction you just had? That’s your job attitude talking – and trust me, it’s way more powerful than you might think.

Think about the best job you’ve ever had. What made it absolutely amazing? Now flip that – what about the worst job you’ve ever experienced? What made you want to run screaming from the building? The difference between these two experiences isn’t just luck or coincidence. It comes down to something psychologists call job attitudes, and they’re one of the most important factors in whether you love or hate your work life.

Here’s what’s fascinating: job attitudes aren’t just about whether you like your job or not. They’re complex psychological constructs that include job satisfaction, organizational commitment, job involvement, and perceived organizational support. Think of them as the ingredients in a recipe – each one influences your behavior in different but connected ways, creating patterns that affect your motivation, performance, and whether you stick around or start updating your résumé.

But here’s the thing that makes this especially relevant today – organizations are dealing with challenges that would have blown the minds of managers from previous generations. We’ve got remote work reshaping everything, multiple generations working side by side with completely different expectations, and technology changing faster than most people can keep up. The old-school “you work, we pay you” deal has evolved into something much more complex, where employees want respect, growth opportunities, and actual work-life balance. Understanding attitudes isn’t just nice to have anymore – it’s essential for survival.

Why should you care about all this? Because when employees feel good about their jobs, everyone wins. Research consistently shows that organizations with more positive employee attitudes crush their competition across multiple measures while spending way less money on turnover, sick days, and dealing with problem behaviors. It’s like the ultimate win-win situation.

What Are Attitudes Really? Definition and Components

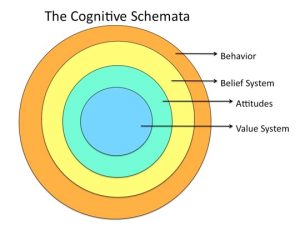

Let’s start with the basics, but don’t worry – this isn’t going to be dry and boring. An attitude is basically your mental shortcut for how you’re predisposed to think, feel, and act toward specific things in your work environment. Think of attitudes as your brain’s way of saying, “Oh, I know how to deal with this situation.”

You might be thinking, “Okay, but aren’t attitudes just simple likes and dislikes?” Not quite! Here’s where it gets interesting – attitudes actually have three parts working together like a well-oiled machine.

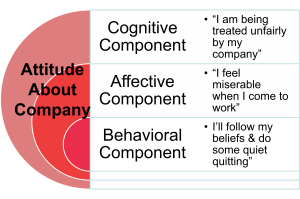

The cognitive component is the “thinking” part of your attitude. It’s all your beliefs, knowledge, and thoughts about whatever you’re dealing with. In your work life, this might include what you believe about job security, how fair you think your company is, or your assessment of whether you’ll actually get promoted someday. For example, you might think, “My company has a solid track record of promoting people who work hard.”

The affective component is the “feeling” part – your emotions and gut reactions. This is often the stickiest part of attitudes and the hardest to change. It might include feeling proud to work for your organization, getting frustrated with your boss’s management style, or feeling excited about challenging new projects. Using our promotion example, you might feel genuinely excited when you think about moving up in the company.

The behavioral component is the “acting” part – what you’re inclined to actually do. While attitudes don’t perfectly predict every single thing you’ll do, they definitely influence your general patterns of behavior over time. So you might actively seek out leadership opportunities, volunteer for additional training, or recommend your company to friends looking for jobs.

Here’s what’s really interesting: these three components don’t always line up perfectly. You might logically know your job is pretty good (cognitive), but still feel frustrated with it (affective), while continuing to work hard (behavioral). When these parts conflict, it creates psychological tension that motivates you to either change your attitude or change your behavior. We’ll dive deeper into this fascinating phenomenon when we talk about cognitive dissonance theory.

Why Do We Even Have Attitudes? Psychological Functions

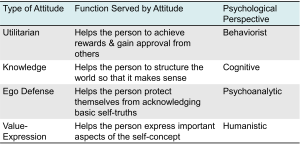

You’re probably wondering, “Why do our brains even bother with attitudes? What’s the point?” Great question! Attitudes actually serve several important functions that help explain why they form, stick around, and sometimes resist change like a stubborn mule.

The knowledge function is like having a mental filing system. Attitudes help you organize and make sense of all the complex information flooding your brain every day. When you have positive attitudes toward your supervisor, for example, you’re more likely to interpret their unclear emails in a favorable way. It’s like wearing rose-colored glasses for information processing – everything gets filtered through your existing attitudes.

The instrumental function is all about helping you get what you want while avoiding what you don’t want. It’s the practical, self-interested side of attitudes. You might develop positive attitudes toward company policies that benefit you (hello, flexible work arrangements!) while forming negative attitudes toward policies that make your life harder (goodbye, mandatory Saturday meetings). Your attitudes become tools for navigating your work environment effectively.

The value-expressive function lets you show the world who you are and what you stand for. You might have strong attitudes toward workplace diversity initiatives because they reflect your fundamental values about equality and social justice. When your organization aligns with your values, you’re likely to develop stronger positive attitudes and deeper commitment. It’s like wearing your values on your sleeve.

The ego-defensive function is your psychological bodyguard, protecting your self-esteem and helping you avoid uncomfortable truths. If you’re struggling with performance issues, you might develop negative attitudes toward the performance review system rather than acknowledging you need to step up your game. It’s not the most mature response, but it’s human nature to protect our egos.

These functions don’t operate in isolation – they’re all working simultaneously and sometimes pulling you in different directions. Understanding this gives organizations opportunities to create positive change by addressing the underlying psychological needs that drive your attitudes.

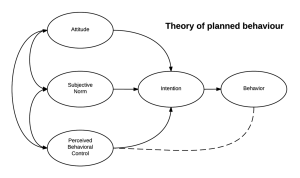

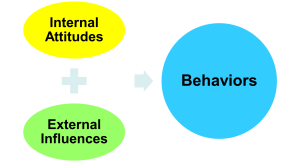

The Science Behind Attitude-Behavior Links: Theory of Planned Behavior

The Theory of Planned Behavior, developed by Ajzen (1985), gives us a framework for understanding when and why your attitudes actually translate into action. This theory assumes you’re generally a rational person who considers the consequences of your actions and chooses behaviors that will give you the best outcomes. Your behavioral intentions are the best predictors of what you’ll actually do.

The theory identifies three key factors that determine whether you’ll actually follow through on your intentions. Attitudes toward the behavior represent how you feel about performing specific actions. Notice this is different from general attitudes – you might love your organization overall but hate the idea of working overtime on weekends.

Subjective norms are all about social pressure – what you think important people expect from you and how motivated you are to meet those expectations. Ever felt pressure to stay late because “that’s just what we do here,” even when there’s no official policy requiring it? That’s subjective norms in action. These workplace norms can be incredibly powerful, sometimes overriding your personal preferences entirely.

Perceived behavioral control is essentially your confidence level – whether you believe you can actually pull off a particular behavior. It’s similar to self-efficacy. You might have great intentions to help your coworkers more, but if you don’t feel confident in your ability to be truly helpful, you’re less likely to follow through.

Here’s the cool part: these three factors work together to predict your behavioral intentions, which then predict your actual behavior. However, their relative importance varies depending on who you are, what behavior we’re talking about, and the specific situation you’re in. Understanding this helps organizations design better interventions by targeting the right factors for behavior change.

Where Do Attitudes Come From? The Formation Process

Understanding how attitudes develop is like getting the blueprint for managing them effectively. Attitudes form through multiple psychological processes that operate over different time periods and in various contexts.

Modeling processes show us that you pick up a lot of attitudes by watching and copying people you respect, especially during your early years. Kids often adopt their parents’ attitudes toward work, authority, and achievement, and these attitudes can stick around well into adulthood. Organizations can use this by making sure leaders and respected employees demonstrate the attitudes and behaviors they want to see. Ever notice how new employees often mirror the attitudes of their mentors? That’s modeling in action.

Classical conditioning works by pairing things with positive or negative experiences to create emotional associations. You’ve seen this in advertising when products are associated with attractive people, great music, or beautiful imagery. In the workplace, this might mean associating company symbols with positive experiences or making sure performance feedback happens in supportive rather than threatening environments.

Operant conditioning uses consequences – rewards and punishments – to shape attitude development. If you get recognition for showing company loyalty, you’ll probably develop stronger positive attitudes toward the organization. On the flip side, if you get negative consequences for speaking up about problems, you might develop less favorable attitudes toward organizational communication. It’s basic human psychology – we move toward rewards and away from punishments.

Direct experience with things often creates stronger and more lasting attitudes than just hearing about them. If you personally experience fair treatment during a major organizational change, you’ll typically develop more positive attitudes toward change management than if you only read about fairness policies in the employee handbook. This is why “walking the talk” is so crucial in organizations.

Exposure effects demonstrate that simply being around something repeatedly tends to make you like it more, even without any special reinforcement. This explains why you often develop more favorable attitudes toward coworkers, policies, and procedures over time through simple familiarity. It’s like how a song can grow on you – the more exposure you have, the more positive your attitude tends to become.

Do Our Attitudes Actually Guide Our Actions? The Complex Reality

Here’s where things get interesting – and honestly, a bit messy. While common sense suggests that your attitudes should predict your behavior (if you love your job, you’ll work hard), research shows this relationship is often weaker and more complicated than we’d expect.

Think about it this way: you might absolutely love pizza, but that doesn’t mean you eat it for every meal. Similarly, your attitudes guide your actions, but only under certain conditions.

Your attitudes are most likely to drive your behavior when external influences are minimal. You might privately believe certain company policies are completely ineffective, but still follow them because of social pressure, formal requirements, or fear of consequences. Understanding when situational pressures override attitude influences is critical for predicting behavior. Think about teenagers who believe drugs are harmful but still use them because of peer pressure.

Attitude specificity makes a huge difference in behavior prediction. Your general attitudes toward your organization might not predict specific behaviors like showing up on time or helping coworkers, while your attitudes toward those specific behaviors show much stronger relationships. If organizations want to influence particular behaviors, they need to focus on relevant specific attitudes rather than assuming general satisfaction will automatically translate into desired actions.

Attitude accessibility affects how well attitudes predict behavior – attitudes that come easily to mind show stronger behavioral relationships. Attitudes you’ve really thought through typically predict behavior better than gut reactions you’ve never examined. This is why it’s important to actually reflect on your attitudes rather than just going with your first instinct.

Measurement considerations complicate things because what people say they feel might differ from what they actually feel. Social pressure might lead you to express attitudes you think are expected rather than your genuine feelings. Some researchers suggest that the 2016 U.S. presidential election reflected differences between publicly expressed and privately held attitudes, with voting behavior revealing attitudes not captured in traditional polling.

The Power of Patterns: Principle of Aggregation

Here’s a key insight that might surprise you: the principle of aggregation suggests that attitude effects become much clearer when you look at patterns of behavior over time rather than isolated incidents. While attitudes might not predict any single behavior very well, they often show strong relationships with behavioral patterns across time and situations.

Think about a baseball player with a .400 batting average – you can’t predict what will happen in any specific at-bat, but you can confidently predict that about 400 of every 1,000 at-bats will result in hits. Similarly, an employee who genuinely dislikes their job might occasionally perform well or help coworkers, but their overall pattern of behavior will likely reflect their negative attitudes through lower performance, more sick days, or reduced helpful behaviors.

Here’s an amusing example that illustrates this perfectly: “I hate squid – you can usually predict my behavior toward squid. But I was on a job interview and the employer ordered calamari as an appetizer…” This shows how specific situations can override general attitudes, but the overall pattern remains predictable.

This principle has important implications for how organizations should think about attitude management. Instead of expecting perfect attitude-behavior correspondence in every situation, focus on how attitudes affect overall behavioral patterns. Performance management systems should recognize that employees with positive attitudes will demonstrate more favorable behavioral patterns over time, even if they occasionally have off days.

The Flip Side: How Our Actions Shape Our Attitudes

While attitudes influence behavior, here’s something that might blow your mind: the reverse relationship also happens – your actions significantly influence your subsequent attitudes. This bidirectional relationship has huge implications for organizational change and attitude management strategies. People really do come to believe what they’ve stood up for!

The James-Lange theory of emotion proposes that emotional experiences actually result from physiological responses rather than causing them – you’re happy because you smile, not the other way around. This suggests that behavioral changes might lead to attitude changes through what researchers call embodied cognition processes.

The foot-in-the-door phenomenon shows that people who agree to small requests become much more likely to comply with larger requests later. This happens partly because initial compliance creates attitude changes that support continued cooperation. Organizations seeking employee involvement in major initiatives might start with small requests that gradually build commitment and positive attitudes.

Role-playing effects demonstrate that when you first adopt new behavioral roles, it feels artificial, but gradually becomes internalized as genuine attitude change. Philip Zimbardo’s famous Stanford prison experiment showed how quickly people can internalize role-appropriate attitudes, with student volunteers genuinely adopting prisoner or guard mindsets within just days.

When people are first put into new social roles, they feel like they’re just acting the part. But after a while, role-specific behavior doesn’t feel forced anymore. In Zimbardo’s study, college students volunteered to spend time in a simulated prison. Some were guards, others were prisoners. For the first few days, volunteers were just playing their roles. But after a few days, the role-playing became internalized as real attitudes. The guards began truly believing the prisoners were inferior and started treating them badly. The prisoners broke down, rebelled, or became passively resigned. People began genuinely believing in the behaviors they were initially just “acting.”

Organizations can apply this through job rotation programs, temporary leadership assignments, and cross-functional team participation. These experiences help you develop more positive attitudes toward different organizational functions while building empathy and understanding across departments.

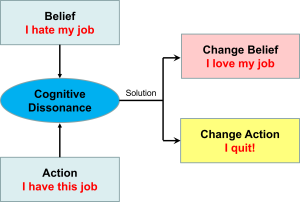

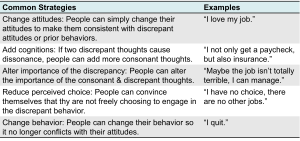

When Your Mind Fights Itself: Cognitive Dissonance Theory

Cognitive dissonance theory, developed by Festinger (1957), explains what happens when your thoughts and actions don’t match up. The theory proposes that you experience psychological discomfort when you hold inconsistent beliefs or when your actions contradict your attitudes, and you’ll work to reduce this discomfort through attitude or behavior change.

We act to reduce the mental discomfort (dissonance) we feel when two of our thoughts are inconsistent. Often, dissonance comes up when your actions contradict your existing attitudes, creating pressure to modify your attitudes to restore psychological consistency. Since you can’t change past behaviors, you typically resolve dissonance by adjusting your attitudes to align with what you’ve already done.

Consider this scenario: you invest significant time and money in professional development training but don’t feel like you’ve improved much. The inconsistency between your investment (behavior) and perceived outcome (cognition) creates dissonance that you might resolve by changing your perception – deciding that improvement actually did occur, even if you didn’t initially recognize it. The example shows: “I spent a lot of time and money on therapy and I don’t think I improved” creates significant dissonance. Changing your belief to “maybe I did get better” eliminates the discomfort.

This explains why employees who participate in change initiatives often develop more positive attitudes toward those changes, even if they initially opposed them. Active participation creates behavioral commitment that generates pressure for attitude alignment through dissonance reduction.

Organizations can use dissonance principles by encouraging your participation in decision-making, policy development, and change implementation. Such participation creates psychological ownership and commitment that enhance attitude change beyond what communication or incentives alone can achieve.

Why Should I/O Professionals Care About Attitudes?

You might be wondering, “This is all fascinating, but why should we actually study this stuff?” Industrial and organizational psychologists focus on job attitudes for several compelling reasons that reflect both practical and theoretical considerations.

Performance relationships represent the most obvious reason for studying job attitudes. To the extent that attitudes influence behavior – and particularly job performance – organizations have clear financial incentives to understand and manage employee attitudes effectively. While the attitude-performance relationship is more complex than initially assumed, substantial evidence shows meaningful connections between attitudes and various performance indicators. Let’s be honest – this is I/O psychology, so it’s ultimately about organizational effectiveness and, yes, money!

Humanitarian considerations motivate psychologists who want to improve work attitudes to benefit employees’ general well-being. Since work represents a major component of most people’s lives, and happiness and fulfillment are important life goals, improving workplace attitudes serves important human values beyond just organizational productivity concerns. The goal of life is happiness, and our jobs are a huge part of our lives.

Spillover effects suggest that work attitudes influence non-work aspects of life, including family relationships, physical health, and community involvement. Understanding how work attitudes affect broader life satisfaction helps justify organizational investments in attitude improvement while recognizing the social responsibilities employers have.

Predictive utility for various organizational outcomes makes attitude research valuable for practical decision-making. Attitudes help predict turnover, absenteeism, safety performance, customer satisfaction, and other outcomes that directly impact organizational effectiveness and costs.

Media Attributions

- Cognitive Schemata of Attitudes © Emmavt is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- ABCs of Attitudes © Jay Brown

- Types of Attitudes

- Theory of Planned Behavior © Robert Orzanna is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- The Influence of Internal Attitudes and External Influences on Behaviors © Jay Brown

- Stanford Prison Experiment © Eric Castro is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Cognitive Dissonance Resolution © Jay Brown

- Strategies for Reducing Cognitive Dissonance