11-2: Job Satisfaction

How We Discovered That Worker Happiness Matters: Historical Development

How We Discovered That Worker Happiness Matters: Historical Development

Picture this: it’s the 1920s, and most business leaders think workers are basically sophisticated machines that need fuel (wages) to operate efficiently. Then along comes a revolutionary thinker who changes everything we know about the workplace.

Job satisfaction represents a pleasurable, positive emotional state resulting from your evaluation of your job or job experiences. As an attitude, job satisfaction includes cognitive, affective, and behavioral components that influence how you think, feel, and act toward your work roles.

The story of job satisfaction research reflects our evolving understanding of employee psychology and organizational management. Elton Mayo introduced emotional concepts into mainstream American industrial psychology during the 1920s, marking a crucial turning point in recognizing that worker feelings and attitudes actually matter.

Mayo argued that factory work resulted in various negative emotions including anger, fear, suspicion, lowered performance, and increased illness, which contributed to labor union development and worker unrest. Before this recognition, psychologists and managers showed little interest in worker happiness, assuming that adequate wages would ensure employee satisfaction. The prevailing wisdom was simple: pay people enough, and they’ll be happy.

Then came groundbreaking research that changed everything. Hoppock’s 1935 survey of working adults in a small Pennsylvania town provided one of the first systematic investigations of job satisfaction. This study found that only 12% of workers could be classified as dissatisfied, with wide variations among individuals within the same types of jobs and systematic differences between different occupational categories. Professionals and managers showed higher satisfaction levels than unskilled manual laborers, suggesting that both job-related factors and individual differences influence satisfaction.

These early findings established patterns that still characterize job satisfaction research today: most employees report general satisfaction with their work, but there’s substantial variation both within and between different types of jobs. This variation has motivated decades of research into what causes job satisfaction and what results from it.

Here’s something that might surprise you: contemporary surveys show that overall job satisfaction rates have remained relatively stable over the past 50 years, with approximately 87% of Americans reporting that they like their jobs overall. However, satisfaction varies considerably across different job aspects, with employees generally more satisfied with work content than with rewards and advancement opportunities.

Most Americans like their jobs overall (87%). People are relatively satisfied with the nature of the work itself: how interesting it is (88%) and having contact with people (91%). However, people are less happy with rewards: pay (66%), benefits (67%), and chances for promotion (60%). When people say they’re satisfied, they often mean they’re not dissatisfied!

From the beginning, practitioners have viewed job satisfaction as an important driver of productivity (Organ, 1988), making it a central concern for organizational effectiveness and employee well-being.

The Building Blocks of Satisfaction: What Makes Work Satisfying?

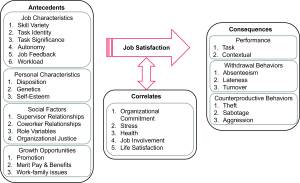

Research on job satisfaction can be organized into several key areas that help us understand both what causes satisfaction and what results from it. Think of it like a recipe – we need to understand the ingredients that go into job satisfaction before we can create the perfect work experience.

Your Job’s DNA: Job Characteristics and Satisfaction

Building on Hackman and Oldham’s Job Characteristics Theory (1976), research consistently demonstrates relationships between how jobs are designed and employee satisfaction. The five core job dimensions provide a framework for understanding how work structure influences satisfaction outcomes.

Skill variety involves how many different skills and talents your job requires, with greater variety typically associated with higher satisfaction. Jobs that use multiple employee capabilities provide opportunities for mastery and growth while reducing boredom and monotony. However, excessive variety can create stress and confusion, suggesting there’s an optimal rather than maximum variety level. Ask yourself: How many different skills do I need to perform my job?

Think about it this way: would you rather do the exact same task over and over all day, or have a variety of challenging activities? Most people prefer variety, but not complete chaos.

Task identity reflects how much your job involves completing whole, identifiable pieces of work rather than just small fragments. When you can see your complete contributions to organizational outcomes, you typically report higher satisfaction than when you perform only tiny parts of larger processes. Task identity provides meaning and purpose that enhance satisfaction beyond simple task completion. The question is: To what extent do I complete a “whole” piece of work instead of just a part?

Task significance represents how much your job impacts other people’s lives or work. When you understand how your contributions matter to others, you experience greater satisfaction than when you perceive your work as inconsequential. Organizations can enhance task significance by clarifying connections between individual jobs and organizational mission or customer outcomes. Consider: What kind of impact does my job have on the lives or work of others?

Autonomy encompasses freedom, independence, and discretion in scheduling work and determining procedures. Greater autonomy typically leads to higher satisfaction, though individual differences in autonomy preference moderate this relationship. Some people prefer clear structure and guidance, while others thrive with independence and self-direction. It’s about having freedom and independence of action.

Feedback involves how much your work activities provide clear information about your performance effectiveness. Regular, specific feedback helps you understand your performance levels while identifying improvement opportunities. Feedback satisfaction depends on both quantity and quality, with constructive, development-oriented feedback proving more satisfying than criticism or generic praise. Ask yourself: To what degree does my job provide clear information about my effectiveness?

Changes in these five factors alter the scope of a job – its complexity and challenge. Research shows positive relationships between employee perceptions of these job characteristics and job satisfaction, with correlations typically ranging from .30 to .40. These moderate correlations suggest that job characteristics represent important but not exclusive determinants of satisfaction.

Spector and Jex (1991) found that employees’ perceptions of job characteristics and job satisfaction are positively related (r = .30s to .40s). Additional research has shown that job structure and what the job provides affects job satisfaction. Work schedule and staffing are related to job satisfaction (Holtom, Lee, & Tidd, 2002). Concern about job security (Probst, 2003) and “daily hassles” are negatively related to job satisfaction (Hart, 1999).

It’s Not Just the Job, It’s You: Individual and Personal Characteristics

Here’s something that might challenge your thinking: research suggests that job satisfaction shows considerable stability over time, indicating that individual differences play important roles in determining satisfaction. Understanding these individual factors helps organizations recognize that satisfaction results from both situational and personal influences.

Staw and Cohen-Charash (2005) found that satisfaction is stable over time, suggesting individual differences play an important role. Affective disposition represents your tendency to respond to environmental situations in predetermined ways, essentially reflecting personality differences in emotional reactivity. If you have a positive affective disposition, you tend to experience higher job satisfaction across various work situations, while those with negative dispositions report lower satisfaction even in objectively favorable conditions. Affective disposition may account for up to 30% of the variance in job satisfaction measures.

This means some people are just naturally more positive about their work experiences, while others tend to find fault even in good situations. It’s like having built-in rose-colored glasses versus built-in pessimism filters.

Organization-based self-esteem (OBSE) measures how valuable you view yourself as an organization member. Higher OBSE typically correlates with greater job satisfaction, possibly because you feel more accepted and valued in your work role. OBSE represents a domain-specific form of self-esteem that may be more amenable to organizational influence than global self-esteem.

Genetic factors may play an important role (Arvey, Bouchard, Segal, & Abraham, 2006), though other evidence suggests that job satisfaction isn’t overly stable (e.g., Steel & Rentsch, 1997).

Age demonstrates generally positive relationships with job satisfaction, with older workers typically reporting higher satisfaction than younger employees. This pattern may reflect several mechanisms: dissatisfied workers may have left the workforce, older workers may have greater chances for fulfillment through seniority and advancement, or age may bring perspective that enhances appreciation for work benefits. In general, job satisfaction increases with age.

Gender shows inconclusive relationships with job satisfaction, with some studies finding differences and others reporting no significant gender effects. When differences emerge, they often reflect different priorities and values rather than inherent gender characteristics.

Race shows some patterns in satisfaction research, with whites generally reporting higher happiness levels in job satisfaction studies.

Cognitive ability shows a slight negative relationship between level of education and satisfaction. This counterintuitive finding raises the question: Why might higher education be associated with lower satisfaction? This may be due to elevated expectations that are harder to fulfill in actual work situations.

People Matter: Social Factors and Satisfaction

You’ve probably heard the saying “People don’t quit jobs, they quit bosses.” Well, research backs this up! Relationships with supervisors and coworkers represent important predictors of your satisfaction, reflecting the fundamentally social nature of most work environments. Quality interpersonal relationships can compensate for various job deficiencies, while poor relationships can undermine satisfaction even in otherwise favorable conditions. Think about a really “good” job you’ve had – relationships probably played a major role.

Supervisory relationships significantly influence satisfaction through leadership behaviors, communication quality, support provision, and fairness demonstration. When you perceive your supervisor as competent, caring, and fair, you typically report higher satisfaction than those with poor supervisory relationships. Effective supervision involves balancing task focus with relationship attention while adapting leadership style to individual employee needs.

Coworker relationships affect satisfaction through social support, cooperation, friendship, and team effectiveness. Positive coworker relationships provide emotional support during difficult periods while making work more enjoyable and meaningful. Conflict or competition among coworkers can create stress and reduce satisfaction even when other job aspects are favorable.

Organizational justice encompasses your perceptions of fairness in policies and procedures, influencing attitudes, behaviors, and performance across multiple domains. Justice perceptions include distributive justice (fairness of outcomes), procedural justice (fairness of processes), and interactional justice (quality of interpersonal treatment). All three forms of justice contribute to job satisfaction, with procedural justice often showing the strongest relationships. Employee perceptions of the fairness of policies and procedures affects attitudes, behaviors, and performance.

Room to Grow: Growth Opportunities and Satisfaction

Perceptions of potential for development and promotion significantly influence job satisfaction. If we perceive we’ll continue to make more money and get promoted, we’ll be satisfied with our jobs, at least to some extent. The availability of career advancement, skill development, and learning opportunities contributes substantially to employee satisfaction and retention.

But here’s where it gets complicated: sometimes opportunities for growth at work and in the family can conflict and become a source of stress. This tension is especially important for dual-earner families who must navigate competing demands between professional advancement and family responsibilities. Organizations that recognize and address these conflicts through flexible policies and support systems tend to achieve higher satisfaction levels.

How Do We Actually Measure Job Satisfaction?

You might be thinking, “This all sounds great in theory, but how do we actually measure something as subjective as job satisfaction?” Great question! Job satisfaction measurement involves several important considerations that influence research findings and practical applications.

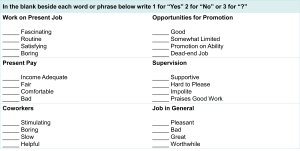

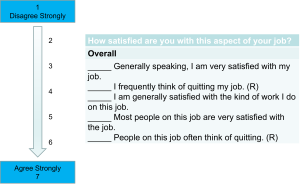

Overall versus facet satisfaction represents a fundamental measurement distinction. Overall satisfaction measures assess general attitudes toward jobs as a whole, while facet satisfaction measures examine attitudes toward specific job aspects such as pay, supervision, coworkers, work content, and advancement opportunities. You may be satisfied with some facets while being dissatisfied with others, creating complex satisfaction profiles that require nuanced interpretation. Overall job satisfaction is not the same as facet satisfaction. You can be satisfied with one facet yet dissatisfied with another.

The Job Descriptive Index (JDI) represents one of the most widely used facet satisfaction measures, assessing five dimensions: work content, pay, promotion opportunities, supervision, and coworkers. The JDI also includes a general satisfaction measure, enabling comparison between overall and facet satisfaction levels.

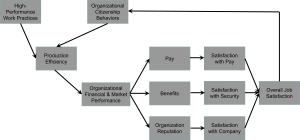

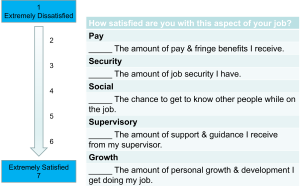

The Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS) uses Job Characteristics to measure five Job Facets that interact to create job satisfaction: Pay, Security, Social, Supervisory, and Growth satisfaction. The JDS includes an overall measure of satisfaction and happiness with one’s job, connecting job characteristics theory directly to satisfaction measurement.

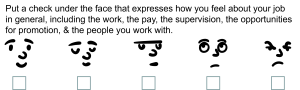

Other Overall Measures include the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire, which measures 20 different facets of job satisfaction, or can use a short form to measure overall job satisfaction. The Faces Scale measures the more emotional component of satisfaction using visual representations of facial expressions rather than written statements. This approach may capture emotional aspects of satisfaction that verbal measures miss while being appropriate for employees with limited literacy skills.

What Happens When People Are (or Aren’t) Satisfied? Performance Relationships

Now we get to the million-dollar question: does job satisfaction actually matter for performance? The relationship between job satisfaction and job performance represents one of the most extensively studied topics in industrial psychology, yet it remains more complex and conditional than initially assumed.

The question “Is the satisfied worker a productive worker?” has generated extensive research with nuanced findings. Task performance shows modest correlations with job satisfaction, with meta-analytic estimates ranging from .14 to .30 in most studies, though some recent analyses find correlations as high as .59. The relationship appears stronger for highly complex jobs (r = .52) and managerial positions than for routine or manual work, possibly because complex jobs provide greater opportunities for satisfaction to influence performance through motivation and effort. The correlation is higher for managers and others in highly complex jobs than non-managers.

Remember that although attitude is often the strongest predictor of behavior, other factors contribute as well. Cultures high on individualism and low on uncertainty avoidance have stronger satisfaction-performance relationships, suggesting cultural influences on this fundamental relationship.

Organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) demonstrate stronger relationships with satisfaction than task performance, with correlations typically ranging from .20 to .50. Organ (1988) suggests the mean correlation is about .30. OCBs represent voluntary behaviors that benefit organizations but aren’t formally required, making them more susceptible to attitude influences than mandated task performance. The causal relationship between satisfaction and OCBs continues to be debated in the literature.

Research demonstrates several specific satisfaction-performance connections. Barling, Kelloway, and Iverson (2003) found that satisfying jobs are linked to fewer occupational injuries, suggesting that satisfied employees may be more careful and safety-conscious. Harter, Schmidt, and Hayes (2002) demonstrated positive relations between employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction, productivity, profit, safety, and employee retention.

Several studies (LePine, Erez, & Johnson, 2002; Tang & Ibrahim, 1998) found that increased satisfaction is associated with increased organizational citizenship behavior. Judge, Thoresen, Bono, and Patton (2001) found a positive correlation of substantial magnitude (.30) between job satisfaction and task performance. Conte, Dean, Ringenbach, Moran, and Landy (2005) found that job satisfaction is associated with job analysis ratings: More satisfied employees give higher ratings for the frequency and importance of various tasks.

When People Check Out: Withdrawal Behaviors and Satisfaction

Job satisfaction demonstrates consistent negative relationships with various withdrawal behaviors, though these relationships are generally modest in magnitude. Understanding withdrawal behaviors helps organizations assess the costs of dissatisfaction while identifying intervention opportunities.

Absenteeism shows correlations with satisfaction ranging from -.15 to -.25, indicating that dissatisfied employees are somewhat more likely to be absent from work. However, context matters significantly: only 28% of employee time off results from personal illness, with significant portions attributed to family caregiving responsibilities, personal business, and other non-illness factors. Costs associated with aging loved ones exceed $12 billion per year, while costs associated with carpal tunnel syndrome (workers’ compensation) reach $60 billion annually.

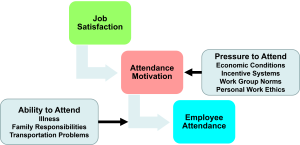

The relationship between satisfaction and absenteeism is captured in Steers and Rhodes’ (1978; 1990) Attendance Model, which shows that though job satisfaction is in the model, it doesn’t seem to play a direct role in predicting attendance. Other factors like ability to attend and motivation to attend serve as more immediate predictors.

Here’s a fascinating contemporary phenomenon: there are actually companies that generate excuse notes for $25 – customers just fill in the name and address for the doctor, dentist, or local government to list jury duty and a realistic-looking note will be generated. The website says it’s for entertainment purposes only and includes testimonials about the effectiveness of the notes. These can even be used to get out of gym membership contracts!

Tardiness/Lateness shows recent meta-analytic relationships around r = -.21, with chronic lateness significantly predicted by job satisfaction (r = -.39). Williams, Gavin, and Williams (2006) found that satisfaction with pay is moderately associated with turnover intentions (.31) and actual turnover (.17). Johns (1997) found that satisfied employees are less likely to be absent from work. Kozlowski, Kirsch, and Chao (1997) found that satisfied employees are less likely to be late for work.

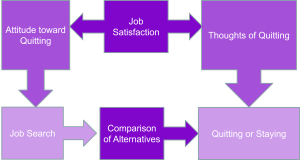

Turnover shows relationships with satisfaction ranging from -.20 to -.30, making satisfaction an important but not exclusive predictor of voluntary turnover. The costs of turnover vary by job level and organization, with estimates suggesting replacement costs of approximately $3,500 for employees paid $8 per hour (according to Society for Human Resource Management), or 1.5 to 2.5 times monthly salary for higher-level positions. Job satisfaction is seen as a trigger to decisions about turnover.

Two main factors predict turnover: (1) perceived ease of movement and (2) perceived desirability of movement. Only the second factor seems to be reflected in job satisfaction, though desirability can be influenced by other things such as a great offer that’s too good to pass up or relocation opportunities.

The unfolding model (Lee & colleagues) suggests that “shock to the system” (e.g., unsolicited job offer, change in marital status, transfer, merger) propels turnover. A recent study found that half of voluntary turnover was due largely to family reasons or an unsolicited job offer, highlighting the complexity of turnover decisions beyond simple job dissatisfaction.

Functional turnover represents the loss of bad workers (which can actually be beneficial), while dysfunctional turnover represents the loss of productive workers (which is costly). Hom and Griffeth’s (1991) Modified Model of Turnover provides a comprehensive framework for understanding these different types of departure decisions.

When Dissatisfaction Turns Destructive: Counterproductive Behaviors

Counterproductive behaviors represent any behaviors that bring, or are intended to bring, harm to an organization, its employees, or stakeholders. These are also known as antisocial or dysfunctional behaviors.

Frustration results from dissatisfaction leading to behaviors such as sabotage, blackmail, and bribery. Most common for younger, dissatisfied workers, correlations between job satisfaction and counterproductive behaviors range from -.10 to -.25. However, the relationship may depend on individual differences of the employee, suggesting that personality factors moderate how dissatisfaction translates into harmful behaviors.

Beyond the Workplace: Other Outcomes of Job Satisfaction

Health and well-being represent important consequences of job satisfaction. Job dissatisfaction can lead to stress which is unhealthy, creating both physical and psychological health problems. The relationship between work attitudes and health outcomes demonstrates the importance of job satisfaction beyond simple organizational effectiveness measures.

Life satisfaction shows complex relationships with job satisfaction through three competing theoretical perspectives:

The Spillover Hypothesis suggests that satisfaction in one area of life spills over to others. Under this model, job satisfaction would enhance overall life satisfaction and family relationships.

The Compensation Hypothesis proposes that satisfaction in one area of life can compensate for dissatisfaction in another. According to this perspective, individuals might maintain overall well-being through high family satisfaction even when experiencing job dissatisfaction.

The Segmentation Hypothesis argues that satisfaction in one area of life is unrelated to satisfaction in other areas of life. This perspective suggests that work and non-work satisfaction operate independently.

Several researchers (Warr, 1999; Wright & Cropanzano, 2000) have found positive associations between job satisfaction and general life satisfaction and feelings of well-being, providing support for the spillover hypothesis. This research demonstrates that improving job satisfaction serves both organizational and humanitarian purposes by enhancing overall quality of life.

Media Attributions

- Evaluating Emotional Responses © Mohamed Hassan is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Job Satisfaction Model © Jay Brown

- Job Satisfaction Measurement © Jay Brown

- Job Description Index

- Job Diagnostic Survey Overall © Jay Brown

- Job Diagnostic Survey © Jay Brown

- Faces Scale © Jay Brown

- Withdrawal Behaviors © Jay Brown

- Hom & Griffeth’s Modified Turnover Model adapted by Jay Brown