12-1: Stress

You’re working at a job where you constantly feel like you’re drowning in tasks, your supervisor gives you about as much direction as a broken GPS, you’re constantly worried about layoffs, and you can’t remember the last time you had a peaceful evening with family because work stress follows you home like a shadow. Now add to this nightmare the joy of working with a dysfunctional team where nobody talks to each other except to argue, conflicts pop up like weeds, and the unspoken rule seems to be “whoever works themselves into the ground wins.” Sound absolutely exhausting?

Now flip the script and imagine the complete opposite: a workplace where you feel genuinely supported, challenged in ways that make you grow (not ways that make you cry), secure in your position, and actually able to maintain some semblance of balance between work and the rest of your life. Plus, you’re working with a team that actually functions like a team — you share clear goals, communicate like adults, and everyone’s got each other’s backs. Which scenario would you choose? I’m guessing it’s a no-brainer.

Here’s something that might surprise you: the difference between these two experiences isn’t just about luck or stumbling onto the “right” company. It’s about understanding what we call worker well-being — and trust me, it’s way more complicated and important than you might think.

Worker well-being isn’t just about whether you’re happy at work or how well you manage your personal stress. It’s actually a critical domain within industrial-organizational psychology that examines the physical, psychological, and social health of employees in organizational contexts. And here’s the key part that many people miss — your well-being at work is deeply connected to the people around you and how your team functions. You’re not an island at work; you’re part of an ecosystem.

Occupational health psychology (OHP) is this fascinating interdisciplinary area that focuses on keeping workers healthy and safe. It tackles major issues like how work stress affects your physical and mental health, how you balance work and family life, workplace violence, and interventions designed to improve and protect worker health. What’s becoming increasingly clear from research is that your well-being is significantly influenced by group dynamics, team processes, and the social context of work.

Want a statistic that’ll make you sit up and pay attention? The World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization did a study showing that exposure to long working hours literally kills people — they found that it caused an estimated 745,000 workers to die from heart disease and stroke in 2016 alone (Pega et al., 2021). These weren’t just numbers on a spreadsheet — those were real people whose work environments literally cost them their lives. That’s not dramatic language; that’s cold, hard data showing why we need to take workplace well-being seriously, including the critical role of healthy team functioning.

So what exactly does worker well-being include? It’s like a multi-layered cake that encompasses stress management, work-family balance, job security, workplace safety, organizational support systems, and — as you’ll discover throughout this module — group dynamics and team effectiveness. The field draws from psychology, medicine, sociology, and organizational behavior to develop evidence-based interventions that actually work to create healthy work environments.

Here’s why you should care about all this: whether you end up as a manager, employee, consultant, or entrepreneur, you’re going to spend roughly a third of your adult life at work. Understanding how individual factors and group processes can either support or completely undermine your health and happiness isn’t just academic knowledge — it’s essential survival skills for creating workplaces where people can actually thrive rather than just survive.

Understanding Stress in the Workplace

Let’s start with stress — something you’ve probably experienced whether you’re working, studying, or just trying to adult in general. You might think you know what stress is, but let’s get really precise about it because the details matter. Stress can be defined as the process by which you perceive and respond to certain events, called stressors, that you appraise as threatening or challenging.

Here’s what’s really interesting about stress: it’s not always the villain we make it out to be. When you perceive stressors as challenges rather than threats, they can actually motivate you and enhance your performance. Think about how a looming deadline might help you laser-focus and finally get things done, or how a little friendly competition can bring out your best effort. That’s stress working for you rather than against you.

But when you perceive stressors as threats — when they feel overwhelming, uncontrollable, or like you’re being asked to move mountains with a teaspoon — they can seriously harm your physical and psychological health. The difference between “good stress” and “bad stress” often comes down to how you interpret what’s happening to you.

SIOP Top 10 Trends: Contemporary Workplace Well-Being Challenges

The Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology identifies several critical trends that directly impact worker well-being:

Trend #7: Stress & Burnout

With high workloads and minimal time off, workers are stressed to the point that they can no longer properly fulfill their job roles and maintain a healthy, balanced lifestyle. Burnout represents the state of being overwhelmed by stress to the point of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion. This isn’t just about feeling tired — burnout fundamentally impairs your ability to function effectively at work and maintain well-being.

Trend #5: Caring for Employee Well-Being

This trend highlights what workers are facing and ways organizations can identify the right resources to supply their teams. With psychological safety becoming more important, how can organizations better understand what that means and incorporate it into their culture and environment? How can employers safeguard employees’ well-being and optimally care for them?

Trend #9: Employer’s Role in Employees’ Mental Health

Employees’ mental health has been an issue for a long time and has been exacerbated by the pandemic. Organizations play a crucial role in safeguarding employees’ mental health. What can and will organizations do about the employee mental health crisis, if anything at all?

Group Influences on Stress Perception

You might be thinking, “Okay, but what does my team have to do with my stress levels?” Actually, pretty much everything. The social context of work significantly influences how you perceive and respond to stressors — your teammates are like the lens through which you see your work challenges.

Group norms — those shared expectations about what’s considered appropriate behavior in your workplace — can either crank up your stress levels or help dial them down. Have you ever worked somewhere where everyone seemed to be in some kind of unofficial competition over who could work the most ridiculous hours? That’s what we call a descriptive norm (what most people actually do) that can create a stressful environment even if no official policy requires you to sacrifice your evenings and weekends to the work gods.

Prescriptive norms, on the other hand, suggest what people should do. When your team has healthy prescriptive norms about maintaining work-life boundaries — like actually meaning it when they say “don’t check email after 6 PM” — your individual stress levels often decrease dramatically.

Here’s a fascinating phenomenon that might explain some of your work experiences: social facilitation effects show that your performance on tasks can be either improved or completely tanked depending on who’s around you and how good you are at what you’re doing (Zajonc, 1965). If you’re performing something you’re already good at, having colleagues around might boost your performance. Ever notice how you might type faster when your supervisor is nearby, or how you play better pool when friends are watching (assuming you’re already decent at pool)?

But here’s the flip side — if you’re struggling with a difficult task, the presence of others can increase your stress and actually make your performance worse. It’s like your brain gets stage fright and forgets how to function properly, leading to additional stress on top of whatever you were already dealing with.

The Stress-Performance Relationship

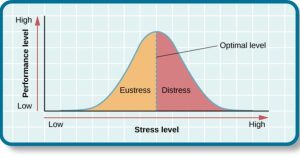

The relationship between stress and performance follows a well-established pattern that researchers call the stress-performance curve. Picture an upside-down U — this is going to be important for understanding your work life.

As stress levels increase from low to moderate, your performance typically improves. This is what researchers call “eustress” or positive stress. You know that feeling when you have just enough pressure to focus and get things done efficiently? When you’re in the zone and everything seems to click? That’s eustress in action, and it’s actually a good thing.

At the optimal level — right at the top of that upside-down U — your performance reaches its peak. You’re firing on all cylinders, thinking clearly, and getting stuff done. But here’s where things get tricky: if stress exceeds this optimal level, it enters what we call the distress region, where it becomes excessive and debilitating, leading to performance decline. Ever felt so overwhelmed that you couldn’t think straight, even about simple things? That’s distress taking over.

Here’s where your team becomes absolutely crucial: group factors can dramatically shift this curve. Supportive teams can help you handle higher stress levels effectively, essentially moving your optimal performance point higher. It’s like having a good spotter at the gym — you can lift more weight safely. But dysfunctional groups can push you into distress much more quickly, like having teammates who keep adding weight to your bar while you’re trying to lift.

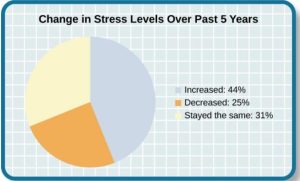

The statistics on workplace stress are pretty sobering. Nearly half of U.S. adults say their stress levels have increased over the last five years, with marked increases observed across all demographic categories — gender, age, race, education level, employment status, and income (American Psychological Association, 2019). This isn’t just affecting “other people” — these findings suggest that workplace stress has become this pervasive issue affecting diverse segments of the workforce, including you, your future colleagues, and potentially your future employees.

The Physiological Basis of Stress

Understanding what stress actually does to your body provides crucial insight into why workplace conditions matter so much for your health. Let’s talk about what’s happening inside you when you’re stressed — and trust me, it’s more dramatic than most action movies.

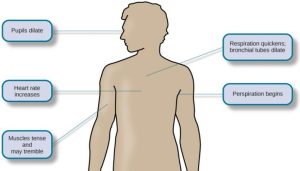

Walter Cannon’s research identified the stress response as triggering an outpouring of stress hormones, particularly cortisol, from your adrenal glands (Cannon, 1932). When you’re stressed, your sympathetic nervous system essentially hits the panic button: your heart rate increases, your breathing speeds up, energy gets diverted from digestion (goodbye, normal lunch break), pain gets dulled, and sugar and fat get released from storage. Your body is basically preparing for action — any kind of action.

This fight-or-flight response was remarkably adaptive throughout human evolution. Imagine needing to run from a predator or fight for survival — this response could literally save your life. Your ancestors who had strong stress responses were more likely to survive and pass on their genes. However, the modern workplace often creates conditions of chronic stress, where your body’s adaptive mechanisms become maladaptive. It’s like having your car’s emergency flashers stuck in the “on” position — what’s supposed to be a helpful temporary signal becomes an annoying drain on your system.

Here’s where team dynamics become absolutely crucial: working in a psychologically unsafe team environment where you constantly fear criticism, rejection, or conflict can keep your stress response chronically activated. Your body doesn’t distinguish between running from a saber-toothed tiger and dealing with a toxic team meeting — it responds the same way to both situations.

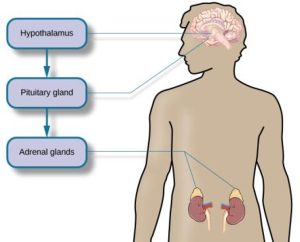

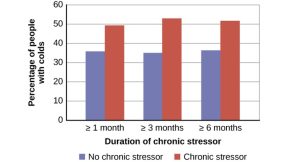

Research has demonstrated clear connections between workplace stress and immune function. Studies show that people reporting chronic stressors lasting more than one month are significantly more likely to develop illnesses compared to those without chronic stressors (Cohen et al., 1998). Your hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis plays a central role in these processes. Think of it as your body’s alarm system: your hypothalamus activates your pituitary gland, which in turn activates your adrenal glands to increase cortisol secretion. It’s like having your body’s alarm system constantly blaring — and toxic group dynamics can be a primary trigger for keeping this alarm stuck in the “on” position.

Models for Understanding Workplace Stress

You might be wondering, “How do researchers actually study and explain this stress stuff?” Great question! Several theoretical models have been developed to explain how workplace conditions contribute to stress and its outcomes. These models provide frameworks for understanding how stress develops, why it affects people differently, and how seemingly minor stressors can produce major stress reactions.

The General Adaptation Model

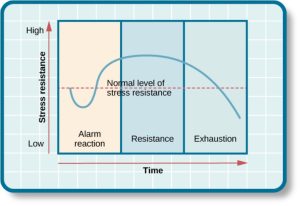

Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome represents one of the earliest comprehensive models for understanding stress responses (Selye, 1956). Think of it as a three-act play describing your body’s response to stress — and like many plays, it doesn’t have a happy ending if it goes on too long.

Act I: The Alarm Stage involves your initial reaction to stressors, characterized by increased heartbeat, decreased muscle tone and blood pressure, followed by a rebound reaction. This is your body’s “Oh no, something’s happening!” response. Your body is basically hitting the panic button and mobilizing all available resources.

Act II: The Adaptation/Resistance Stage is where your body mobilizes resources to defend itself against ongoing stressors. You’re essentially running on stress hormones to keep going. You might feel like you’re managing okay during this stage, but you’re actually using up your reserves like crazy. It’s like running your car on the emergency spare tire — it works for a while, but it’s not sustainable.

Act III: The Exhaustion Stage occurs when continuing stress results in the depletion of your adaptive resources, potentially leading to illness or breakdown. This is when your body basically throws up its hands and says, “I can’t keep this up anymore.” The system crashes.

Here’s where group factors become really important: supportive teams can help you stay in the adaptation stage longer, essentially giving you more resilience and keeping you from burning through your reserves as quickly. Think of good teammates as people who help you carry the load. Conflicted or dysfunctional groups, however, can accelerate your movement toward exhaustion by adding extra weight to what you’re already carrying.

The Life-Change Model and Social Readjustment Rating Scale

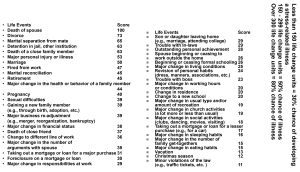

The Life-Change Model proposes something that might actually surprise you: all changes in your life, whether large or small, desirable or undesirable, can act as stressors (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). This model measures stress potential using the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), which quantifies stress in terms of “life change units.”

The SRRS provides specific scores for major life events, recognizing that the accumulation of small changes can prove just as powerful as major stressors in affecting your well-being. Here are key life events and their stress scores:

Major Life Events and Stress Scores:

Notice how even positive events like marriage (50 points) and pregnancy (40 points) contribute to your stress load. Getting a promotion, moving to a new apartment, and starting a new relationship might all be positive changes, but they still require adaptation and contribute to stress accumulation.

Group changes — such as team restructuring, new team members, or changes in group leadership — also contribute to this stress accumulation, even when the changes are ultimately positive. Cultural differences exist in how different groups rank these stressors, highlighting the importance of context in stress appraisal.

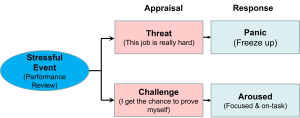

The Transaction Model

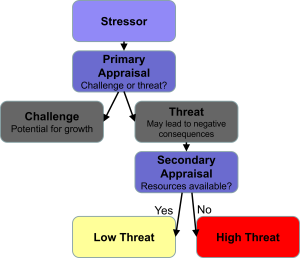

The Transaction Model represents a more sophisticated approach that recognizes stress as residing neither solely in you nor in the situation, but rather in the transaction between the two (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). This model emphasizes your subjective, cognitive interpretation of stressful events and life changes. In other words, it’s not just what happens to you — it’s how you think about what happens to you.

How you appraise events significantly influences both the amount of stress you experience and the effectiveness of your coping responses. When you perceive stressors as challenges, they can have positive effects, arousing and motivating you to overcome obstacles. However, stressors can also threaten important resources such as your job status, security, deeply held beliefs, and self-image.

Group dynamics play a crucial role in this appraisal process. The same looming deadline might be perceived as an exciting challenge in a supportive team environment or as an overwhelming, impossible threat in a conflicted, under-resourced team. Your teammates essentially help you interpret whether something is a manageable challenge or a threat that’s going to destroy you. They’re like your stress interpreters.

21st Century Organizational Changes Creating New Stressors

The modern workplace has undergone dramatic transformations that create new categories of stressors not experienced by previous generations of workers:

Technology-Related Stressors: Constant connectivity through smartphones and email creates expectations for 24/7 availability. The boundary between work and personal time has become increasingly blurred as technology enables work to follow you everywhere.

Organizational Restructuring: Frequent mergers, acquisitions, downsizing, and reorganizations create ongoing uncertainty and job insecurity. The traditional model of long-term employment with a single organization has largely disappeared.

Globalization Effects: Working with teams across multiple time zones, cultural differences in communication styles, and pressure to be available during off-hours to accommodate international colleagues.

Economic Uncertainty: Concerns about job security, healthcare benefits, retirement planning, and economic stability create background stress that affects daily work experiences.

Skills Obsolescence: Rapid technological change means skills can become outdated quickly, creating pressure for continuous learning and adaptation while working full-time.

Gig Economy Pressures: Increase in contract work, temporary positions, and multiple job arrangements that lack traditional benefits and security.

These 21st century changes interact with traditional workplace stressors to create more complex and demanding work environments that require new approaches to stress management and organizational support systems.

Contemporary Stress Models

Modern research has developed additional models that provide even more nuanced understanding of workplace stress mechanisms. The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model suggests that stress occurs when job demands exceed your available resources (Karasek & Theorell, 1990). High workloads combined with low levels of resources are related to job strain, with heavy job demands predicting emotional exhaustion while resources such as autonomy are positively related to feelings of accomplishment and negatively related to physical symptoms.

Think of it this way: imagine you’re trying to fill a bucket that has holes in it. Job demands are like water flowing into the bucket, while job resources are like having enough buckets, patches for the holes, or help carrying the water. When demands exceed resources, you’re in trouble — the bucket overflows and you’re left standing in a puddle of stress.

Group resources are particularly important in this model. Team support, effective communication, shared decision-making, and collaborative problem-solving all serve as resources that can buffer against job demands. It’s like having teammates who help you carry buckets and patch holes. Conversely, group demands such as interpersonal conflict, role ambiguity within the team, and poor group communication add to your overall demand load — they’re like extra holes in your bucket.

The Conservation of Resources (COR) Model proposes that you work to acquire and maintain resources you may need to ward off stress (Hobfoll, 1989). Resource loss plays a critical role in the stress process, making the prevention of resource loss key to both stress prevention and post-stress intervention strategies. Group membership can either contribute to or drain your resource pool depending on the quality of group functioning. Good teams add to your resources; bad teams are like resource vampires that suck them dry.

Media Attributions

- Work-Related Stress © CIPHR Connect is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Good Stress? © OpenStax is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Changes in Stress © OpenStax is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Fight or Flight Response © OpenStax is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- HPA Axis © OpenStax is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Stress Related to Illness © OpenStax is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- General Adaptation Syndrome © OpenStax is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Social Readjustment Rating Scale

- Stress Appraisal adapted by Jay Brown

- Stress Appraisal Process adapted by Jay Brown