12-4: Job Loss

Job loss represents one of the most significant stressors you can experience, with profound implications for your psychological and physical well-being. Understanding why employment holds such importance helps explain the devastating effects of job loss on individual functioning and family systems. It’s not just about the money — though that’s certainly part of it.

Group Aspects of Job Loss

Team relationships significantly influence the experience of job loss in ways that might surprise you. When layoffs affect entire teams, members may provide mutual support that helps buffer the stress of unemployment. There’s something about shared adversity that can bring people together — you’re all in the same boat, facing similar challenges.

However, when layoffs are selective within teams, the dynamics become much more complicated. Remaining members may experience survivor guilt and increased workload stress, while those laid off may feel particularly isolated and singled out. Ever heard someone say, “Why them and not me?” after layoffs? That’s survivor guilt, and it can be psychologically brutal for those who keep their jobs.

Group identity also plays a crucial role in job loss adjustment. Individuals whose identity is strongly tied to their team or work group may experience more severe psychological effects when that group membership is suddenly severed. Think about how athletes describe losing their team identity when they retire, or how military personnel struggle with losing their unit identity. When your sense of self is wrapped up in being part of a particular team, losing that team membership can feel like losing part of yourself.

The Importance of Employment

Employment provides multiple critical functions beyond just financial compensation, and understanding these helps explain why job loss is so devastating. Sure, jobs provide financial means for maintaining desired lifestyles and meeting basic needs — paying rent, buying groceries, keeping the lights on. But that’s just scratching the surface.

Jobs create time structure for your daily and annual activities, offering predictability and routine that support psychological well-being. Without work, many people struggle with how to structure their days. Ever noticed how weekends can feel aimless sometimes? Imagine that feeling extending indefinitely.

Employment provides opportunities to use learned skills and develop new competencies, contributing to personal growth and professional identity. Team membership is a crucial component of this benefit — jobs offer social interactions and collaborative relationships that extend beyond family networks. For many people, coworkers provide important social connections and friendships.

Additionally, employment provides purpose and meaning to life while conferring social identity and prestige within communities. When people ask “What do you do?” they’re really asking “Who are you?” Your job often becomes a significant part of how you see yourself and how others see you.

Psychological Effects of Unemployment

Research consistently demonstrates that unemployment creates substantial psychological distress, and the evidence is overwhelming. The psychological health of unemployed workers is significantly poorer than that of employed workers, with this poorer health resulting from (rather than causing) unemployment (Wanberg et al., 2005). Recovery of employment typically leads to improvement in psychological well-being, supporting the causal relationship between job loss and mental health problems.

Recent research on job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic has provided new and concerning insights into unemployment’s psychological effects. A large-scale study of over 58,000 Norwegian parents found that psychological distress increased across all employment groups during the pandemic, but job loss had particularly severe effects (Riise et al., 2023). Specifically, those who lost their jobs experienced psychological distress increases of 1.24 standard deviations above pre-pandemic levels, compared to 0.47 for those with no employment change. To put that in perspective, that’s a massive difference — like the difference between feeling stressed and feeling completely overwhelmed.

Additionally, a longitudinal U.S. study found that income or job loss during the early pandemic (March-August 2020) was associated with elevated psychological distress that persisted for nearly two and a half years, with affected individuals showing 1.09 to 1.11 times higher distress scores in 2021 and 2022 (Ringlein et al., 2024). This isn’t just temporary stress — job loss creates lasting psychological wounds.

The COVID-19 pandemic also revealed important demographic disparities in job loss effects that highlight existing inequalities. Employment insecurity was disproportionately concentrated among Hispanic workers (54.3%), Black workers (60.6%), women (55.9%), young adults aged 18-29 (57.0%), and those without college degrees (62.7%) (Lee et al., 2021). These groups also experienced more severe mental health consequences, with Hispanic workers showing particularly elevated depression rates following employment insecurity.

Losing employment often results in depression, insomnia, irritability, lack of confidence, inability to concentrate, and general anxiety. These effects extend beyond you to affect family members and social networks — job loss doesn’t happen in isolation. The loss of team relationships and daily social interaction compounds these effects, as former colleagues may represent a painful reminder of loss or may simply drift away due to changed circumstances. It’s like losing your job and your social network at the same time.

Recent Trends in Job Loss

Several contemporary factors are reshaping the landscape of employment insecurity, creating new forms of job-related stress:

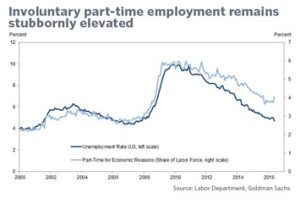

Underemployment Concerns: Questions about whether policy changes like healthcare legislation might lead to increased part-time work as employers seek to avoid benefit obligations. However, recent data shows that the number of Americans involuntarily working part-time fell by 707,000 to 3.6 million — the lowest level in 21 years as of 2022.

Immigration and Job Competition: Debates about whether immigration affects job availability for domestic workers, though economic research generally shows complex relationships rather than simple displacement effects.

Outsourcing to Lower-Cost Countries: Continued pressure from global competition leading organizations to move production and services to countries with lower labor costs, affecting manufacturing and increasingly service sector jobs.

Downsizing and Organizational Restructuring: Ongoing corporate efforts to reduce costs through workforce reductions, often targeting middle management and administrative positions.

Technology-Driven Changes: Automation and artificial intelligence creating demand for fewer but more skilled workers in many industries, while eliminating routine jobs across sectors.

These trends create ongoing uncertainty about employment security that affects worker well-being even among those currently employed, as people worry about future job stability and the need for continuous skill development.

Underemployment and Well-Being

While much attention focuses on unemployment, underemployment — working fewer hours than desired or in positions below your skill level — also significantly impacts psychological well-being. Research shows that underemployed workers experience psychological distress levels between those of adequately employed and unemployed workers, but the effects are often overlooked because these individuals are technically employed (Bell & Blanchflower, 2019).

This is particularly relevant in today’s gig economy, where many people cobble together part-time jobs or work in positions that don’t utilize their skills or education. You might be working, but if you’re a college graduate working retail when you want to be in your field, or if you’re only getting 15 hours a week when you need 40, you’re likely experiencing underemployment stress.

Studies using longitudinal data demonstrate that transitioning from full-time employment to underemployment predicts increased psychological distress, while moving from underemployment back to full-time work reduces distress levels (Bell & Blanchflower, 2019). The combination of working fewer than 30 hours per week while preferring more hours creates the greatest psychological distress among employed individuals. Importantly, these negative effects appear to be entirely reversible when workers transition out of underemployment — there’s hope for recovery.

Team factors play crucial roles in underemployment experiences. When teams lack cross-training or flexible coverage systems, individual workers may be forced into reduced hours during slow periods. Conversely, teams that can redistribute work effectively may help prevent underemployment by maintaining consistent hours for all members. Additionally, the social support available from team members can buffer some of the psychological effects of reduced work hours, while social comparison within teams (seeing colleagues work full-time while you cannot) may exacerbate distress.

Media Attributions

- Worried Man © Unknown adapted by Copilot is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Involuntary Part Time Employment © U.S. Labor Department

- EEOC Seal © U.S. Government is licensed under a Public Domain license