13-1: How Groups Affect Us

Ever notice how you act totally different when you’re in a group versus when you’re alone? Maybe you’re the type who’ll speak up confidently in a small study group but suddenly turn into a mouse in a packed lecture hall. Or perhaps you’ve been part of a team where everyone seemed smart individually, but somehow together you made decisions that were… well, let’s just say not your finest moment.

Ever notice how you act totally different when you’re in a group versus when you’re alone? Maybe you’re the type who’ll speak up confidently in a small study group but suddenly turn into a mouse in a packed lecture hall. Or perhaps you’ve been part of a team where everyone seemed smart individually, but somehow together you made decisions that were… well, let’s just say not your finest moment.

Welcome to the wild, fascinating, and sometimes downright weird world of group dynamics!

Here’s the thing about group behavior – it’s one of the most mind-bending areas in all of psychology because it shows us just how much other people mess with our thoughts, feelings, and actions without us even realizing it. Think about it: you probably check your phone more when you see others doing it, laugh at jokes that aren’t even funny when everyone else is cracking up, or find yourself working way harder (or sometimes way less hard) when you’re part of a team.

But here’s where things get really interesting – and honestly, a bit scary. Throughout history, groups have been responsible for some of humanity’s greatest achievements AND its most devastating failures. The same psychological forces that help teams land rockets on Mars can also lead perfectly normal people to make absolutely terrible decisions.

Let me tell you about something that happened during the Vietnam War that’ll blow your mind and show you just how powerful group influence can be. It’s called the My Lai Massacre, and it’s a stark reminder that understanding group dynamics isn’t just some academic exercise – it’s essential knowledge for anyone who wants to work effectively with others while keeping their moral compass intact.

On March 16, 1968, American soldiers killed hundreds of innocent people in a Vietnamese village called My Lai. When one of the participants, Paul Meadlo, was interviewed later, he described the events in a chillingly matter-of-fact way. When Lieutenant William Calley ordered his men to shoot everyone in the village, Meadlo said: “So I started shooting, I poured about four clips into the group… Men, women, and children… and babies.”

Now here’s what’s really disturbing: not one soldier refused to participate or spoke up against the killings. Could they all have been psychopaths? Highly unlikely. When asked why he participated, Meadlo said he was following orders and that it had seemed like “the right thing to do” at the time. His explanation suggested that pretty much anyone in that situation would’ve done the same thing.

That’s the power of group influence, and it’s something you absolutely need to understand.

Theoretical Foundations of Group Behavior

Let’s start with the basics. When psychologists talk about social influence, they’re describing something you experience every single day: how other people change your behavior, thoughts, and feelings just by being around. It’s not manipulation or mind control – it’s just a fundamental part of being human.

The building blocks of this influence are norms – those unwritten rules that every group develops about what’s okay and what’s not. You’ve been navigating norms your whole life, probably without thinking about it. In your family, maybe the norm is that everyone helps clean up after dinner. In your friend group, there might be an unspoken rule about not dating each other’s exes. At work, you might discover that people always stay a few minutes late or that “casual Friday” actually means “business casual Friday.”

Here’s where it gets interesting: there are actually two different types of norms, and they work in completely different ways.

Descriptive norms are about what most people actually do. They answer the question, “What’s normal here?” If you walk into a library and see everyone whispering, that’s a descriptive norm telling you how people typically behave in that space. Violate a descriptive norm and people might think you’re weird or unusual, but that’s about it.

Prescriptive norms, on the other hand, are about what people should do – they carry serious moral weight. These are the “right” and “wrong” behaviors that groups care deeply about. Violate a prescriptive norm and you might find yourself kicked out of the group entirely. People will see you as dysfunctional or bad.

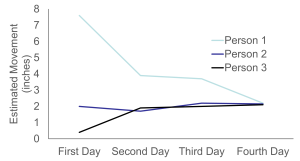

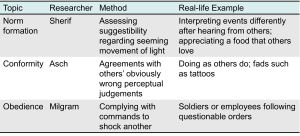

Want to see norm formation in action? Check out this amazing experiment by Sherif (1935). He put people in a completely dark room and showed them a tiny point of light. Because of how our eyes work (something called the autokinetic phenomenon), the light appeared to move even though it was perfectly still. When people judged the movement alone, their estimates were all over the place. But when they made judgments in groups, something incredible happened – their estimates started converging toward a group average.

What’s wild about this is that there was no “right” answer, yet the group created one anyway! This shows how powerfully we’re driven to create shared reality with others, even when we’re dealing with something completely ambiguous. The norms that emerged in these groups were so strong that people stuck with them even when they later made judgments alone. The group had literally changed how they saw the world.

Conformity and Obedience

Now let’s talk about one of the most famous and frankly unsettling discoveries in social psychology: how easily we conform to group pressure, even when we know the group is dead wrong.

Conformity is basically adjusting your behavior or opinions to match what the group is doing. You do this all the time – wearing certain clothes, using particular slang, laughing at jokes everyone else finds funny. Most conformity is harmless and actually helpful for getting along with others. But sometimes it can lead us seriously astray.

There’s this Japanese proverb that says, “The stake that sticks out gets hammered down.” In other words, standing out often goes hand in hand with criticism. And boy, did Solomon Asch prove this in one of psychology’s most elegant and disturbing experiments.

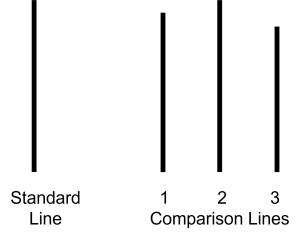

Picture yourself as a participant: you’re sitting at a table with several other people, and your task seems ridiculously simple. The experimenter shows you a line, then shows you three comparison lines of obviously different lengths. All you have to do is say which comparison line matches the original. Easy, right?

Here’s the twist that’ll make your jaw drop: everyone else at the table is actually working with the experimenter, and they’ve been told to give the same wrong answer. So when it’s your turn, you’ve just heard five people confidently give an answer that your eyes tell you is clearly incorrect. What do you do?

If you’re like most people, you’ll probably give the wrong answer too, at least some of the time. In Asch’s (1956) studies, people conformed to the obviously incorrect group consensus about one-third of the time. Think about that – these weren’t matters of opinion or ambiguous situations. The right answer was literally staring everyone in the face, yet the pressure to go along with the group was so strong that intelligent people abandoned the evidence of their own eyes.

You might be thinking, “Well, I’d never do that.” But before you get too confident, consider that conformity increases under exactly the conditions you’re most likely to encounter in real life:

When you’re feeling incompetent or insecure, when the group has at least three people, when the group is unanimous, when you admire the group’s status and attractiveness, when others in the group observe your behavior, and when your culture strongly encourages respect for social standards.

The psychology behind conformity operates through two main pathways, and understanding them can help you recognize when it’s happening to you.

Normative social influence is basically about fitting in – you go along with the group because you want to be liked and accepted, not because you think they’re right. You’ve probably experienced this when you’ve applauded for a performance you didn’t enjoy or nodded along with opinions you didn’t share.

Informational social influence is different – it happens when you genuinely think the group might know something you don’t. This is actually pretty rational in many situations. If you’re new to a job and everyone else is doing something a certain way, it makes sense to assume they have good reasons. The problem comes when we rely on this strategy in situations where the group might be just as clueless as we are.

Obedience takes social influence to a much more extreme level. While conformity is usually subtle and indirect, obedience involves direct commands from authority figures. And as Stanley Milgram’s famous experiments showed, the results can be absolutely terrifying.

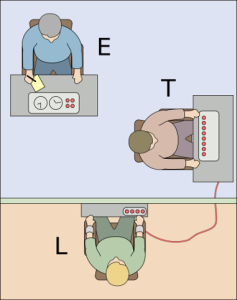

Imagine you’re a participant in what you think is a study about learning and memory. You’re told to teach word pairs to another participant (who’s actually an actor) in the next room, and every time they get an answer wrong, you’re supposed to give them an electric shock. The shocks start mild, but the experimenter tells you to increase the voltage with each mistake. Soon the “learner” is screaming in pain and begging you to stop. But the experimenter, calm and authoritative in his lab coat, tells you to continue.

What would you do? Most people predict they’d stop early in the process. But in Milgram’s (1974) studies, about 65% of participants continued shocking the “learner” all the way to the maximum voltage, even when they believed they might be seriously hurting or even killing another person.

Before you judge these participants too harshly, remember that they were ordinary people who thought they were helping with legitimate scientific research. The experimenter gradually escalated the commitment, took responsibility for the consequences, and used the kind of authority cues (lab coat, official setting, calm demeanor) that usually indicate trustworthiness.

This research helps explain how good people can end up doing terrible things in organizational settings. When authority figures gradually escalate demands, take responsibility for outcomes, and use legitimate-seeming justifications, even ethical people can find themselves crossing lines they never thought they would.

As Milgram (1974) concluded: “The most fundamental lesson of our study is that ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process.”

Social Facilitation and Social Loafing

Here’s a puzzle that stumped psychologists for decades: why do people sometimes perform better in groups and sometimes perform worse? The answer, it turns out, depends on what they’re doing and how good they are at it.

Social facilitation is the tendency to perform better on tasks when others are around. You might notice this when you run faster if someone’s watching, type more accurately when your boss is nearby, or absolutely nail a presentation when you’ve got an audience of your peers. It’s one of the oldest findings in social psychology, and it happens because the presence of others creates a kind of energizing arousal.

Research by Zajonc (1965) shows some pretty fascinating examples: after a light turns green, people drive the first 100 yards 15% faster if another car is next to them. Good pool players improve when people are watching, but bad pool players get even worse when someone is watching.

But here’s the catch: this arousal only helps with tasks you’re already good at. If you’re doing something simple, well-learned, or familiar, having an audience can boost your performance. But if you’re struggling with something complex, new, or challenging, all that extra arousal can actually hurt your performance by overwhelming your thinking capacity.

Think about it this way: if you’re a skilled pianist, you might play beautifully in front of an audience because the arousal energizes your well-rehearsed skills. But if you’re learning a complicated new piece, you’d probably do better practicing alone where you can focus without the extra pressure and arousal.

This has real practical implications for how you approach different tasks. When you’re doing routine work that you’ve mastered, working around others might actually boost your productivity. But when you’re learning something new or tackling a complex problem, you might want to find a quiet space where you won’t be distracted by social cues.

On the flip side, we have social loafing – the tendency for people to put in less effort when working in groups compared to working alone. If you’ve ever been part of a group project where someone didn’t pull their weight, you’ve witnessed social loafing in action.

Researchers first discovered this phenomenon in some surprisingly simple experiments. When people pulled on a rope alone, they used maximum effort. But when they pulled as part of a group, each person’s individual effort decreased as the group got larger. The same thing happened with clapping, shouting, and other tasks – the bigger the group, the less effort each individual contributed (Latané, Williams, & Harkins, 1979).

Why does this happen? Several psychological mechanisms are at play. First, there’s diffusion of responsibility: when you’re part of a group, it’s easy to think, “Someone else will pick up the slack” or “My contribution won’t make that much difference.”

Research by Latané and Dabbs (1975) demonstrated this powerfully: on 1,497 separate occasions in three cities, they had people drop objects in elevators in front of 4,813 bystanders. They found that individuals were less likely to help pick up the objects as the number of people in the elevator increased. Classic diffusion of responsibility in action.

Second, individual accountability often decreases in groups – if your specific contribution can’t be identified or measured, there’s less pressure to perform at your best.

Then there’s the free-riding effect, where some people deliberately reduce their effort while expecting to share equally in the group’s success. This can create a sucker effect where other group members, realizing someone is coasting, also reduce their effort to avoid being taken advantage of. On the positive side, some people engage in social compensation, working extra hard to make up for anticipated poor performance by others.

The good news? Social loafing isn’t inevitable. It’s much less likely to happen when individual contributions are visible and measurable, when the task feels meaningful and important, when groups are smaller rather than larger, and when there’s a culture of accountability and mutual responsibility.

Deindividuation and Group Polarization

Ever notice how people behave differently in crowds than they do individually? Maybe you’ve seen otherwise polite people become aggressive at sporting events, or witnessed how online comment sections can bring out behavior that people would never display face-to-face. This is deindividuation in action.

Deindividuation occurs when people lose their sense of personal identity and self-awareness in group situations. It’s often associated with anonymity, high arousal, and reduced accountability. Think about Halloween parties where people in costumes act way more wildly than usual, or how drivers might behave more aggressively when they’re anonymous behind the wheel. Research by Festinger, Pepitone, and Newcomb (1952) shows that women students delivered twice as much electric shock to a victim when wearing hoods that made them unidentifiable.

What’s important to understand is that deindividuation doesn’t automatically make people antisocial – it just makes them more likely to act on whatever impulses or norms are prominent in the situation. If the group norm is helpful (like helping others), deindividuation can actually increase helpful behavior. But if the group norm is destructive, it can lead to actions that individuals would never consider on their own.

In work settings, deindividuation might occur in large meetings where individual accountability is low, in anonymous feedback systems, or during major organizational changes where normal social structures break down. Being aware of these conditions can help you maintain your individual judgment and ethical standards even in group situations.

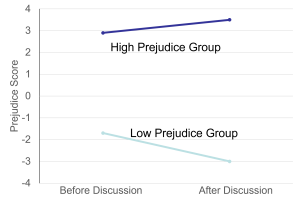

Group polarization reveals another surprising truth about group decision-making: groups don’t necessarily make more moderate decisions than individuals. Instead, they often make more extreme decisions in whatever direction the group was already leaning. This is also called the enhancement of a group’s prevailing attitudes through discussion within the group.

Let’s say you’re part of a team deciding whether to launch a risky new product. If the team members individually lean toward taking the risk, group discussion will probably push them toward taking an even bigger risk than any individual would choose alone. Conversely, if they’re individually cautious, the group will likely become even more conservative.

This happens for several reasons. During group discussion, people hear more arguments supporting the direction they’re already inclined toward, which strengthens their confidence in that position. They also engage in social comparison, trying to show that they’re at least as committed to the group’s preferred direction as everyone else. When responsibility is shared among group members, individuals may also feel more comfortable supporting extreme positions because they won’t bear full accountability for the consequences.

Understanding group polarization is crucial because it shows that group discussion doesn’t automatically lead to better, more balanced decisions. In fact, it can lead to more extreme and potentially riskier choices than any individual would make alone. Research by Moscovici and Zavalloni (1969) shows that if a group is like-minded, discussion strengthens its prevailing opinions – which explains why individual differences among college freshmen at a single university often diminish by the time they become seniors.

Media Attributions

- Virtual Meeting © Dean Calma is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Autokinetic Phenomenon adapted by Jay Brown

- Asch Conformity adapted by Jay Brown

- Milgram Obedience © Fred the Oyster is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Norms, Conformity, & Obedience

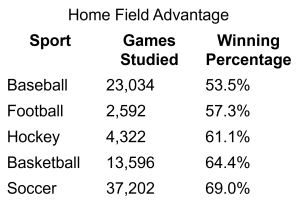

- Home Field Advantage

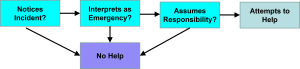

- Bystender Intervention adapted by Jay Brown

- Group Polarization adapted by Jay Brown