13-2: Group Performance

Group Development and Structure

Group Development and Structure

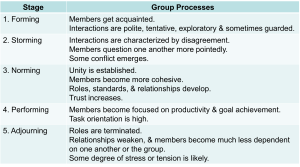

Groups don’t just magically start functioning effectively from day one. Like relationships, they go through predictable stages of development, each with its own challenges and opportunities. Bruce Tuckman identified five stages that most groups experience, and understanding these can help you navigate team dynamics way more effectively.

Forming is the “getting to know you” stage. Everyone’s being polite and tentative, trying to figure out what’s expected and where they fit in. Productivity is usually pretty low during this stage because people are more focused on understanding the situation than on getting work done. You’ve probably experienced this during the first meeting of a new team or committee – lots of introductions, general discussion, and not much concrete progress.

Storming is where things get interesting – and sometimes pretty uncomfortable. This is when conflicts emerge as people start asserting their preferences and challenging initial assumptions. Who’s going to lead? What procedures should we follow? What are our real priorities? While storming can feel unpleasant, it’s actually a necessary part of group development. Groups that skip this stage often end up with underlying tensions that hurt their effectiveness later.

Norming is when the group starts to gel. Members develop shared expectations, establish working relationships, and create the communication patterns and decision-making procedures they’ll use going forward. This is when you start to see real teamwork emerging – people know their roles, understand how to work together, and have established the trust and coordination necessary for effective collaboration.

Performing is the sweet spot where everything clicks. The group has worked out its process issues and can focus its energy on actually accomplishing its goals. Communication flows smoothly, conflicts are handled constructively, and productivity is high. Not all groups reach this stage, but those that do often achieve results that exceed what the individuals could accomplish separately.

Adjourning happens when temporary groups complete their tasks or when ongoing groups experience major membership changes. This stage involves wrapping up relationships, transferring knowledge, and dealing with the emotional aspects of group dissolution. It’s often overlooked, but handling this stage well can preserve positive relationships and valuable learning for future group experiences.

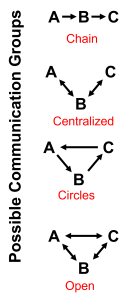

The structure that groups develop during these stages significantly impacts their effectiveness. Communication structure determines how information flows within the group. Research shows that the best structure depends on the task at hand. Centralized structures, where information flows through one key person, can be efficient for simple tasks but may create bottlenecks for complex work. Decentralized structures allow more flexible information sharing but can be harder to coordinate.

Role structure defines who does what within the group. Clear roles enhance performance by reducing confusion and ensuring all necessary functions are covered. Groups need members to assume different roles: task-oriented roles (offering new ideas, coordinating activities, finding new information) and social-oriented roles (encouraging cohesiveness and participation). Research by Stewart, Fulmer, and Barrick (2005) shows that people high in conscientiousness tend to fill task-oriented roles, while people high in agreeableness tend to fill social-oriented roles. But roles that are too rigid can prevent groups from adapting when circumstances change.

Status structure reflects the relative influence and prestige of different group members. Some status differences can help with coordination by clarifying who has decision-making authority, but extreme status differences may shut down communication and participation from lower-status members.

Group Cohesiveness and Performance

Group cohesiveness is essentially how much group members like each other and want to stay together. It’s that “we’re all in this together” feeling that makes some teams feel like families while others feel like collections of strangers who just happen to be working on the same thing. Cohesion is the strength of group members’ attraction to maintaining membership in the group and the strength of links developed among group members.

Cohesive groups generally perform way better than non-cohesive ones. Research by Beale, Cohen, Burke, and McLendon (2003) shows that high cohesion has been linked to higher productivity and efficiency, better decision quality, greater member satisfaction, more member interaction, and increased employee courtesy. Members communicate more openly, cooperate more readily, and show higher satisfaction with their group experience. They’re also more likely to engage in organizational citizenship behaviors – going above and beyond their formal roles to help the group succeed (Kidwell, Mossholder, & Bennett, 1997).

But cohesiveness isn’t automatically good. Sometimes it can lead to problems like groupthink, where the desire to maintain harmony becomes more important than making good decisions. The key is having the right amount of cohesiveness for the situation – enough to promote cooperation and commitment, but not so much that it stifles critical thinking.

Several factors influence how cohesive a group becomes. Stability of membership is important because relationships take time to develop. Groups in which members remain for long periods are more cohesive and perform better than groups with high turnover. Research by Harrison, Mohammed, McGrath, Florey, and Vanderstoep (2003) shows that groups whose members have previously worked together also perform better than groups whose members are unfamiliar with one another.

Group size matters too. Smaller groups typically develop stronger bonds than larger ones because it’s easier to form relationships with fewer people. Research by Shaw and Shaw (1962) consistently shows that large groups have lower productivity, less coordination, lower morale, are less active, less cohesive, and more critical. Studies by Frank and Anderson (1971) suggest that groups perform best and have greatest member satisfaction when they consist of approximately five members.

At Amazon, they follow what they call the “two-pizza rule” – teams should never be so large that it takes more than two pizzas to feed them! As they put it, “A smaller team is more likely to stay focused, have a clearer idea of what they’re supposed to do each day, and waste less time in meetings by virtue of always being in contact with each other.”

Isolation can increase cohesiveness. Groups that are isolated or located away from other groups tend to be highly cohesive, partly because members depend more on each other for social interaction.

External factors also play a role. Outside pressure can actually increase cohesiveness by giving the group something to unite against – think about how shared challenges often bring teams closer together. This response can be explained by psychological reactance: when we believe someone is trying to influence us, we often react by doing the opposite. You see this a lot during labor negotiations between company management and unions.

Group status influences cohesiveness because people are more motivated to maintain membership in high-status groups. The higher the group’s status, the greater its cohesiveness. Importantly, the group doesn’t actually have to have high status – it’s important that members believe they have high status. The Marine Corps builds this through tough basic training that creates the belief that Marines are among “just a few good men.”

The question of homogeneity versus heterogeneity is particularly interesting. Groups composed of similar people often develop stronger interpersonal bonds and experience less conflict. But diverse groups may achieve better performance because they bring different perspectives and capabilities to the task.

The research suggests that optimal group composition might include mostly similar members with one or two different individuals who can provide alternative viewpoints without creating too much conflict. Research by Mullen, Johnson, and Drake (1987) shows that slightly-heterogeneous groups (such as four men and one woman) performed somewhat better than both completely homogeneous and completely heterogeneous groups. This slight diversity can stimulate creativity and prevent tunnel vision while maintaining enough similarity for effective collaboration.

Team Effectiveness and Performance

So what makes some teams spectacularly successful while others struggle to accomplish even basic tasks? Team effectiveness is complex, but researchers have identified several key factors that consistently predict success.

Team effectiveness encompasses three main dimensions. Team Performance includes traditional metrics like productivity, quality, and cost control that directly reflect the team’s contribution to organizational objectives. Attitudes encompass team member reactions including job satisfaction, trust in management, and organizational commitment that influence long-term sustainability. Withdrawal behaviors include turnover, absence, and tardiness that reflect team member satisfaction and commitment.

There’s a growing realization that the complexity of work in the 21st century requires collaboration. Many different skills and so much knowledge are required that individuals can no longer accomplish certain tasks on their own.

Teams need to excel at both taskwork and teamwork to be truly effective. Taskwork includes all the technical activities directly related to accomplishing objectives – goal setting, planning, problem-solving, performance monitoring. Teamwork involves the interpersonal and coordination activities that enable effective collaboration – communication, coordination, feedback, maintaining team cohesion.

Teamwork revolves around communication and coordination among team members, feedback, and team cohesion/norms. Neither taskwork nor teamwork alone is sufficient – you need teams that can both do the work and work together effectively.

Several factors predict team effectiveness:

Organizational Context provides the environmental conditions that support or constrain team performance – resources, rewards, information systems, cultural support for teamwork.

Group Composition and Size significantly impact effectiveness. Research consistently shows that teams of about five members optimize the balance between diverse perspectives and manageable coordination.

Group Work Design encompasses task characteristics, role definitions, and structural arrangements that influence how teams organize their work.

Intragroup Processes include communication patterns, decision-making procedures, conflict management, and norm development.

External Group Processes involve relationships with other organizational units, customers, and stakeholders.

Personality plays a bigger role in team effectiveness than many people realize. Research by Bell (2007) shows that teams with high variability on extraversion and low variability on conscientiousness are most effective, balancing diverse social styles with consistent work orientation. Backup behavior – when team members help others who need assistance – significantly impacts team success. When an individual perceives a team member needs help, the personalities of both the helper and recipient influence effectiveness.

General mental ability consistently predicts performance across various types of teams and tasks (Devine & Phillips, 2001). Group preference appears to be a stable disposition that can be measured – some people naturally prefer collaborative work while others perform better individually.

Research shows that even one team member who lacks critical personality traits can increase stress and decrease performance for the entire team, emphasizing the importance of careful selection.

Several factors should guide team member selection. Consider both individual capabilities and group-level factors including size, diversity, and personality mix. Select based on both technical qualifications and teamwork capabilities. Use instruments designed to identify individuals likely to succeed in team environments like the Teamwork Test (situational judgment test identifying KSAOs that predict teamwork better than taskwork), Team Role Test (taps knowledge about team roles and when certain roles are most important), and Team Role Experience and Orientation (TREO) (improved version building on previous assessments).

Research by Gully, Incalcaterra, Joshi, and Beaubien (2002) shows that groups consisting of high-ability members outperform those with low-ability members. Groups whose members believe their team can be successful both at specific tasks (high team efficacy) and at tasks in general (high team potency) perform better than less confident groups.

Groups whose members score high in openness to experience and emotional stability perform better overall. For intellectual tasks, bright group members improve performance. For physical tasks (like sports teams), members who score high in conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness enhance group performance.

Teamwork Pays, Even for Chickens

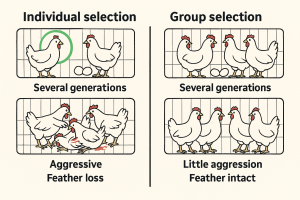

Here’s something that’ll absolutely blow your mind: research by Wilson (2007) found personality-related group performance effects even in chickens, providing a fascinating biological perspective on group dynamics that parallels human organizational behavior!

The study invol ved two different breeding approaches over multiple generations. In the individual selection approach, researchers identified the single highest egg-laying hen from each cage and bred only these “superstar” individuals. You might think this would create a strain of super-productive chickens, right? Wrong! What happened was shocking: after several generations, when these genetically “superior” hens were placed together in groups, they became incredibly aggressive. They pecked each other viciously, pulled out each other’s feathers, and actually killed six members of their group. The descendants of these individual high performers had achieved their superior egg production not through better genetics, but by suppressing the productivity of their cage-mates through aggressive behavior.

ved two different breeding approaches over multiple generations. In the individual selection approach, researchers identified the single highest egg-laying hen from each cage and bred only these “superstar” individuals. You might think this would create a strain of super-productive chickens, right? Wrong! What happened was shocking: after several generations, when these genetically “superior” hens were placed together in groups, they became incredibly aggressive. They pecked each other viciously, pulled out each other’s feathers, and actually killed six members of their group. The descendants of these individual high performers had achieved their superior egg production not through better genetics, but by suppressing the productivity of their cage-mates through aggressive behavior.

In contrast, the group selection approach bred entire cages of chickens based on the total egg production of the whole group, regardless of which individual hens were the highest producers. The results were dramatically different: after several generations, these group-selected chickens were not only highly productive individually, but they also worked together harmoniously when placed in new groups. They showed little aggression, maintained their feathers, and sustained high group productivity without harming their cage-mates.

This chicken study brilliantly illustrates a crucial principle about team effectiveness: the traits that make someone a high individual performer can be completely different from (or even opposite to) the traits that make someone an effective team member. The “superstar” chickens were essentially workplace bullies who achieved high personal performance by undermining others around them. Meanwhile, the group-selected chickens had evolved traits that supported both individual and collective success.

The implications for human organizations are profound. This research suggests there may be genetic and personality factors that predispose some individuals toward collaborative success while others may be naturally inclined toward competitive behaviors that undermine team effectiveness. It also demonstrates why organizations need to be careful about selecting and promoting based purely on individual performance metrics without considering how those individuals affect the performance of their teammates.

This biological evidence supports what we see in human teams: sometimes the person who looks like the highest performer individually is actually toxic to overall team productivity, while the most effective team members might be those who lift everyone’s performance rather than standing out individually.

Media Attributions

- Group © Geralt is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tuckman’s Five Stages of Group Development

- Communication Structure adapted by Jay Brown

- Absolutely No Swimming with Alligators © Jay Brown and Copilot

- Chicken © Raquel Candia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Chicken Study © Jay Brown and Copilot