13-3: Types of Work Teams

In today’s workplace, you’re going to find yourself working on teams whether you like it or not. Whether you’re brainstorming with colleagues, serving on committees, or collaborating on projects, your success is going to depend partly on how well you understand what happens when people come together. This shift toward team-based work isn’t just some trendy management fad – it’s happening because modern challenges are too complex for any one person to handle alone.

In today’s workplace, you’re going to find yourself working on teams whether you like it or not. Whether you’re brainstorming with colleagues, serving on committees, or collaborating on projects, your success is going to depend partly on how well you understand what happens when people come together. This shift toward team-based work isn’t just some trendy management fad – it’s happening because modern challenges are too complex for any one person to handle alone.

Think about developing a new app. You need programmers, designers, marketers, user experience experts, and project managers all working together. No single person has all these skills, so success depends on how well the group can coordinate their diverse talents. But here’s the catch – putting smart people together doesn’t automatically create a smart team. Sometimes it creates a complete mess.

The good news? Once you understand how groups work – both their superpowers and their kryptonite – you can help make any team more effective while protecting yourself from the not-so-great aspects of group influence.

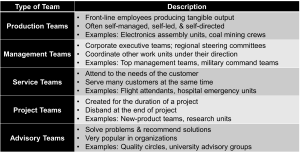

Production Teams

Production teams consist of frontline employees who produce tangible outputs – think assembly line workers, construction crews, or restaurant kitchen staff. These teams typically focus on efficiency, quality, and safety while working with established procedures and technologies. Success often depends on clear role definitions, standardized processes, and effective coordination among members who perform interdependent tasks. Many production teams have morning meetings to ensure communication and interdependent work toward production goals.

The key to production team effectiveness lies in understanding that these teams operate within highly structured environments where consistency and coordination are paramount. Unlike creative or strategic teams that might benefit from ambiguity and exploration, production teams thrive when everyone knows exactly what they’re supposed to do and how their work fits with others’.

Autonomous work groups represent a special type of production team with expanded authority over planning, work allocation, and personnel decisions. These self-managing teams have control over various functions including planning shift operations, allocating work, determining work priorities, performing diverse work tasks, and recommending new hires. Research by Cordery (1996) shows they often achieve higher member satisfaction and superior performance compared to traditionally supervised groups. However, they require members with diverse skills and strong interpersonal capabilities to function effectively without external supervision.

The transition to autonomous work groups can be challenging because it requires both management and employees to fundamentally rethink traditional power structures. Success depends on extensive training, clear boundaries about decision-making authority, and strong support systems for when problems arise.

Project Teams

Project teams are temporary groups created to solve specific problems or complete particular projects. Think about a team assembled to develop a new marketing campaign, implement a software system, or plan a major event. These teams bring together people with diverse expertise relevant to the project requirements, then disband when objectives are achieved.

Some people prefer permanent team assignments because project teams can create uncertainty about future work and career advancement opportunities. Organizations need to address these concerns through career development programs and fair assignment procedures.

Matrix organizations increasingly use arrangements where individuals work simultaneously on multiple project teams while reporting to both project managers and functional managers. This maximizes utilization of human resources while providing diverse development experiences, but it can also create role conflict and competing priorities.

The challenge with matrix structures is managing the complexity of multiple reporting relationships and competing demands on team members’ time and attention. Success requires sophisticated project management systems and clear communication about priorities when conflicts arise.

Quality Circles and Continuous Improvement Teams

Quality circles involve small groups (typically 6 to 12 employees) who meet regularly to identify work-related problems and generate ideas to increase productivity or product quality. Originating from Japanese management practices, quality circles focus on continuous improvement through employee involvement and expertise.

The effectiveness of quality circles depends heavily on management support and responsiveness. Since circle members typically lack formal authority to implement their recommendations, management must seriously consider and act on feasible suggestions to maintain member motivation.

Research shows that quality circles work best when they focus on problems within the team’s direct experience and control, receive adequate training in problem-solving techniques, and operate within a culture that genuinely values employee input. When these conditions aren’t met, quality circles can become exercises in frustration rather than genuine improvement efforts.

Virtual Teams

Virtual teams consist of members working in different locations who communicate primarily through electronic media. The rise of remote work and global organizations has made virtual teams increasingly common, offering advantages like access to geographically dispersed talent and reduced travel costs.

However, virtual teams face unique challenges. Research suggests that teams become less effective when approximately 90% of communication is computer-mediated, indicating that some face-to-face interaction enhances team performance. Even small amounts of in-person time can significantly improve virtual team effectiveness.

Requirements for categorizing a team as virtual include use of computer-mediated communication and geographically dispersed members. There are gradations of virtuality, with the “tipping point” occurring when about 90% of communication becomes computer-mediated.

Virtual teams must work harder to establish trust, coordinate activities, and maintain team cohesion. Successful virtual teams typically establish clear communication protocols, use multiple communication channels, and create structured opportunities for relationship building. They also need leaders who are skilled at managing across distances and technologies.

The key insight about virtual teams is that technology alone doesn’t solve the fundamental challenges of teamwork – it just changes how those challenges manifest. Virtual teams still need clear goals, defined roles, effective communication, and mutual accountability. They just need to achieve these things through different means.

Multiteam Systems

Multiteam systems involve multiple teams working toward collective goals that require interdependent activity among component teams. These complex arrangements are increasingly common in industries requiring coordination among specialized teams with different expertise. Managing these systems requires sophisticated understanding of inter-team dynamics and coordination mechanisms. They may include hierarchically-oriented individual subgoals with superordinate goals requiring interdependent activity.

Think about a hospital where surgical teams, nursing teams, pharmacy teams, and administrative teams all need to coordinate their activities to provide patient care. Each team has its own specialized expertise and internal dynamics, but success depends on how well they work together as a larger system.

Multiteam systems present unique challenges because they must manage both intra-team dynamics (what happens within each team) and inter-team dynamics (what happens between teams). This requires coordination mechanisms that can handle complexity without creating bureaucratic delays.

Future Directions and Practical Applications

The world of teamwork continues evolving rapidly. Virtual team proliferation will continue as organizations seek global talent while reducing costs, but virtual teams require different management approaches including attention to communication technology, relationship building, and cultural differences.

Fluid team membership is becoming more common, with people participating in multiple teams simultaneously or moving frequently between assignments. This flexibility optimizes resource utilization but requires new approaches to team development and performance management.

Artificial intelligence and automation will increasingly influence team composition and functioning by changing task requirements and enabling new forms of human-machine collaboration. Teams may include AI systems as members, requiring new approaches to team design and management.

Here are evidence-based recommendations for improving team effectiveness:

For Group Composition, consider both individual capabilities and group-level factors including size, diversity, and personality mix. Select team members based on both technical qualifications and teamwork capabilities. Aim for teams of approximately five members for optimal balance. Include mostly similar members with one or two different individuals for alternative perspectives.

For Process Design, address communication structures, decision-making procedures, and conflict management approaches appropriate for specific tasks and contexts. Develop standard operating procedures while maintaining flexibility for adaptation. Build in regular check-ins and feedback mechanisms.

For Leadership Development, build group facilitation skills and conflict management capabilities. Develop deep understanding of group dynamics and development stages. Learn to guide groups through development stages while maintaining focus on both task and relationship considerations. Avoid early advocacy for particular solutions and encourage open discussion.

For Training Programs, address both technical skills and teamwork capabilities including communication, collaboration, and conflict resolution. Provide team-based training, which is often more effective than individual training for developing coordination skills. Include training on groupthink recognition and prevention.

For Performance Management, include both individual and team-level metrics. Provide feedback that supports both task accomplishment and team development. Use balanced scorecards to help teams monitor multiple aspects of effectiveness.

For Technology Support, enhance rather than replace human interaction. Provide tools for coordination, communication, and performance monitoring. Evaluate technology adoption carefully to ensure it supports rather than undermines team effectiveness.

For Organizational Culture, value teamwork while maintaining individual accountability and recognition. Support appropriate risk-taking, learning from mistakes, and constructive conflict. Create cultures that can significantly enhance team effectiveness.

Media Attributions

- Team © Mohamed Hassan is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Types of Work Teams