13-4: Group Decision-Making

One of the most important things groups do is make decisions, and this is where group dynamics get really complex. Groups have some inherent advantages over individual decision-makers – they can pool more information, catch each other’s errors, and generate more creative solutions. But they also face unique challenges that can actually make their decisions worse than what individuals would choose.

Here’s a quick example that’ll blow your mind: A man bought a horse for $60 and sold it again for $70. Then he bought it back for $80 and sold it again for $90. How much money did he make in the horse business?

Here’s a quick example that’ll blow your mind: A man bought a horse for $60 and sold it again for $70. Then he bought it back for $80 and sold it again for $90. How much money did he make in the horse business?

Only 45% of college students answer this correctly when working alone. But students who worked in groups with an inactive leader answered correctly 72% of the time, and those with active leaders answered correctly 84% of the time. (The answer, by the way, is $20 – he made $10 on each transaction.)

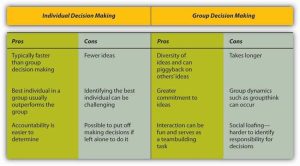

Advantages and Disadvantages of Group Decision-Making

Let’s start with the advantages. When you bring together people with different knowledge, experience, and perspectives, you theoretically have access to much more information than any individual possesses. Group members can also serve as error-checkers, identifying flaws or oversights that might slip past a single decision-maker. And when people participate in making a decision, they’re usually more committed to implementing it effectively.

But groups also face several potential disadvantages. Decision-making takes longer when you have to coordinate multiple schedules, share information, and build consensus. Social pressures within groups can lead people to suppress dissenting opinions or go along with ideas they privately think are flawed. And sometimes the most vocal or high-status group members dominate the discussion, preventing the group from accessing all available information and perspectives.

The Group Decision-Making Process

Effective group decision-making typically follows several stages:

Problem Diagnosis involves getting everyone on the same page about what the problem actually is, what the group’s goals are, and what obstacles need to be overcome. This sounds simple, but it’s where many groups go wrong. Common problems include confusing facts with opinions and confusing symptoms with underlying causes.

Solution Generation focuses on understanding the problem well enough to identify potential solutions. The key here is to suspend judgment temporarily and encourage creative thinking. Brainstorming can be useful during this stage, though research shows that individual brainstorming followed by group integration often works better than traditional group brainstorming sessions. Common problems include suggesting irrelevant solutions and looking at what should have been done rather than looking forward.

Solution Evaluation involves systematically considering the pros and cons of each potential solution. Common problems include failing to consider the potential downsides to each solution, attacking the person who proposed a solution rather than focusing on the solution itself, and allowing less assertive group members’ ideas to be ignored.

Solution Selection requires reaching agreement on the best available option. This is where group dynamics can really complicate things – powerful members might push their preferences, people might choose politically correct rather than optimal solutions, or the group might fail to consider implementation challenges.

Finally, Implementation Planning determines how to actually carry out the decision and monitor progress. Groups sometimes exclude key people from this stage or fail to address the tendency for groups to make more extreme decisions than individuals would choose (the risky-shift phenomenon).

Information Sharing Challenges

One of the biggest challenges in group decision-making is information sharing. You might think that putting knowledgeable people together would automatically pool all their information, but research shows this often doesn’t happen. Groups tend to spend most of their time discussing shared information (information that every group member holds) while giving insufficient attention to unshared information (information that only individual members possess).

This bias toward shared information occurs partly because shared information seems more credible when multiple people can confirm it, and partly because discussing familiar information is more comfortable than introducing novel ideas. The result is that groups often fail to realize their theoretical advantages in information processing.

Brainstorming Effectiveness

Brainstorming deserves special mention because it’s so widely used despite research showing that traditional group brainstorming often underperforms individual brainstorming. The problems include production blocking (people having to wait their turn to speak), evaluation apprehension (fear of looking foolish), and social loafing (reduced individual effort in group settings).

Research by Valacich, Dennis, and Nunamaker (1992) shows that electronic brainstorming can address some of these issues by allowing anonymous, simultaneous input. Computer-mediated brainstorming sessions often generate more ideas and higher-quality solutions than traditional face-to-face sessions.

The key insight about brainstorming is that the goal should be quantity first, quality second. When people worry too much about whether their ideas are good, they stop generating ideas altogether. The evaluation phase should be completely separate from the generation phase.

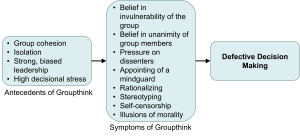

Groupthink

Now we come to one of the most dangerous phenomena in group decision-making: groupthink. This occurs when the desire for harmony and consensus becomes so strong that it overrides realistic evaluation of alternatives. The result is often disastrously flawed decisions made by groups of intelligent, well-intentioned people.

Irving Janis (1982) first identified groupthink while analyzing major foreign policy failures like the Bay of Pigs invasion and the decision to escalate the Vietnam War. He found consistent patterns of flawed thinking that led to these disasters, despite the involvement of some of the brightest minds in government. Other examples include Pearl Harbor, the Challenger disaster, and Watergate.

Groupthink is most likely to occur when groups are highly cohesive, insulated from outside opinions, led by directive leaders who push particular solutions, and operating under stress without systematic decision-making procedures. Sound familiar? These conditions exist in many organizational settings, which is why understanding groupthink is so important for anyone working in teams.

Symptoms of Groupthink

The symptoms of groupthink are like warning signs that a group’s decision-making process has gone completely off the rails:

Illusion of invulnerability creates excessive optimism and encourages extreme risk-taking. The group starts believing it can’t fail or make serious errors, leading to inadequate consideration of risks and alternative approaches.

Collective rationalization involves explaining away warnings or negative feedback that might cause the group to reconsider its assumptions. Instead of incorporating contradictory evidence into their decision-making, groups experiencing groupthink tend to dismiss it or find reasons why it doesn’t apply to their situation.

Unquestioned belief in group morality leads members to ignore ethical considerations because they assume their group’s inherent goodness justifies whatever actions they take. This can result in serious ethical violations when groups pursue goals they consider important.

Stereotyped views of outgroups cause groups to underestimate opponents or external stakeholders, leading to strategic miscalculations. Complex external actors get reduced to simple stereotypes, preventing realistic assessment of how they might respond to the group’s decisions.

Direct pressure on dissenters emerges when group members discourage anyone who questions the group consensus. This pressure can range from subtle disapproval to explicit sanctions, but the message is clear: don’t rock the boat.

Self-censorship happens when individual members suppress their own doubts and concerns to avoid disrupting group harmony. People may have important information or insights but choose not to share them if they conflict with the emerging consensus.

Illusions of unanimity develop when self-censorship and pressure on dissenters create the appearance of unanimous agreement. The group mistakes silence for consent and assumes that lack of expressed disagreement indicates genuine consensus.

Self-appointed mindguards are group members who protect the group from information that might disturb its confidence. They may screen external information or discourage outsiders from sharing contrary perspectives with the group.

Preventing Groupthink

Preventing groupthink requires intentional effort and structural changes to group processes. Groups should explicitly discuss groupthink symptoms to develop awareness and recognition skills. Assign devil’s advocate roles to ensure that alternative viewpoints receive serious consideration. Invite outside experts to meetings to provide fresh perspectives and challenge group assumptions. Encourage a culture where differences are valued. Debate the ethics of potential solutions.

Perhaps most importantly, leaders need to avoid early advocacy for particular solutions and should explicitly encourage open discussion of alternatives. They should demonstrate willingness to change their minds when presented with compelling evidence and should reward critical thinking even when it challenges preferred positions.

Research by Mullen, Anthony, Salas, and Driskell (1994) shows that groups can effectively prevent groupthink by building structured devil’s advocacy into their decision-making processes and by ensuring that all members feel safe expressing dissenting opinions.

Media Attributions

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Levels of Decision Making © Saylor Academy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Horse © Евгения is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Challenger Crew © NASA is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Groupthink adapted by Jay Brown