14-2: Traditional Theories of Leadership

Leadership research has a fascinating history that reflects changing ideas about what makes leaders effective. Early approaches were influenced by historical perspectives that were split between “Great Man” theories and zeitgeist approaches.

Leadership research has a fascinating history that reflects changing ideas about what makes leaders effective. Early approaches were influenced by historical perspectives that were split between “Great Man” theories and zeitgeist approaches.

Historical Perspectives: Great Man vs. Zeitgeist

Great Man theories suggested that outstanding individuals create historical change through their unique, almost superhuman capabilities. This view believes that history is the product of a few really spectacular people. Think about how we often talk about figures like Steve Jobs, Winston Churchill, or Martin Luther King Jr. – as if their individual genius was the primary driver of major changes.

Zeitgeist approaches took the opposite view, arguing that historical forces create conditions where leadership emerges inevitably. This approach says history is inevitable – any historical event is a culmination of all the events that come before it. From this perspective, if Steve Jobs hadn’t revolutionized personal computing, someone else would have because the technological and market conditions were ripe for that kind of innovation. George Washington was nothing special; the situation in the American Colonies was just ripe for revolution, and someone had to be in charge.

The Apple example perfectly illustrates this tension. Great Man theorists might attribute Apple’s success entirely to Steve Jobs’ genius and vision. Zeitgeist theorists might argue that technological and market conditions created opportunities that various individuals could have exploited successfully.

Most contemporary researchers recognize that leadership effectiveness results from interactions between individual attributes and situational circumstances – it’s both the person and the situation.

Sources of Leader Greatness

Two common sources of what we might call leader greatness are:

- Galvanizing experiences: Transformative personal experiences – like overcoming serious illness, surviving adversity, or witnessing injustice – may develop resilience and perspective that enhance leadership capabilities.

- Admirable traits: Exceptional traits like intelligence, persistence, or optimism may enable individuals to achieve results beyond normal expectations.

Here’s where it gets interesting – the same traits can be interpreted very differently depending on the situation. Consider Rudolph Giuliani’s leadership during 9/11. Before September 11, 2001, his directive style was often criticized as heavy-handed or dictatorial. But following the terrorist attacks, those same behavioral tendencies were interpreted as resilience, courage, and effective crisis leadership. The context completely changed how people viewed his leadership approach.

Trait Theories of Leadership (1930s-1940s)

Trait theories of leadership dominated research during the 1930s and 1940s, when researchers tried to identify individual characteristics that distinguished effective leaders from everyone else. They focused on traits like:

But then came Stogdill’s 1948 review – a watershed moment that changed everything. After analyzing decades of trait research, Stogdill (1948) concluded that no universal traits consistently predicted leadership across different situations. This influential finding demonstrated that leadership effectiveness depended on interactions between leader characteristics and situational factors rather than simple trait possession.

Problems with trait theories included:

- Major disagreements about how to define and measure traits

- Different researchers studying similar concepts using completely incompatible methods

- Viewing leaders as existing in a bubble rather than in a larger context

- Obsession with productivity as the primary effectiveness criterion

- Overlooking important factors like follower satisfaction and commitment

However, trait research experienced a reemergence as measurement and statistical techniques improved. The “good person” theory suggested that intelligence, dominance, and masculine orientation predict who emerges as a leader and how they’re perceived, though not necessarily how effective they actually are.

Big Five personality factors have shown particularly interesting relationships with leadership. Extraversion and conscientiousness demonstrate strong relationships with leadership outcomes, with research suggesting that personality factors account for about 50% of variance in who emerges as a leader.

Here’s the catch: traits seem to predict who will be perceived as a leader and emerge in leadership roles better than they predict actual leadership effectiveness once someone is in a leadership position. This suggests that different factors may influence leader selection versus leader performance.

Power Approaches to Leadership

Power approaches to leadership recognize that leadership fundamentally involves influence relationships where leaders possess resources that enable them to affect follower attitudes and behaviors. Understanding power dynamics provides insights into how leadership actually works while highlighting potential problems when power is misused.

Power is a resource that provides the potential to influence the attitudes and behaviors of others. Managers have power that subordinates do not have – an organization gives a manager the power to make decisions about people, expenses, methods of production, and so forth. The higher the manager is in the organization, the more power, or authority, they tend to have.

French and Raven’s power model (French & Raven, 1959) identifies five distinct power sources that leaders can use to influence followers:

- Legitimate Power

- Stems from organizational authority formally given to leaders through their position or role

- Authority-based power that works through follower recognition that leaders have the right to make certain decisions

How to increase and maintain:

- Gain more formal authority

- Use symbols of authority

- Get people to acknowledge authority

- Exercise authority regularly

- Follow proper channels

- Back up authority with other power sources

How to use effectively:

- Make polite, clear requests

- Explain reasons for requests

- Don’t exceed scope of authority

- Be sensitive to concerns

- Follow up to verify compliance

- Reward Power

- Involves control over positive outcomes that followers value – compensation, recognition, promotions, interesting assignments

- Leaders can influence behavior by providing incentives for desired performance

How to increase and maintain:

- Discover what people need and want

- Gain control over valued rewards

- Ensure people know you control rewards

- Don’t promise more than you can deliver

- Avoid manipulative use

- Keep incentives simple

How to use effectively:

- Offer desirable, fair, and ethical rewards

- Explain criteria for giving rewards

- Provide rewards as promised

- Use rewards symbolically to reinforce behavior

- Expert Power

- Comes from special knowledge, skills, or expertise that others need or value

- Technical experts and experienced professionals can influence others through their specialized knowledge

How to increase and maintain:

- Gain relevant knowledge

- Stay informed about technical matters

- Develop exclusive information sources

- Use symbols to verify expertise

- Demonstrate competence by solving problems

- Don’t make rash statements

How to use effectively:

- Explain reasons for requests

- Provide evidence that proposals will succeed

- Listen to concerns

- Show respect (don’t be arrogant)

- Act confident in crisis

- Referent Power

- Emerges from respect, admiration, and identification that followers feel toward leaders

- Relationship-based power operating through followers’ desires to please or emulate leaders

How to increase and maintain:

- Show acceptance and positive regard

- Act supportive and helpful

- Don’t manipulate for personal advantage

- Defend others’ interests

- Keep promises

- Make self-sacrifices to show concern

How to use effectively:

- Use personal appeals when necessary

- Indicate requests are important to you

- Don’t ask for excessive favors

- Provide examples of proper behavior

- Coercive Power

- Involves control over punishments or negative consequences that followers want to avoid

- While it can produce compliance, it often creates resentment and resistance

How to increase and maintain:

- Identify credible penalties for unacceptable behavior

- Gain authority to use punishments

- Don’t make rash threats

- Use only legitimate punishments

- Fit punishments to infractions

How to use effectively:

- Inform people of rules and penalties

- Give ample warnings

- Understand situations before punishing

- Remain calm and helpful

- Administer discipline privately

Understanding power corruption is crucial because substantial influence over others can corrupt decision-making processes and create unrealistic perceptions of personal capabilities and entitlements. As the saying goes, “absolute power corrupts absolutely!” Leaders must maintain awareness of corruption risks while establishing systems that prevent power abuse.

Behavioral Theories of Leadership (1950s-1960s)

Behavioral theories of leadership emerged when trait approaches proved insufficient for predicting leadership effectiveness. Researchers reasoned that if traits couldn’t explain leadership success, perhaps leader behaviors would provide better understanding and more practical guidance for leadership development. This approach implied that leaders could be trained.

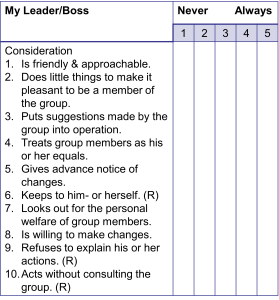

The Ohio State studies (Fleishman, 1967) identified two major dimensions of leader behavior that became foundational for subsequent leadership research:

Initiating Structure (Task-Oriented)

- Encompasses task-oriented behaviors including role definition, goal setting, planning, and performance monitoring

- Leaders high on initiating structure provide clear direction and establish systems for task accomplishment

- Includes assigning specific tasks, planning ahead, and letting group members know what’s expected

Consideration (Relationship-Oriented)

- Involves relationship-oriented behaviors that demonstrate concern and respect for followers

- Includes participative decision-making, rapport building, and supportive interactions

- Considerate leaders attend to follower needs and maintain positive interpersonal relationships

An important finding was the independence of behavioral dimensions – initiating structure and consideration represent separate dimensions rather than opposite ends of a single continuum. Leaders can be high or low on both dimensions, creating four possible behavioral combinations.

Research results regarding optimal behavioral combinations have been mixed, with effectiveness depending on situational factors rather than universal behavioral prescriptions. Sometimes high levels of both work best, but other times the situation determines what behavioral emphasis is most effective.

There may even be curvilinear relationships between behavioral dimensions and effectiveness, where moderate levels sometimes produce better results than extreme high or low levels. Too much initiating structure might create rigidity and reduce follower autonomy, while too little structure might lead to confusion and poor coordination.

Contingency Theories of Leadership

By now you might be thinking, “This is getting complicated – isn’t there just one best way to lead?” The answer, unfortunately for those who like simple solutions, is no. Contingency approaches to leadership recognize that effectiveness depends on matches between leader characteristics, follower needs, and situational demands rather than universal leadership prescriptions.

Leadership is more flexible – different leadership styles should be used at different times depending on the circumstances. There is no single best type of leader or set of leader behaviors. Contingency theories take into account situational and contextual variables. Good leadership may depend on:

- Type of staff

- History of the business

- Culture of the business

- Quality of relationships

- Nature of changes needed

- Accepted norms within the institution

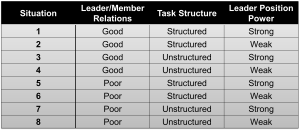

Fiedler’s Contingency Theory

Fiedler’s Contingency Theory (Fiedler, 1967) represents one of the most influential contingency approaches. Fiedler proposed that leadership effectiveness results from interactions between leader orientation and situational favorability. He argued that leader orientation represents a stable personality characteristic that can’t be easily changed, making situation-leader matching critical for effectiveness.

Leader Orientation: The Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) Scale

Fiedler developed the Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) Scale to measure leader orientation by asking leaders to describe their least preferred coworker using bipolar adjectives. His assumption was that everyone’s least preferred coworker is equally unpleasant on average, but relationship-motivated leaders describe these individuals more positively than task-motivated leaders.

- Task-oriented leaders (low LPC scores) focus primarily on task accomplishment and view interpersonal relationships as secondary to goal achievement

- Relationship-oriented leaders (high LPC scores) emphasize interpersonal relationships and view positive social interactions as important components of leadership effectiveness

Since the LPC is considered a “personality” measure, leader orientation is stable and inherent in the leader – you can’t change it. Task-oriented leaders are ideal for some situations and person-oriented leaders are best for other situations.

Situational Favorability

Situational favorability in Fiedler’s model depends on three factors that determine how much control leaders have over group situations:

- Leader-member relations: The quality of relationships between leaders and followers – positive relationships provide more influence than poor relationships

- Task structure: How clear the goals, procedures, and performance standards are. Highly structured tasks provide clear guidance and evaluation criteria, while unstructured tasks involve ambiguity and require creative problem-solving

- Position power: The formal authority and influence resources available to leaders through their organizational positions

There are eight different degrees of situational favorability depending on the degree of leader-member relations, task structure, and position power. Fiedler’s research suggested that:

- Task-oriented leaders perform best in highly favorable situations (good relations, structured tasks, high power) and highly unfavorable situations (poor relations, unstructured tasks, low power)

- Relationship-oriented leaders perform best in moderately favorable situations

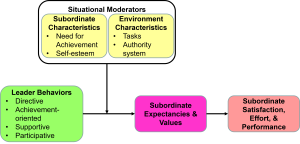

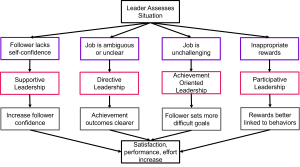

Path-Goal Theory

Path-Goal Theory (House, 1971) provides an alternative contingency approach focusing on how leaders can use their resources to complement follower work environments. This theory emphasizes leader flexibility and suggests that effective leaders can adapt their behavior to meet situational demands and follower needs.

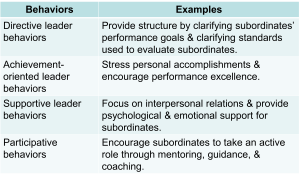

Four leadership behaviors in Path-Goal Theory include:

- Directive leadership: Providing guidance and structure

- Achievement-oriented leadership: Setting challenging goals and expecting high performance

- Supportive leadership: Showing concern for follower welfare

- Participative leadership: Involving followers in decision-making

Path-goal theory assumes that leaders are flexible and can change their style as situations require.

Situational factors that influence optimal leadership behavior include:

- Task characteristics (leaders should provide more direction when tasks are ambiguous)

- Follower characteristics (followers with high ability need less direction)

- Environmental factors

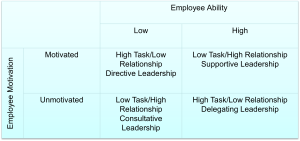

Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Leadership

Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Leadership (Hersey & Blanchard, 1977) model proposes that leadership effectiveness depends on follower maturity levels:

- Job maturity: Follower ability, skills, and knowledge relevant to task performance

- Psychological maturity: Self-confidence and self-respect

The model suggests that leaders should:

- Use directing styles for followers low in maturity

- Use coaching styles for moderate maturity

- Use supporting styles for higher maturity

- Use delegating styles for fully mature followers

As follower maturity increases, leaders should reduce both structuring and supportive behaviors, allowing the fully mature subordinate to be self-directed.

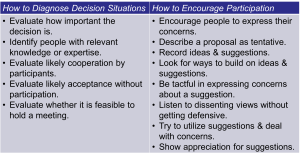

Vroom-Yetton Model

Vroom-Yetton Model (Vroom & Yetton, 1973) addresses when leaders should involve followers in decision-making processes. This normative model provides decision trees that specify appropriate participation levels based on decision importance, information distribution, goal congruence, and acceptance requirements.

Benefits of participative leadership include:

- Improved decision quality when followers possess relevant information

- Increased acceptance when follower buy-in is critical

- Enhanced motivation through involvement in decision processes

- Better understanding of circumstances requiring decisions

- Clearer objectives and plans

- Improved communication and conflict resolution

However, participation may be inappropriate when followers lack relevant expertise or when time pressures require quick decisions.

Media Attributions

- Team Leadership © Scott Maxwell is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Leadership & Personality © Jay Brown and Copilot

- Five Sources of Power © Jay Brown and Copilot

- Leadership Behavior Description Questionnaire

- Adaptive Leadership Styles

- Fiedler’s Contingency Theory of Leadership

- Situational Moderators in Path-Goal Leadership Theory adapted by Jay Brown

- Leader Behaviors and Examples in Path-Goal Theory

- Path-Goal Theory of Leadership adapted by Jay Brown

- Guidelines for Participative Leadership