15-1: Organizational Theory

Have you ever wondered why some workplaces feel like well-oiled machines where everything runs smoothly, while others feel chaotic and frustrating? Maybe you’ve worked at a fast-food restaurant where everyone knew exactly what to do and when to do it, versus a summer job where nobody seemed to know who was in charge of what. Or perhaps you’ve noticed how some companies seem to adapt quickly to changes – like how Netflix pivoted from DVDs to streaming – while others struggle to keep up and eventually disappear.

The answers to these workplace mysteries lie in how work is organized, and it’s way more fascinating and important than you might think.

Organizational Theory gives us a set of propositions to explain and predict how groups and individuals behave given different organizational structures and circumstances. Think of it as a toolkit for understanding why your workplace functions the way it does. The way work is structured, coordinated, and managed within organizations doesn’t just affect some abstract business metrics – it profoundly shapes your daily experience as an employee, affects how well companies perform, and even influences broader society.

Organizational Theory gives us a set of propositions to explain and predict how groups and individuals behave given different organizational structures and circumstances. Think of it as a toolkit for understanding why your workplace functions the way it does. The way work is structured, coordinated, and managed within organizations doesn’t just affect some abstract business metrics – it profoundly shapes your daily experience as an employee, affects how well companies perform, and even influences broader society.

Understanding how organizations work isn’t just academic busy work. It’s practical knowledge that’ll help you navigate your career, contribute more effectively to teams, and maybe even design better workplaces yourself someday. You might be thinking, “Why should I care about organizational theory when I just want a good job?” Here’s the thing: the most successful professionals aren’t just good at their specific tasks – they understand how their organizations work and how to help them work better.

Think about the difference between working at a startup where everyone wears multiple hats and decisions get made quickly around a kitchen table, versus working at a large corporation where there are detailed procedures for everything and decisions flow through multiple layers of management. Neither approach is inherently better – they’re just different ways of organizing work that fit different situations and goals.

The transformation of how we organize work reflects broader changes in society. We’ve seen technological advancement change everything from how we communicate to how we collaborate. Globalization means your coworker might be in another country entirely. Demographics are shifting as different generations bring different expectations to work. And let’s be honest – what employees expect from their jobs has changed dramatically over the past few decades.

The COVID-19 pandemic threw a curveball that accelerated many organizational changes that were already happening. Almost overnight, companies had to figure out remote work, virtual collaboration, and distributed organizational structures. These changes challenged traditional assumptions about how work should be organized and opened up new possibilities for how we think about the workplace. You’ve probably experienced this firsthand if you’ve worked remotely or in a hybrid setup.

Understanding organizational dynamics requires looking at multiple levels – from how individual jobs are designed, through group processes, to organizational culture and strategy. These levels all interact in complex ways that create emergent properties you can’t predict by understanding any single level alone. It’s like how a jazz band creates music that’s more than just the sum of individual musicians playing their parts.

Classical Organizational Theory

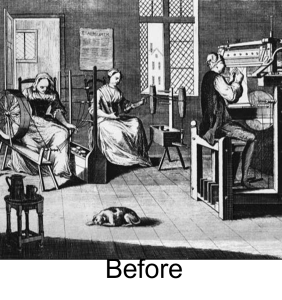

Let’s start our journey by understanding where organizational thinking began. Picture this: it’s the 1700s, and the Industrial Revolution is completely changing how people work. Before this time, most work was done by individuals or small groups of craftspeople. Suddenly, people were trying to figure out how to coordinate hundreds or thousands of workers in these massive new manufacturing enterprises. Talk about a challenge nobody had faced before!

Classical organizational theory emerged during this period, and it reflects the mindset of that era. You can almost imagine these early theorists looking at these new factories and thinking, “How do we make this whole thing run like a machine?”

Four basic principles shaped classical theory, and they tell you a lot about how people thought about work back then. First, organizations exist primarily for economic reasons – to maximize efficiency and output. Everything else was considered secondary to making money and producing goods efficiently. Pretty straightforward, right?

Second, scientific analysis could identify the “one best way” to organize for production. This reflected tremendous faith in rational analysis and the scientific method to solve organizational problems. The assumption was that if you studied hard enough, you could discover optimal organizational designs that would work universally. It’s kind of like thinking there’s one perfect recipe for chocolate chip cookies that everyone would love.

Third, specialization and division of labor would maximize production by letting people develop expertise in narrow areas while reducing the complexity of individual jobs. Instead of one person making an entire product, you’d break it into simple, repetitive tasks that anyone could learn quickly. Think assembly line work.

Fourth, both people and organizations act according to rational economic principles. This assumed that people are motivated primarily by money and will behave predictably when you provide the right economic incentives. If only human motivation were that simple!

The mechanistic view that characterized classical theory assumed organizations should operate like machines, with people and technology serving as interchangeable components. The emphasis was on predictability, control, and efficiency while minimizing variation and individual differences that might disrupt smooth functioning. You can see how this might make people feel like cogs in a wheel, can’t you?

Scientific Management

Frederick Winslow Taylor’s Scientific Management represents one of the most influential applications of these classical principles (Taylor, 1916/1996). Taylor was absolutely obsessed with finding the “one best way” to perform work through systematic analysis of job requirements and worker capabilities. Picture a guy with a stopwatch timing everything workers did, trying to optimize every single movement.

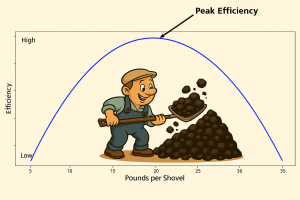

Here’s where it gets interesting: Taylor’s famous shoveling study at Bethlehem Steel perfectly illustrates his methodology. Taylor noticed that workers used greatly different loads on their shovels and wondered if there was an optimal load size. So what did he do? He conducted systematic experiments, paying employees to shovel for specified periods with varying loads – basically paying people to be guinea pigs in his efficiency experiments.

His analysis revealed that efficiency varied dramatically based on shovel load size, leading him to standardize optimal load weights. The results? Productivity increased significantly, and workers earned more money because they were paid per ton moved. It was a win-win, at least on the surface.

Taylor (1916/1996) developed four principles that provide his systematic approach. First, management should study the best workers to understand superior performance methods. Second, this knowledge should be reduced to laws and rules that can be taught to other workers. Third, workers should be carefully selected and trained to implement optimal methods. Fourth, work should be redistributed so management handles planning and coordination while workers focus on execution.

You might be thinking this sounds pretty reasonable, and in many ways it was revolutionary for its time. But you can probably also see how this approach might make work feel pretty mechanical and impersonal.

Bureaucracy

Max Weber’s Bureaucracy provides a complementary perspective on organizational structure (Weber, 1947). Weber, a German sociologist, studied large, efficient organizations like the Roman Empire, Prussian Army, and Catholic Church to identify common characteristics that enabled their effectiveness and longevity. Think about it – these organizations lasted for centuries or even millennia. They must have been doing something right!

Weber’s motivation included social protest against the favoritism and nepotism that characterized many organizations of his time. He viewed bureaucracy as a rational, merit-based alternative to traditional authority systems based on personal relationships or inherited status. In Weber’s ideal bureaucracy, your job and advancement would depend on your qualifications and performance, not who you knew or what family you came from. Pretty progressive thinking for the early 1900s!

Weber (1947) identified four key dimensions of bureaucratic organization. Division of labor creates specialized positions with specific responsibilities, enabling organizations to benefit from individual talents while avoiding problems where people perform tasks they’re not qualified for. Makes sense – you wouldn’t want your accountant performing surgery or your surgeon doing your taxes.

Delegation of authority establishes clear lines of responsibility where supervisors assign specific tasks to employees and hold them accountable for completion. This requires managers to provide appropriate authority along with responsibility while avoiding micromanagement. You know those managers who try to control every little detail? Weber would not approve.

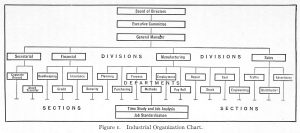

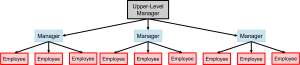

Top-down hierarchical structure creates clear authority relationships and communication channels that enable coordination and control. Everyone knows who reports to whom and how decisions get made. Span of control refers to how many subordinates report to each supervisor. Finding the right span balances supervision quality with administrative efficiency – too few subordinates wastes management time, but too many makes effective supervision impossible.

Additional bureaucratic elements include standardization of tasks, specialization of labor, and centralization of decision-making. Think about how military organizations operate – everyone has a clear role, follows established procedures, and knows exactly who has authority to make different types of decisions.

Now, before you start thinking bureaucracy sounds pretty good, let’s talk about the criticisms. Criticisms of classical theory point out that it treats people essentially like programmed responses to organizational stimuli while ignoring the human element. Classical theory assumes universal principles work regardless of circumstances and fails to recognize that people’s behavior can actually influence how organizations should be configured.

Holacracy represents a contemporary alternative that’s worth knowing about. It distributes authority and decision-making throughout self-organized teams rather than traditional hierarchical positions. Instead of having a boss tell you what to do, employee roles are defined by goals and responsibilities, organized into circles with clearly defined purposes and governance processes. Some companies like Zappos have experimented with holacratic systems, though results have been mixed. It turns out getting rid of traditional management is harder than it sounds!

Contingency Organizational Theories

As researchers studied more organizations, they began to realize something important: classical theory’s “one best way” approach didn’t always work. Have you ever noticed how what works great in one situation might be a disaster in another? That’s exactly what these researchers discovered.

Contingency theories emerged with the revolutionary idea that optimal organizational structure depends on situational factors – there isn’t one universal solution that works everywhere. It’s like realizing there’s no single perfect outfit that works for every occasion. What you wear to a job interview is different from what you wear to a music festival, right?

Woodward’s Technology-Based Framework

Joan Woodward identified three types of organizations based on production technology, and her findings were pretty eye-opening (Woodward, 1958). Small-batch organizations produce specialty products one at a time, like custom furniture or specialized consulting services. These typically require high skill levels and flexible coordination because every project is different.

Large-batch and mass-production organizations produce large numbers of identical units through assembly-line operations, like car manufacturing or food processing. These emphasize standardization and efficiency through predictable, repetitive processes. Think McDonald’s – every Big Mac should be essentially the same whether you buy it in New York or California.

Continuous-process organizations depend on continuous processes for output, like oil refineries, chemical plants, or power generation facilities. These require different coordination mechanisms because the production process can’t easily be stopped and started. You can’t just shut down a nuclear power plant for lunch break!

Span of control variations across these technology types reflect different coordination needs. Small-batch organizations often need smaller spans of control due to complex coordination requirements, while mass-production organizations can support larger spans due to standardized processes.

Lawrence and Lorsch’s Environmental Framework

Lawrence and Lorsch proposed something that makes intuitive sense once you think about it: environmental stability dictates optimal organizational forms (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967). Organizations in stable environments tend toward mechanistic structures that depend on formal rules and regulations, centralized decision-making, and smaller spans of control.

Organizations in unstable or rapidly changing environments develop organic structures characterized by larger spans of control, less formal procedures, and decision-making at middle organizational levels that enables rapid adaptation. Think about the difference between a government agency (stable environment, mechanistic structure) and a tech startup (unstable environment, organic structure). The government agency can afford to have lots of rules and procedures because things don’t change much day to day. The startup needs to be able to pivot quickly when market conditions change.

Here’s where it gets really interesting: departmental variations within single organizations reflect different environmental demands. A company’s R&D department might need organic structure due to rapidly changing technology, while the manufacturing department benefits from mechanistic structure that provides stability and efficiency. This means the same company might need different organizational approaches in different departments!

Integration requirements become critical when organizations include both organic and mechanistic departments that must coordinate their activities. Companies must develop solutions that accommodate different structural needs while maintaining overall coordination. It’s like trying to coordinate between the creative team that thrives on chaos and the accounting team that needs everything documented and filed properly.

Mintzberg’s Organizational Configurations

Mintzberg’s organizational configurations provide a comprehensive framework identifying five basic organizational types that represent different ways of coordinating work and distributing authority based on strategy, environment, technology, and size (Mintzberg, 1979). This framework helps organizations understand which structural approach best fits their particular circumstances and strategic objectives.

Human Relations Organizational Theory

By the mid-1900s, people began questioning classical theory’s mechanistic assumptions and their tendency to create boring, unchallenging jobs. You might have experienced this yourself if you’ve ever had a job where you felt like a robot going through the motions. Human relations theory emerged with the revolutionary idea that how managers think about their employees significantly influences how they treat those employees, creating self-fulfilling prophecies.

The employee motivation focus distinguishes human relations theory by addressing employee goals and aspirations rather than simply economic incentives. This perspective suggests that organizational success depends on relationships and motivation, not just structural arrangements and economic rewards. Turns out people are more complicated than just wanting a paycheck!

McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y

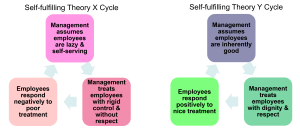

McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y illustrates how managerial assumptions about employee nature influence management practices and subsequently affect employee behavior. This is where it gets really interesting because it shows how our beliefs about people can become reality.

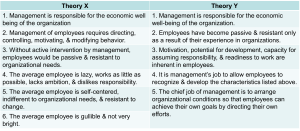

Theory X assumes employees are inherently lazy, self-serving, uninterested in working, and lacking ambition and intelligence. Managers operating under Theory X assumptions tend to use directive supervision, extensive controls, and external motivation. If you’ve ever had a micromanaging boss who watched your every move, you’ve probably encountered Theory X thinking.

Theory Y emphasizes the inherent goodness, capabilities, and potential of employees, assuming that management must provide opportunities for growth and development. Theory Y managers tend to use participative approaches, provide autonomy, and create conditions for intrinsic motivation. These are the managers who trust you to get your work done and focus on supporting your success.

Here’s the kicker: self-fulfilling prophecy effects occur when managerial expectations influence employee behavior in directions that confirm initial assumptions. If you treat someone as untrustworthy, they may become less trustworthy. If you treat them as capable and motivated, they may develop greater capabilities and motivation.

Think about teachers you’ve had – did the ones who believed in your potential help you perform better than those who seemed to expect you to fail? That’s the self-fulfilling prophecy in action, and it’s incredibly powerful in workplace settings.

Systems Theory of Organizations

Systems theory views organizations as complex entities that develop and change over time through internal and external forces rather than self-contained entities that can be understood in isolation. This perspective emphasizes that the organization is not a self-standing entity but constantly interacts with its environment.

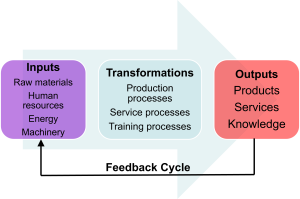

The input-transformation-output model provides the basic framework, and it’s actually pretty straightforward once you get it. Inputs include materials, labor, capital, information, and other resources that organizations acquire from their environments. Transformations represent the processes through which organizations convert inputs into outputs, adding value through these conversion processes. Outputs include products, services, and other results that organizations provide to their environments.

The Apple Example

Let’s use Apple to illustrate how systems theory works in practice. Apple inputs materials like plastic, alloys, and computer chips, along with labor from engineers, assemblers, and sales staff, plus capital from investors and profits from product sales. The company transforms these inputs into iPhones through design, manufacturing, and marketing processes that must create added value to the inputs.

Apple outputs iPhones to consumers while also producing intangible outputs like prestige, employee morale, and investor confidence. The revenue from iPhone sales becomes additional input that sustains the system through feedback loops, while customer satisfaction information guides future product development.

Here’s where it gets cool: system interconnections extend beyond individual organizations. Apple’s relationship with wireless carriers enhances the value of both systems through complementary capabilities and mutual dependence. Your iPhone wouldn’t be nearly as useful without Verizon, AT&T, or other carriers, and those carriers need popular devices like iPhones to attract customers.

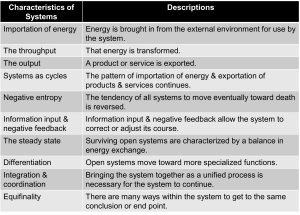

Important characteristics of open systems include several features that distinguish systems approaches from mechanistic perspectives. Negative entropy refers to organizations’ ability to continue importing energy to maintain life rather than experiencing entropy or death that would occur in closed systems. Information input through feedback loops enables organizations to monitor performance and adjust operations based on environmental changes. Equifinality suggests that organizations can achieve desired outcomes through multiple pathways rather than single “one best way” approaches.

Media Attributions

- Industrial Organization Chart 1921 © William O. Lichter is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Global Network Connectivity © Mohamed Hassan is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Cottage Industry © History Crunch

- The Rise of Structured Work in Industrial Organizations © Regulatory Transparency Project

- Frederick Taylor © Gessford is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Peak Efficiency © Jay Brown and Copilot

- Max Weber © Ernst Gottman is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bureaucracy adapted by Jay Brown

- McGregor’s Theory X & Y adapted by Jay Brown

- Contrasting Views of Workforce Motivation

- Systems Theory of Organizations adapted by Jay Brown

- The Cycle of Systems Theory adapted by Jay Brown

- Key Characteristics of Systems Theory in Organizational Contexts