2-2: Descriptive Research Methods

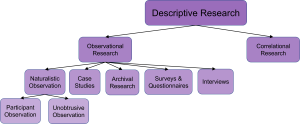

Now let’s dive into the nuts and bolts of how we actually study workplace behavior. Descriptive methods are like taking detailed photographs of organizational life — they involve neither random assignment nor manipulation of variables. Instead, they capture what’s happening without trying to control or change anything. There are two main types: observational research and correlational research.

Now let’s dive into the nuts and bolts of how we actually study workplace behavior. Descriptive methods are like taking detailed photographs of organizational life — they involve neither random assignment nor manipulation of variables. Instead, they capture what’s happening without trying to control or change anything. There are two main types: observational research and correlational research.

While you can’t establish causation with descriptive research, these methods are often inexpensive and make use of available resources, making them very practical for organizations. They eliminate the ability to make causal inferences, but they’re still incredibly important because they can describe relationships effectively. There’s a great deal to be gained from accurate description, and descriptive research can still be very useful for predicting behavior, even without understanding causation.

Think of descriptive research as detective work. You’re gathering clues about workplace phenomena, looking for patterns that might explain why some organizations thrive while others struggle, or why certain employees excel while others barely get by. Like any good detective, you need multiple types of evidence to build a convincing case. In most cases, the most feasible approach to data collection for I/O psychologists is field research, an approach in which evidence is gathered in a “natural” setting, such as the workplace (Spector, 2001).

Observational Research Overview

Observational research comes in several flavors, each with its own advantages and blind spots:

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation involves watching behavior in its natural environment without interfering — kind of like being a workplace anthropologist. You might sit in on meetings, observe team interactions, watch how employees use shared spaces, or notice communication patterns during busy versus slow periods. The goal is to see authentic behavior that hasn’t been influenced by the research process.

This approach can reveal fascinating insights that would never emerge from surveys. For example, you might notice that the most productive teams take more frequent breaks, that certain seating arrangements encourage collaboration, or that informal conversations in the break room actually serve important organizational functions.

Participant Observation

Participant observation takes this approach a step further — the observer tries to blend in completely with those being observed. Maybe I/O psychologists should actually get a job for a few years to truly blend in and understand workplace dynamics from the inside. This approach can reveal insider perspectives that would never emerge in surveys or interviews — the unwritten rules, hidden conflicts, informal power structures, and cultural nuances that outsiders miss.

However, participant observation raises obvious ethical questions about disclosure and consent, plus there are potential bias issues when researchers become personally invested in the organizations they’re studying.

Unobtrusive Observation

Unobtrusive observation involves trying to objectively and unobtrusively observe behavior without blending in with the group. Jane Goodall spent many years learning to become an unobtrusive observer of chimpanzee behavior, demonstrating the patience and skill this approach requires. This method can capture more natural behavior patterns because subjects aren’t trying to impress or please the researcher.

The digital age has created amazing new opportunities for unobtrusive observation. Organizations can now analyze massive datasets about employee behavior — who collaborates with whom, how long people spend in different types of meetings, when and where people are most productive, or how workplace changes affect movement and interaction patterns.

Here’s a critical issue with all observational research: Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle from physics states that the act of observing something has the effect of changing it. The implication is that we can never know complete “truth” because observation itself affects what we’re trying to study. Ever notice how differently people behave when they know the boss is watching? That’s this principle in action.

Case Studies

Case studies involve detailed examination of a particular individual, group, company, or society. You might study the professional history of a famous CEO, analyze how a particular organization handled a crisis, or examine an exceptional team’s success factors. Netflix’s transformation from a DVD-by-mail company to a streaming giant would make a fascinating case study, revealing how organizations can completely reinvent themselves.

Case studies are very beneficial for description and providing rich details about typical or exceptional firms or individuals. They can provide incredibly detailed insights that you’d never get from surveys or experiments. They’re particularly valuable for studying unique situations, exploring new phenomena, developing hypotheses for larger studies, or understanding complex processes that unfold over time (Locke & Golden-Biddle, 2002).

However, generally in science we prefer to know general truths about large groups of individuals, and a case study may reveal only specific truths that aren’t generalizable to other situations. The organizations, people, markets, and contexts are all different from case to case. Case studies are costly but allow researchers to examine behavior very deeply. They’re sometimes used when “unique” individuals are hard to find (like people with specific types of brain damage).

Be careful — case studies should not be used to make broad general statements about all organizations or all people. They’re great for generating ideas and understanding possibilities, but they can’t tell us how broadly their findings apply.

Archival Research

Archival research relies on secondary data sets collected by other people for general or specific purposes. This approach can be incredibly cost-effective and allows you to examine long-term trends that would be impossible to study in real-time. Plus, you can often access huge datasets spanning many years or covering thousands of employees.

The quality of archival research is heavily affected by the strength of the original data set, and researchers have very little control over data quality or what variables were included. FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act) and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) laws can significantly limit access to sensitive information, particularly in educational and healthcare settings.

Archival datasets usually include both cross-sectional data (snapshots at one point in time) and longitudinal data (the same variables measured repeatedly over time), which can be incredibly valuable for understanding how workplace phenomena change and develop.

Want to know whether diversity training actually improves workplace climate? You might analyze employee satisfaction surveys, turnover rates, promotion patterns, and discrimination complaints before and after training programs were implemented. The beauty of archival research is that the data already exists — no need to design surveys, recruit participants, or wait for longitudinal effects to emerge.

Self-Administered Questionnaires and Surveys

Self-administered questionnaires are surveys completed by respondents in the absence of an investigator. They’re commonly used in both laboratory and field research, and you should always consider the rate of return and who actually returns them — this can dramatically affect your results.

Questionnaires are useful for three main reasons: they’re easy to administer, you can administer them to large groups at one time, and they can provide respondents with anonymity (which encourages honest responses on sensitive topics).

Technological Advances

Technological advances have revolutionized survey research in exciting ways:

Web-based surveys allow participants to answer questions quickly, easily, and on their own time. They can include multimedia elements, complex branching logic, and real-time data analysis.

Experience sampling methodology (ESM) captures momentary attitudes and psychological states throughout the day using smartphone apps. Instead of asking “How stressed are you at work in general?” researchers can ping participants multiple times daily asking “How stressed are you right now?” This approach is particularly popular for studying emotions at work because it captures their dynamic, fluctuating nature (Gabriel et al., 2019). ESM involves asking participants to report on their thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and/or environment on multiple occasions over time in their natural settings (Hektner et al., 2007).

Online panels (a form of crowdsourcing) serve as online marketplaces where employers hire workers for single tasks or short-term assignments. Platforms like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk provide access to diverse participant pools but also raise questions about data quality and attention.

Survey Considerations

Questionnaires and surveys allow you to look at many cases in less depth, attempting to learn the opinions of large groups using smaller samples. However, you must get a representative sample — if not, then the survey results are meaningless regardless of how many people responded.

The importance of getting a random, representative sample is illustrated by the famous election polling disaster with Dewey and Truman in 1948. Pollsters surveyed thousands of people but got the wrong answer because their sample wasn’t representative of actual voters — they oversampled wealthy people who were more likely to support the Republican candidate.

Words used in surveys can be incredibly important and can completely change results. Only 27% of people approved of “government censorship of television,” but 66% said there should be “more restrictions on what is shown on television.” Same basic concept, different framing, completely different results.

People often don’t respond honestly to socially sensitive questions, as shown in beer consumption surveys where reported consumption is much lower than actual sales data would suggest. This social desirability bias affects many workplace topics like discrimination, unethical behavior, or conflicts with supervisors.

Interviews

Interviews involve an investigator asking a series of questions either verbally or in written form. They’re much more time-intensive than surveys, but they can generate incredibly rich data that questionnaires miss. However, you need to be careful that those interviewed represent a representative sample of the population you’re studying.

Interviews have clear benefits over questionnaires: response rates are typically higher because of the personal contact, and ambiguities about questions can be cleared up immediately through follow-up questions and clarification.

A skilled interviewer can explore unexpected responses and adapt their questioning strategy based on what they’re learning. Interviews can capture the complexity and nuance of workplace experiences in ways that multiple-choice questions never could.

Correlational Research

Correlational research involves investigators measuring one or more things (predictors) in order to make predictions about some other thing (criterion). For instance, you might use years of previous experience (predictor) to predict how successful a potential new employee will be (criterion). This approach is very commonly used for selection decisions in organizations.

While correlational research can’t establish causation, it’s incredibly valuable for practical applications. If you know that certain characteristics reliably predict job success, you can use this information to make better hiring decisions, even if you don’t fully understand why these relationships exist. In truth, knowledge of correlational laws is often enough in I/O psychology since the practical goal is often to make better decisions and improve organizational effectiveness, not necessarily to understand every underlying mechanism.

Media Attributions

- Descriptive Research Methods © Jay Brown and Copilot

- Descriptive Research Methods © Jay Brown

- Seal of the United States Bureau of the Census © United States Bureau of the Census is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Survey © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license