3-1: Job Analysis

Your best friend just landed what sounds like an amazing job at a hot startup. Great salary, cool office, free snacks — the works. But three months later, they’re miserable and looking for a new job. When you ask what went wrong, they say, “I had no idea what I was actually going to be doing. The job description said ‘dynamic team player for exciting challenges,’ but I spend most of my day entering data into spreadsheets that nobody ever looks at.”

Your best friend just landed what sounds like an amazing job at a hot startup. Great salary, cool office, free snacks — the works. But three months later, they’re miserable and looking for a new job. When you ask what went wrong, they say, “I had no idea what I was actually going to be doing. The job description said ‘dynamic team player for exciting challenges,’ but I spend most of my day entering data into spreadsheets that nobody ever looks at.”

Sound familiar? This scenario plays out thousands of times every day because organizations skip one of the most fundamental steps in managing people: job analysis. It’s the systematic detective work that figures out what jobs actually involve and what kind of people can do them well. Without it, hiring becomes a guessing game, training becomes random, and performance evaluation becomes… well, let’s just say “subjective” is putting it nicely.

Think of job analysis as the ultimate “behind the scenes” investigation of work. It’s like having a workplace anthropologist who studies every detail of what employees do, how they do it, when they do it, why they do it, and what personal qualities make someone excel in that role. Industrial Psychology (also known as Personnel Psychology) uses job analysis to get a complete picture of what a worker does so organizations can assign appropriate monetary value to the job and make informed decisions about hiring, firing, predicting success, performance appraisal, and training.

The Foundation of Everything

The Foundation of Everything

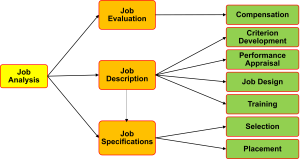

Here’s what makes job analysis so powerful: it forms the foundation of ALL other I/O psychology applications (Cascio & Aguinis, 2005). How can you evaluate someone’s performance if you don’t know what the job is supposed to involve? How can you hire the right person if you don’t understand what “right” looks like? How can you train people effectively if you don’t know what skills they actually need? It’s like having a GPS for human resource decisions — without it, you’re just driving around hoping you’ll somehow end up where you need to be.

The cool thing about modern job analysis is how it’s evolved from simple task lists (think “operates cash register,” “answers phone”) to sophisticated systems that can capture everything from the obvious (what someone does) to the subtle (how they think, what personality traits help them succeed, and how they interact with technology and other people) (Brannick et al., 2007). It’s like upgrading from a black-and-white TV to a 4K smart TV — same basic function, but infinitely more detailed and useful.

Why This Matters to You

But here’s why this matters to you personally: whether you’re planning to work in HR, become a manager, start your own business, or just want to understand your own career better, job analysis gives you a systematic way to think about work. You’ll be able to look at any position and break it down into its essential components, understand what makes someone successful, and even design better ways of organizing work. It’s like having X-ray vision for the workplace — you’ll see things that others miss and make better decisions because of it.

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

Before we dive into the how-to of job analysis, let’s get our terminology straight. Think of this as learning the building blocks — just like you need to understand atoms before you can understand molecules, you need to understand these basic concepts before you can master job analysis.

Elements, Tasks, and the Building Blocks of Work

Elements are the smallest unit of work activity that makes sense to analyze — think of them as the individual LEGO blocks of a job (Muchinsky, 2012). These are tiny, specific actions like grading, lecturing, data entry, opening email, or answering phone calls. You probably perform hundreds of elements every day without even thinking about them — they’re so automatic that they become invisible.

Here’s what’s interesting about elements: they’re usually so small and basic that they don’t tell you much about job requirements on their own. Knowing that someone “types on keyboard” doesn’t help you understand whether they need to be a creative writer, a data entry clerk, or a software programmer. Elements become meaningful only when you see how they combine into larger patterns.

Tasks are where things get more interesting — they’re multiple elements of work performed to achieve a specific objective (Brannick et al., 2007). Instead of just individual elements like “grading,” “lecturing,” and “data entry,” tasks would be “teaching undergraduate psychology courses,” “conducting original research,” “providing service to the university and profession,” or “assessing student learning outcomes.” Tasks are the level where work starts to make sense and where most job analysis focuses.

Here’s a useful way to think about it: if elements are like individual words, tasks are like complete sentences that express a complete thought and accomplish something meaningful. Tasks have a beginning, middle, and end — they’re complete units of accomplishment that people can understand and evaluate.

Positions vs. Jobs: Individual vs. Universal

This distinction trips up a lot of people, but it’s actually pretty simple once you get it. Positions are defined by the specific collection of tasks that one individual performs within an organization. Your position as a student is different from your classmate’s position, even if you’re both psychology majors, because you might have different part-time jobs, different research projects, different extracurricular responsibilities, or different course loads. A “Professor of Psychology” represents a specific position with unique combinations of teaching, research, and service responsibilities.

Jobs, on the other hand, are collections of positions that are similar enough to one another to share a common job title and general requirements (Sackett & Laczo, 2003). “Professor” would be a job that includes thousands of different positions across different universities, departments, and specializations. “College student” is a job that includes millions of different positions. Jobs are useful because they let us make generalizations and create systems that work across similar roles.

The distinction between positions and jobs is crucial for practical applications. If you’re analyzing positions, you get incredibly detailed information that’s perfect for that specific role but might not apply anywhere else. If you’re analyzing jobs, you get broader information that’s useful across many organizations but might miss important specifics.

KSAOs: The Human Side of Work

Now let’s talk about Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Other characteristics (KSAOs) — this is where job analysis gets really interesting because we’re moving from what work involves to what kinds of people can do it well (Cascio & Aguinis, 2005).

Knowledge refers to the facts, information, and understanding that someone needs to have to do the job effectively. Skills are the practiced abilities to do specific things that develop through experience. Abilities are more basic capacities that underlie skills — things like hand-eye coordination, mathematical reasoning, or verbal comprehension. Other characteristics include personality traits, interests, physical characteristics, and experiences that affect job performance.

Here’s a crucial point: a job analysis needs to focus on the position or the job, but not the exact person currently occupying the job. You’re analyzing what the work requires, not describing what the current job holder happens to bring to it (Muchinsky, 2012). This distinction is essential for avoiding bias and ensuring that job requirements reflect actual work demands rather than the personal characteristics of whoever happens to be doing the job right now.

Job Analysis Defined and Its Central Role

Job analysis is the process of defining a job in terms of its component tasks or duties and the knowledge, skills, and abilities required to perform them. More formally, it’s “a wide variety of systematic procedures for examining, documenting, and drawing inferences about work activities, worker attributes, and work context” (Sackett & Laczo, 2003, p. 21).

Think of job analysis as the cornerstone that supports virtually every decision organizations make about people. It forms the foundation of all other I/O psychology applications — recruitment, selection, training, performance management, compensation, and legal compliance all depend on accurate understanding of job requirements (Brannick et al., 2007).

Contemporary Challenges and Future Directions

Modern job analysis faces several challenges as work continues to evolve:

- Technology Integration: As jobs become more technology-dependent, job analysis must capture how humans interact with AI, automation, and digital tools.

- Remote and Hybrid Work: Traditional job analysis methods may need adaptation for distributed work environments where observation and interaction patterns differ significantly.

- Agile Organizations: Rapidly changing job requirements challenge traditional job analysis approaches that assume relatively stable work characteristics.

- Gig Economy: Non-traditional employment relationships require new approaches to understanding and analyzing work requirements.

Despite these challenges, job analysis remains fundamental to effective human resource management (Cascio & Aguinis, 2005). Organizations that invest in systematic job analysis continue to make better decisions about people, achieve better performance outcomes, and maintain stronger legal defensibility of their employment practices.

Media Attributions

- Stylized Man © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Job Analysis Defined © Jay Brown and Copilot

- Job Analysis © Jay Brown