3-2: Performing a Job Analysis

Common Methods of Data Collection

No matter what type of job analysis you’re performing, there are several common methods for gathering information. Each has its strengths and limitations, so smart practitioners often use multiple methods to get a complete picture (Brannick et al., 2007).

Observation: Seeing Work in Action

Observation is the earliest technique used — you simply watch incumbents perform the job and systematically document what you see. This method shows you what actually happens rather than what people think happens, but it can’t capture mental processes or rare but critical events.

The beauty of observation is that it shows you what actually happens rather than what people think happens or what they think you want to hear. Ever notice how people’s descriptions of their jobs sometimes don’t match what they actually do all day? Maybe they spend 40% of their time in meetings but describe themselves as “individual contributors.” Or maybe they say their job is “strategic planning” but actually spend most of their time putting out fires and solving immediate problems.

Observation cuts through this bias to reveal authentic work behavior (Wilson, 2007). You can see the interruptions, the informal problem-solving, the unwritten rules, and the workarounds that people develop but might not think to mention in interviews. You can observe the pace of work, the stress levels, the physical demands, and the social interactions that characterize the job.

However, observation has some obvious limitations that you need to understand. You can’t observe thinking, decision-making, planning, or other mental processes that might be crucial for job success. You also can’t observe rare but critical events through typical observation periods. Plus, there’s the fundamental problem that people often behave differently when they know they’re being watched.

Interviews: Accessing the Mental Side of Work

Interviews: Accessing the Mental Side of Work

Interviews, based on observation or discussion with HR personnel or managers, involve asking incumbents about their job responsibilities, challenges, and requirements. This method can access the mental aspects of work but may be subject to bias or incomplete recall (Franklin, 2005).

Interviews complement observation perfectly by accessing the mental aspects of work that you can’t see. Through skillful questioning, you can understand how people think about their work, what challenges they face, what strategies they use for success, and what knowledge and skills they consider most important.

The key to effective job analysis interviews is asking the right questions in the right way. Instead of general questions like “tell me about your job” (which often produces generic, public relations-type responses), try specific, behavioral questions like:

- “Walk me through exactly what you did yesterday from the moment you arrived until you left”

- “Describe a time when you had to handle a particularly challenging situation — what made it challenging and how did you handle it?”

- “What’s the most difficult part of your job, and what do you do to manage that difficulty?”

- “If you were training someone new to do your job, what would be the most important things to teach them?”

These specific, behavioral questions reveal much more useful information because they force people to think concretely rather than abstractly (Brannick et al., 2007). You get real examples, specific strategies, and insights into what actually matters for job success.

Critical Incidents: Learning from the Extremes

Critical Incidents technique asks incumbents to identify critical aspects of behavior or performance that led to success or failure. This helps focus on what really matters for job effectiveness rather than routine activities.

The critical incident technique is brilliant in its simplicity: ask people to describe specific examples of particularly effective or ineffective performance. Instead of getting abstract descriptions of job requirements, you get concrete stories that illustrate what really matters for success (Franklin, 2005).

This technique recognizes that not all job activities are equally important. Every job has routine tasks and critical moments — the moments that really determine success or failure. Critical incident technique helps you focus on what matters most rather than getting lost in the everyday minutiae that might not actually predict performance differences.

For example, instead of just knowing that “communication skills” are important for a manager, a critical incident might reveal that the best managers know how to deliver negative feedback in a way that motivates improvement rather than defensiveness. Or that excellent customer service representatives have a specific technique for de-escalating angry customers that involves acknowledging emotions before addressing problems.

Work Diaries: The Truth About Time

Work Diaries ask incumbents to keep detailed logs of their activities over specified periods. This provides objective data about time allocation but requires significant effort from participants (Wilson, 2007).

Work diaries provide objective data about how time is actually spent and what activities consume the most effort. This method can reveal surprising patterns that contradict both official job descriptions and people’s perceptions of their own work.

You might discover that people spend 30% of their time on activities that aren’t even mentioned in their job descriptions. Or that the activities described as “most important” in job descriptions actually consume very little time, while activities mentioned as “minor duties” take up most of the workday.

Questionnaires: Scaling Up the Analysis

Questionnaires ask incumbents about the frequency, importance, and other characteristics of various tasks or behaviors. This method enables systematic data collection from large numbers of people but may miss nuances that emerge from direct interaction (Muchinsky, 2012).

Questionnaires enable systematic data collection from large numbers of people, providing statistically reliable information about job characteristics. When you need to analyze multiple positions, compare jobs across different locations, or ensure that your findings are representative rather than based on a few individuals’ perspectives, questionnaires become essential for practical and economic reasons.

The standardization of questionnaire data enables sophisticated statistical analysis. You can identify which tasks are most critical, how much time is spent on different activities, what KSAOs are most important for success, and how these patterns vary across different contexts.

Approaches to Job Analysis

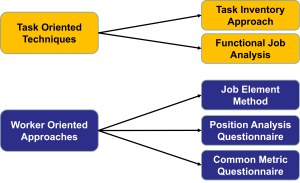

There are three main approaches to job analysis, each with different focuses and applications. Understanding these approaches helps you choose the right method for your specific needs and interpret results appropriately (Brannick et al., 2007).

Task-Oriented Approaches: The “What” of Work

Task-oriented approaches focus on describing the various tasks that are performed in specific jobs. They’re like creating a detailed documentary of workplace behavior, cataloging exactly what people do in their jobs.

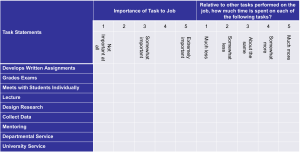

Task Inventory Approach

The task inventory approach involves generating comprehensive lists of task statements by Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) — individuals who are incumbents or experts regarding the target job (Franklin, 2005). Incumbents then indicate which statements describe their job and rate each task on dimensions like performance frequency, importance/criticality, and relative time spent.

For example, a task inventory for a college professor might include items like:

- “Develops and delivers undergraduate lecture courses”

- “Conducts original research in area of specialization”

- “Supervises student research projects”

- “Serves on departmental and university committees”

- “Reviews manuscripts for professional journals”

Task statements are typically rated by incumbents on several dimensions:

- Performance: Do you actually perform this task?

- Importance/Criticality: How important is this task for overall job success?

- Relative Time Spent: What percentage of your time is devoted to this task?

Advantages of task-oriented approaches include being relatively cheap and quick to administer, allowing data collection at respondents’ leisure, enabling surveys of many incumbents simultaneously, and producing results that are easily quantified and analyzed (Brannick et al., 2007).

Disadvantages include being time-consuming and expensive to develop initially, leaving ambiguities in items unresolved, focusing too narrowly on specific tasks (making it hard to compare across jobs and potentially missing important similarities), and requiring frequent updates as work processes change.

Functional Job Analysis (FJA)

Functional Job Analysis represents a more sophisticated task-oriented approach that obtains information about what tasks a person performs and how those tasks are performed (Fleishman & Reilly, 1992). FJA uses standardized task statements that are rated on three fundamental dimensions:

- Data: Extent to which cognitive resources are needed to handle information, facts, and ideas. This ranges from simple recognition and comparison up to complex analysis and synthesis.

- People: Extent to which interpersonal resources are needed. This dimension captures the social complexity of work, from minimal contact with others up to complex leadership and influence activities.

- Things: Extent to which physical resources are needed, including strength, speed, and interaction with equipment. This ranges from minimal physical activity up to complex manipulation of machinery or materials.

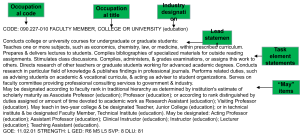

Functional Job Analyses were used to develop the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT), which contained basic information on 12,000 various jobs. The DOT coded jobs according to data, people, and things dimensions and contained a lead statement, task element statements, and “May” items to describe job requirements comprehensively.

O*NET: The Modern Evolution

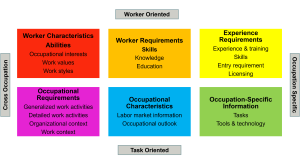

O*NET (Occupational Information Network) represents the modernization of the DOT for the internet age (Peterson et al., 1999). Developed by the Department of Labor to replace the aging DOT, O*NET is a comprehensive database of over 950 occupations that identifies and describes key components of modern work.

O*NET is accessible at http://onetcenter.org/ and provides a highly accessible, searchable online database based on data gathered through hybrid approaches that combine multiple data collection methods.

The O*NET Content Model is remarkably comprehensive, organizing occupational information into several major categories:

- Worker Characteristics: Abilities, interests, and work values

- Worker Requirements: Knowledge, skills, and education

- Experience Requirements: Training, credentials, and experience levels

- Occupational Requirements: Work activities and context

- Occupation-Specific Information: Specialized tasks and technology

Worker-Oriented Approaches: The “Who” of Work

Worker-oriented approaches examine the broad human behaviors and characteristics involved in work activities (Cascio & Aguinis, 2005). They focus on the physical, interpersonal, and mental aspects of work necessary for job completion, emphasizing what kinds of people can perform work effectively rather than what specific tasks are performed.

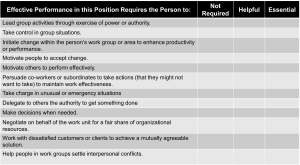

Job Element Method (JEM)

The Job Element Method focuses on identifying KSAOs necessary for effective performance. In this context, “element” means general work behaviors rather than specific task components (Fleishman & Reilly, 1992).

JEM uses SMEs to develop lists of job elements and provide work examples of each element. Importantly, JEM is specifically designed to identify KSAOs exhibited by superior candidates — the characteristics that distinguish excellent from average performers.

For example, JEM analysis of a College Professor position might identify elements such as:

- Knowledgeable about subject matter

- Skilled in interpretation of data

- Ability to communicate clearly, with subelements including:

- Can express ideas in an interesting manner to large groups of people

- Able to explain complex issues to students in one-on-one environments

The resulting profile provides behaviors and characteristics exhibited by successful job holders, which companies can use to identify and hire people with these qualities.

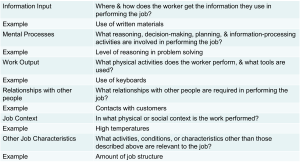

Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ)

The Position Analysis Questionnaire is a standardized instrument that focuses on general work behaviors rather than specific tasks (Muchinsky, 2012). It’s a self-report instrument completed by job incumbents containing 187 items that ask whether each item pertains to their job and how important it is.

Items are organized into six major dimensions:

- Information Input: Where and how does the worker get information needed to perform the job?

- Mental Processes: What reasoning, decision-making, planning, and problem-solving activities are involved?

- Work Output: What physical activities and tools are used to perform the work?

- Relationships with Others: What relationships with people are required?

- Job Context: In what physical and social environment is the work performed?

- Other Job Characteristics: What other activities, conditions, or characteristics are relevant?

Concerns about the PAQ include that it may not be suitable for all white-collar jobs, requires college-level reading ability, and is sometimes too abstract, making many different jobs appear similar in their profiles.

Common Metric Questionnaire (CMQ)

The Common Metric Questionnaire is a more recently developed instrument created by Harvey and colleagues to address PAQ limitations. The CMQ contains 2,077 items organized along 80 dimensions and takes approximately 3 hours to complete online (Brannick et al., 2007).

Key improvements over the PAQ include:

- Items are more behaviorally specified than PAQ items

- Lower reading level requirements

- Relevant for both managerial and non-managerial jobs

- More specific than PAQ but more abstract than task inventory approaches

Electronic Performance Monitoring: The Digital Age

Modern technology has enabled electronic performance monitoring that allows employers to monitor employee work activities continuously (Wilson, 2007). Examples include:

- Black boxes on airplanes that record “behaviors” leading up to incidents

- Customer support calls that “may be monitored for quality control”

- GPS tracking of drivers and delivery personnel

- Computer monitoring of keystrokes, screen time, and application usage

This technology enables job analysis to be performed without directly talking to incumbents or SMEs, providing objective behavioral data. However, electronic monitoring raises significant issues with employee privacy rights, and workers generally dislike these systems, which can affect both morale and the validity of the data collected.

Cognitive Task Analysis: Understanding Expert Thinking

Cognitive Task Analysis involves decomposing job and task performance into discrete, measurable units, with special emphasis on eliciting mental processes and decision-making strategies that distinguish expert from novice performance (Brannick et al., 2007).

Think-aloud protocols have been used by cognitive psychologists for years to investigate how experts think when they achieve high levels of performance. As workplaces become more technologically complex and knowledge-based, observable behavior alone can no longer fully explain successful performance.

This approach is particularly valuable for jobs involving complex problem-solving, decision-making under uncertainty, or expertise that develops over years of experience.

Personality-Based Job Analysis: The Person Behind the Performance

Personality-based job analysis systematically identifies personality requirements for different positions, recognizing that personality characteristics significantly influence job performance in many roles (Muchinsky, 2012).

This approach typically involves:

- Identifying behavioral requirements for effective performance

- Linking these behaviors to specific personality dimensions

- Using established personality frameworks (like the Five-Factor Model)

- Ensuring that personality requirements are demonstrably job-related

For example, a sales position might require high extraversion for client interaction, high conscientiousness for follow-through, and emotional stability for handling rejection.

Hybrid Methods: Getting the Best of Both Worlds

Hybrid approaches gather information about both work activities (tasks) and worker requirements (KSAOs) simultaneously (Peterson et al., 1999). These methods recognize that comprehensive job understanding requires both what people do and what kinds of people can do it effectively.

For example, for a snowcat operator at a ski resort:

- Task-oriented statement: “Operates Bombardier Snowcat, usually at night, to smooth out snow rutted by skiers and snowboard riders, and new snow that has fallen”

- Worker-oriented statement: “Evaluates terrain, snow depth, and snow condition and chooses the correct setting for the depth of the snow cut, as well as the number of passes necessary on a given ski slope”

Both types of information are necessary for comprehensive understanding of job requirements and effective human resource management.

Media Attributions

- Interviewing © Jay Brown and Copilot

- Task Inventory for College Professor © Jay Brown

- DOT Entry for College Professor © Dictionary of Occupational Titles

- O*NET Content Model © Jay Brown

- Types of Job Analysis © Jay Brown

- PAQ Dimensions & Elements

- Personality-based Job Analysis

- Understanding Jobs © Ashley Robinson is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license