4-1: Introduction to Predictors

Imagine you’re Netflix trying to decide which of a thousand new show ideas will become the next “Stranger Things,” or you’re an NBA team trying to figure out which college players will become superstars in the pros. Sounds tough, right? Well, that’s essentially what organizations face every single day when they’re hiring employees — they’re trying to predict future success based on limited information about candidates they barely know.

This is where predictors come in — they’re the tools and techniques we use to forecast who’s most likely to succeed in a job. Think of them as your crystal ball for employment decisions, except instead of mystical powers, they use systematic, scientific methods to peer into the future of job performance.

The Fundamental Challenge: Predicting the Unpredictable

Here’s the thing that keeps HR professionals up at night: selection is fundamentally about prediction (Murphy & Davidshofer, 2005). We’re trying to forecast who will succeed in jobs based on whatever scraps of information we can gather during the hiring process. If we had a time machine and could see exactly how every candidate would perform five years from now, hiring would be easy. But since we can’t travel through time (yet), we have to rely on the next best thing — systematic ways of gathering information that statistically relate to future job performance.

Every time you’ve applied for a job, you’ve encountered these predictors in action. That application asking about your experience? Predictor. The interview where they grilled you with behavioral questions? Predictor. Any tests or assessments you completed? All predictors. The organization was essentially building a case for whether you’d be successful, using whatever clues they could gather to make that crucial hiring decision.

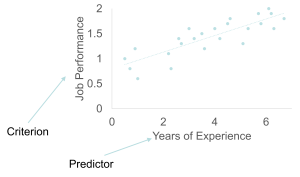

What makes this field both fascinating and maddening is the relationship between what we can measure during hiring (predictors) and what we actually care about (job performance). It’s like trying to predict who’ll be a great chef by watching them shop for groceries — sometimes the connection is obvious, sometimes it’s surprisingly counterintuitive.

The Importance of Predictors in Selection

Selection is fundamentally about prediction — forecasting who is likely to succeed in jobs based on available data (Guion, 1998). If we knew with certainty who was going to be a good performer, we wouldn’t need predictors at all. In effect, predictors forecast criteria (also known as job performance). Later on, during performance reviews, we will have actual data about the criterion (job performance) to help us make decisions about raises, promotions, or terminations.

Think about it this way: during the hiring process, we’re making bets about future performance based on whatever information we can gather. The better our predictors, the better our bets. Poor predictors lead to hiring mistakes — bringing in people who struggle or fail, while potentially rejecting candidates who would have been successful. Good predictors help us identify talent more accurately, leading to better performance, higher job satisfaction, and reduced turnover.

Understanding Tests and How They Work

What Exactly Is a Test?

Before we dive into specific types of predictors, let’s get clear about what we mean by “tests.” A test is a systematic procedure for observing behavior and describing it with the aid of numerical scales — essentially a device to quantify a hypothetical construct (Murphy & Davidshofer, 2005). Whether it’s the SAT, a personality questionnaire, or even a drug test, they’re all trying to quantify something about you that might predict how you’ll perform.

Tests are incredibly popular in both organizational and school settings because they provide standardized ways to compare people on important characteristics. The SAT attempts to measure college readiness, personality tests assess behavioral tendencies, and drug tests check for substance use that might affect job performance.

The Science of Test Development

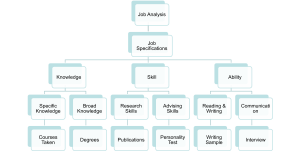

The process of creating good tests isn’t random — it follows a systematic approach rooted in job analysis and scientific methodology (Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2003):

- Begin with job analysis to understand what the job actually requires

- Identify criteria important for job success based on that analysis

- Identify KSAs (Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities) associated with those criteria

- Develop or find tests to tap these KSAs that have demonstrated validity

This systematic approach ensures that tests measure characteristics that actually matter for job performance rather than irrelevant factors that might lead to poor hiring decisions or legal problems.

For organizations looking to evaluate existing tests, resources like the Mental Measurements Yearbook provide comprehensive evaluations of tests across various areas. These evaluations include psychometric properties (reliability and validity), cost, administration time, and information on how to obtain them — essentially a consumer guide for psychological assessments.

Different Types of Tests: More Variety Than You’d Expect

Power vs. Speed Tests: Different Challenges, Different Insights

Tests can be classified along several important dimensions that affect what they measure and how they should be used (Murphy & Davidshofer, 2005):

Power tests have no fixed time limit or provide generous time allowances, but items become progressively more difficult. Most test takers are expected to finish all items, so performance depends on the complexity of problems you can solve rather than how quickly you work. The SAT is a classic example — while there are time limits, they’re designed to allow most students to attempt all questions, with difficulty increasing throughout each section.

Speed tests are composed of relatively easier items but impose strict time limits, with individuals told to complete as many items as possible. It shouldn’t be possible for anyone to finish all items in the allotted time. Typing tests exemplify this approach — the individual keystrokes aren’t intellectually challenging, but performing them quickly and accurately under time pressure represents the real skill being measured.

Here’s something interesting that assessment professionals have discovered: speed tests often yield greater variability among candidates, allowing for more effective prediction of job performance. This makes sense because most work involves performing reasonably familiar tasks under time pressure rather than solving impossibly difficult problems with unlimited time.

However, speed tests create legal complications under the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990). One of the most common accommodation requests is for additional time to complete tests. Organizations using speed tests must demonstrate that the type of speed required by the test is also required by the actual job, or they risk legal challenges from candidates with disabilities who need accommodations (Turner, DeMers, Fox, & Reed, 2001).

Individual vs. Group Testing: Quality vs. Efficiency

Individual tests are administered to one person at a time and can provide incredibly detailed information but are very costly in terms of time and money (Murphy & Davidshofer, 2005). A comprehensive cognitive ability test like the WAIS-III (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale) might take several hours to administer and requires a trained professional, but it provides an extraordinarily detailed picture of someone’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses.

Individual testing is like getting a custom-tailored suit — expensive and time-consuming, but perfectly fitted to the individual. Sometimes this level of detail is necessary, particularly for high-stakes decisions or when understanding specific cognitive patterns is crucial for job placement or accommodation decisions.

Group tests allow many applicants to be tested simultaneously, making them much cheaper to administer but potentially at a loss of precision. Examples include cognitive ability tests like the Wonderlic Personnel Test or the historical Army Alpha and Beta tests that could assess hundreds of people at once.

Group testing is like buying off-the-rack clothing — more efficient and cost-effective, but with less individual customization. For most organizational selection purposes, the efficiency gains outweigh the precision losses, especially when combined with other selection methods.

Paper-and-Pencil vs. Performance Tests

Paper-and-pencil tests (including their computer-based equivalents) represent the most typical kind of assessment, where individuals respond to a series of items in a test booklet or on a screen (Guion, 1998). Examples include the SAT, GRE, and most personality inventories. These tests are efficient to administer and score, making them practical for large-scale selection programs.

Performance tests require the manipulation of an object or piece of equipment, directly assessing someone’s ability to perform job-relevant tasks. Examples include flight simulators for pilots, pegboard tests for manual dexterity, or having a dental assistant candidate prepare a syringe of Novocain for administration. In these cases, the candidate’s skill in performing these tasks may be as important as their knowledge of how to carry out the actions.

Performance tests often have higher face validity — they look more obviously related to job requirements — but they’re also more expensive and time-consuming to develop and administer. They’re most valuable when physical skills or hands-on competencies are central to job success.

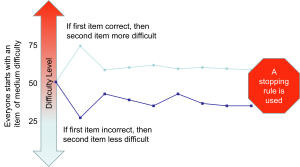

Computer Adaptive Testing: The Future Is Here

This is where technology gets really exciting for assessment. Computer Adaptive Testing (CAT) involves computer technology that identifies easier or harder questions to eventually estimate an applicant’s true ability level (Scroggins, Thomas, & Morris, 2008). The score on earlier questions affects the difficulty of subsequent questions, creating a personalized testing experience that adapts in real-time to each candidate’s performance.

Here’s how it works: if you answer a question correctly, the computer gives you a more difficult question next. If you answer incorrectly, it gives you an easier question. This process continues throughout the test, with the computer constantly refining its estimate of your true ability level based on which questions you can and cannot answer correctly.

CAT offers several significant advantages over traditional fixed-form testing:

- Quick and accurate scoring — results are available immediately

- More precise measurement — the test adapts to your specific ability level

- Finer discrimination — particularly effective for candidates at the high and low ends of ability scales

- Reduced testing time — achieves the same precision as longer traditional tests

- Enhanced security — each person gets a different set of questions, making cheating much more difficult

Real-world applications of CAT are expanding rapidly. Researchers have described CAT systems for assessing musical aptitude, dermatology expertise, and conflict resolution skills. CAT has been implemented for professional certification exams for CPAs and architects. The U.S. Navy has developed a CAT personality assessment for predicting performance in military jobs.

The sophistication of modern CAT systems allows them to balance multiple constraints simultaneously — ensuring content coverage across different areas while optimizing measurement precision and maintaining appropriate difficulty levels. This technology represents a significant advancement in our ability to efficiently and accurately assess human capabilities for selection purposes.

The Evolution and Impact of Testing

The development of systematic testing represents one of psychology’s greatest contributions to practical human resource management (Scroggins et al., 2008). From the Army Alpha and Beta tests of World War I to today’s sophisticated computer adaptive assessments, testing has evolved to become more precise, more fair, and more closely aligned with actual job requirements.

Modern organizations rely heavily on tests because they provide:

- Standardized comparisons across candidates from different backgrounds

- Objective data that supplements subjective impressions from interviews

- Legal defensibility when properly validated and job-related

- Efficiency in processing large numbers of candidates

- Predictive validity that improves hiring decisions

However, testing also raises important considerations about fairness, privacy, and the appropriate use of assessment data (Turner et al., 2001). As we’ll explore throughout this module, effective use of predictors requires balancing scientific rigor with ethical responsibility and legal compliance.

The key insight for understanding predictors is that they’re tools for making better decisions about people — not perfect tools, but systematically better than intuition, gut feelings, or random selection (Guion, 1998). When properly developed, validated, and applied, predictors help organizations identify talent more effectively while treating candidates fairly and respecting their dignity as individuals.

As we move forward in this module, we’ll explore the specific types of predictors available, their strengths and limitations, and how they can be combined to create effective selection systems that serve both organizational needs and individual aspirations for meaningful, successful careers.

Media Attributions

- Predictors Relate to Criterion © Jay Brown

- Types of Predictors © Jay Brown

- CAT and Stopping Rules © Jay Brown