4-3: Predictors Based on Stable Worker Traits

Cognitive Ability: The Powerhouse Predictor

Cognitive Ability: The Powerhouse Predictor

Why Intelligence Tests Dominate Selection

There’s overwhelming evidence that cognitive ability is the single best predictor of job performance across most jobs (Gottfredson, 1997; Schmidt & Hunter, 1981). It’s not just that smart people perform better — it’s that cognitive ability predicts performance consistently across different jobs, organizations, and even countries.

The correlation between cognitive ability and job performance is typically around .53, which means intelligence explains about 25% of the variance in how well people do their jobs (Schmidt & Hunter, 1981). That might not sound like much, but in the world of psychological prediction, it’s huge. For comparison, most personality traits correlate with performance around .20-.30.

General cognitive ability is considered by many as the most important predictor because evidence suggests that it:

- Accounts for a large proportion of variance in criterion performance

- Predicts performance similarly across countries and cultures

- Remains valid across diverse job types and organizational contexts

However, specific cognitive abilities also matter, depending on the specific job requirements identified through job analysis.

The Army Alpha and Beta Legacy

The story of cognitive ability testing begins with World War I and the development of the Army Alpha and Beta mental ability tests by Yerkes (who was President of the American Psychological Association at the time). Facing the massive challenge of sorting millions of soldiers into appropriate roles, the military turned to psychologists for help.

Based on the pioneering work of Binet, these tests operated under the principle that “the proper use of manpower, and more particularly of mind or brain power, would assure ultimate victory.” The Alpha test assessed literate soldiers with verbal and reasoning problems, while the Beta provided nonverbal assessments for those with limited English skills.

The purpose and goals of the Army Alpha and Beta tests were revolutionary for their time:

- Mass Assessment: First systematic attempt to assess mental ability on such a massive scale

- Efficient Sorting: Quickly identify soldiers’ intellectual capabilities for appropriate job assignment

- Scientific Approach: Apply psychological principles to practical military needs

- Standardization: Create consistent assessment procedures across different locations and administrators

This was revolutionary — the first time anyone had attempted systematic mental ability assessment on such a massive scale. The success of these tests proved that psychological assessment could work practically and laid the foundation for all modern cognitive testing.

The Alpha test included eight different types of problems:

- Following oral directions

- Arithmetic reasoning

- Practical judgment

- Synonym-antonym vocabulary

- Disarranged sentences

- Number series completion

- Analogies

- Information

The Beta test was designed for illiterate soldiers or those with limited English proficiency and included:

- Maze completion

- Cube analysis

- X-O series

- Digit symbol coding

- Number checking

- Picture completion

- Geometrical construction

These tests demonstrated that cognitive ability could be assessed systematically and used effectively for personnel decisions, establishing the foundation for modern employment testing.

Modern Cognitive Ability Tests

The Wonderlic Personnel Test has become famous partly through NFL draft coverage, where fans obsess over quarterback scores and analyze how cognitive ability might relate to performance under pressure. The Wonderlic packs a cognitive assessment into just 12 minutes, making it practical for mass screening while still providing meaningful prediction of job performance.

The Wonderlic contains 50 questions that must be completed in 12 minutes, covering:

- Verbal reasoning: vocabulary, analogies, reading comprehension

- Mathematical reasoning: arithmetic, algebra, geometry

- Logical reasoning: number series, spatial relationships

What makes the Wonderlic particularly useful is its brevity and strong correlation with longer, more comprehensive cognitive ability tests. Research shows that Wonderlic scores correlate highly with other measures of general intelligence while requiring minimal testing time and administrative resources.

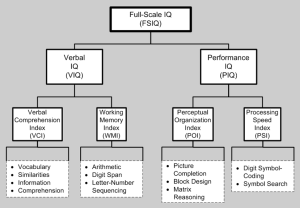

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) represents the other extreme — a comprehensive, individually administered test that takes hours to complete but provides incredibly detailed information about different cognitive abilities. The WAIS reveals something important about intelligence — it’s not just one thing. People can be strong in verbal reasoning but weak in spatial skills, or quick at processing simple information but slow at complex problem-solving.

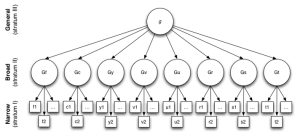

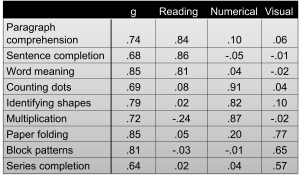

Carroll’s Three-Stratum Model provides a sophisticated framework for understanding cognitive abilities, organizing them into three hierarchical levels:

- Stratum III: General intelligence (g factor) at the top

- Stratum II: Broad cognitive abilities (fluid intelligence, crystallized intelligence, etc.)

- Stratum I: Narrow cognitive abilities (specific skills and knowledge areas)

This model helps explain why general cognitive ability predicts performance across diverse jobs while specific cognitive abilities become more important for particular roles.

The WAIS includes multiple subtests that assess different cognitive capabilities:

Verbal Subtests:

- Information: General knowledge acquired from culture (e.g., “Who is the president of Russia?”)

- Comprehension: Ability to deal with abstract social conventions and expressions (e.g., “What does ‘Kill 2 birds with 1 stone’ mean?”)

- Arithmetic: Concentration while manipulating mental mathematical problems (e.g., “How many 45¢ stamps can you buy for a dollar?”)

- Similarities: Abstract verbal reasoning (e.g., “In what way are an apple and a pear alike?”)

- Vocabulary: Degree of learned and expressed vocabulary (e.g., “What is a guitar?”)

- Digit Span: Attention and concentration (e.g., repeating digits forward: 1-2-3, backward: 3-2-1)

- Letter-Number Sequencing: Attention and working memory (e.g., given Q1B3J2, arrange numbers numerically then letters alphabetically)

Performance Subtests:

- Picture Completion: Ability to quickly perceive visual details

- Digit Symbol-Coding: Visual-motor coordination and processing speed

- Block Design: Spatial perception and visual problem solving

- Matrix Reasoning: Nonverbal abstract problem solving and spatial reasoning

- Picture Arrangement: Logical reasoning and social insight

- Symbol Search: Visual perception and speed

- Object Assembly: Visual analysis and synthesis

Understanding these patterns helps match people to jobs that fit their cognitive strengths and identifies areas where training or accommodation might be beneficial.

Specific Cognitive Abilities: Tailoring to Job Requirements

While general intelligence matters across most jobs, specific cognitive abilities become crucial for particular roles. Specific Cognitive Ability Tests (CATs) predict whether an individual will do well in a job given particular cognitive strengths:

Mechanical Ability involves comprehension of mechanical relations and is assessed through tests like the Bennett Mechanical Comprehension Test and SRA Test of Mechanical Concepts. These tests predict success for:

- Train drivers and pilots who must understand vehicle systems

- Engineers who work with mechanical designs

- Emergency services personnel who operate complex equipment

- Factory workers who maintain and troubleshoot machinery

Mechanical ability tests typically show validity coefficients in the .40 to .50 range, explaining 16-25% of variance in job performance for mechanically-oriented positions.

Spatial Ability involves understanding spatial relations and is measured through tests like the Space Relations Test. This ability is crucial for:

- Mechanics who must visualize how parts fit together

- Architects who design three-dimensional structures

- Surgeons who navigate complex anatomical relationships

- Air traffic controllers who track aircraft in three-dimensional space

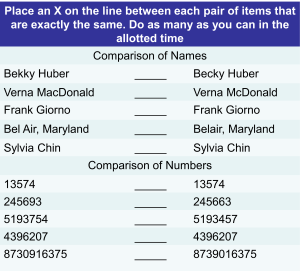

Clerical Ability is relevant for hundreds of jobs including secretary, administrative assistant, and clerk positions, typically measured through tests like the Minnesota Clerical Test. These assessments evaluate:

- Attention to detail in processing information

- Accuracy in routine tasks

- Speed of perceptual processing

- Following detailed procedures consistently

All specific cognitive ability tests show validity coefficients in the .40 to .50 range, but their effectiveness depends entirely on matching the specific ability to actual job requirements identified through job analysis.

Psychomotor Tests: Mind-Body Coordination

Psychomotor tests measure sensory abilities — the speed and accuracy of motor and sensory coordination. These become crucial for jobs requiring precise physical movements or excellent sensory discrimination:

Jobs where psychomotor abilities matter include:

- Packers, machine operators, assemblers, electricians who need manual dexterity

- Fighter pilots, air traffic controllers who require rapid, precise responses

- Baseball players and other athletes who depend on hand-eye coordination

- Surgeons who perform delicate procedures requiring steady hands

Common psychomotor tests include:

- Purdue Pegboard Test: Measures manual dexterity and finger coordination

- Minnesota Manual Dexterity Test: Assesses gross motor coordination

- Hearing and vision tests: Ensure adequate sensory capabilities

These tests typically show validity coefficients in the .40 to .50 range (explaining 16-25% of performance variance), but validities differ significantly as a function of the specific job requirements. This brings us back to the fundamental importance of job analysis in identifying which abilities matter for particular positions.

Personality Testing: The Comeback Story

From Skepticism to Acceptance

Personality testing has had a rocky history in I/O psychology. As early as the 1930s, personality tests were being used to identify who was most likely to become assertive union members, “thugs,” or “agitators.” For decades afterward, researchers dismissed personality tests as ineffective because they showed weak relationships with job performance.

The problem wasn’t that personality doesn’t matter — it was that researchers were using inappropriate personality frameworks and failing to match personality traits to relevant job requirements. Job analyses often reveal important components that include statements such as “being a team player,” which clearly represents an aspect of personality that traditional approaches failed to capture systematically.

The breakthrough came with the Big Five personality model, which organizes personality into five major dimensions: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (OCEAN). This framework provided a common language for personality research and revealed much stronger relationships with job performance.

Personality tests measure individual traits and predispositions to behave in particular ways across situations. For example, people who are “outgoing” tend to be friendly to strangers across various contexts. Popular personality inventories include the 16PF, NEO, Hogan Personality Inventory, and MMPI.

The Big Five and Job Performance

Recent research has found personality tests to be valid predictors of job performance that add variance beyond cognitive aptitude tests, with correlations typically ranging from .20 to .30. Some argue this is an underestimate because researchers often use general personality dimensions to predict specific behaviors rather than matching personality facets to specific job requirements.

Conscientiousness emerged as the superstar — it predicts performance across virtually all jobs because conscientious people work harder, follow through on commitments, maintain higher standards, and persist in the face of obstacles. Conscientiousness consistently shows the strongest relationships with job performance across different occupations.

Extraversion predicts success in sales and leadership roles where interpersonal interaction and influence are crucial. Extraverted individuals tend to be more comfortable with social interaction, more assertive in pursuing goals, and more energized by group activities.

Emotional stability (low neuroticism) matters for high-stress jobs where remaining calm under pressure is essential. Emotionally stable individuals handle stress better, maintain consistent performance under pressure, and are less likely to experience burnout.

Openness to experience relates to creativity, adaptability, and learning orientation — important for jobs requiring innovation or adaptation to change.

Agreeableness can be beneficial for teamwork and customer service roles but may be less important or even counterproductive for positions requiring tough decision-making or negotiation.

The Faking Problem: When Good Intentions Go Wrong

Personality testing faces a fundamental challenge — people can fake their responses if they know the “right” answers. Motivation to fake is influenced by demographic characteristics, individual differences, and perceptual variables related to the selection situation.

Research shows that about one-third to one-half of job applicants engage in some degree of faking, and “fakers” tend to engage in more counterproductive behavior than non-fakers once hired. This creates significant debate about the effect of faking on validity coefficients.

Some researchers argue that faking reduces the validity of personality measures for selection by 25% and that selection decisions are seriously affected because faking substantially changes the rank order of candidates, potentially leading to hiring the wrong people.

However, other research provides a different perspective. One study (Hogan, Barrett, & Hogan, 2007) showed that rejected applicants’ scores on personality measures did not improve when they reapplied for jobs six months later. The researchers reasoned that not being hired the first time would result in motivation to score higher on the personality test the second time around, but this didn’t happen.

This suggests that either people can’t fake as effectively as critics assume, or that those who do fake successfully might actually possess some of the characteristics they’re claiming to have. The debate continues, but most organizations use personality tests anyway because they provide valuable information that can’t be obtained through other methods, especially when combined with other predictors in a comprehensive selection system.

Problems with personality tests extend beyond faking concerns. Noncognitive tests can raise legal issues, particularly when using instruments like the MMPI that were normed on clinical populations rather than normal working adults. Organizations must ensure that personality requirements are clearly job-related and don’t discriminate against protected groups.

Occupational Interests: Finding the Right Fit

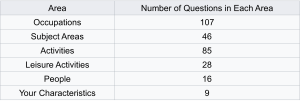

The Strong Interest Inventory represents a sophisticated approach to matching people with careers based on interest patterns. Using Holland’s Model of Occupational Interests, this assessment asks individuals to indicate whether they like or dislike 325 items such as bargaining, repairing electrical wiring, and taking responsibility.

The answers to these questions provide a profile that shows how similar a person is to people already employed in 89 occupations that have been classified into 23 basic interest scales and 6 general occupational themes. The theory behind these tests is elegant: an individual with interests similar to those of people in a particular field will more likely be satisfied in that field than in a field composed of people whose interests are dissimilar.

The six Holland occupational themes are:

- Realistic: Prefer concrete, physical activities and working with tools or machines

- Investigative: Enjoy abstract thinking, research, and scientific problem-solving

- Artistic: Value creativity, self-expression, and aesthetic experiences

- Social: Motivated by helping others and interpersonal interaction

- Enterprising: Drawn to leadership, persuasion, and business activities

- Conventional: Prefer structured environments with clear rules and procedures

Interest inventories don’t predict job performance as strongly as cognitive ability or personality measures, but they’re excellent predictors of job satisfaction, persistence, and career choice. People whose interests align with their work environment tend to be more engaged, stay longer, and experience greater career satisfaction.

Work Values: What Really Matters

Work values represent what people find meaningful and motivating about work. Lofquist and Dawes (1984) found that people are most adjusted to their work and are both satisfied and perform better when important values are met. For example, if employees place high value on good companionship but are placed in a cutthroat competitive environment, it creates a poor fit that affects both satisfaction and performance.

Important work values include:

- Achievement: Ability utilization, accomplishment, recognition for good work

- Independence: Creativity, responsibility, autonomy in decision-making

- Recognition: Advancement opportunities, authority, social status

- Relationships: Quality co-workers, ethical treatment, supportive supervision

- Support: Fair company policies, human relations emphasis, job security

- Work conditions: Adequate compensation, physical comfort, reasonable security

Understanding work values becomes particularly important in our politically charged world. Imagine the implications of being a liberal in a conservative workplace, or vice versa. Value mismatches can create significant stress and performance problems even when people have the necessary skills and abilities for their jobs.

Prior Experience: The Double-Edged Sword

The relationship between experience and performance is more complex than it might initially appear. While there’s generally a positive correlation between experience and job performance, the relationship depends heavily on the quality and relevance of that experience.

People with more experience don’t automatically perform better if it wasn’t high-quality experience that developed relevant skills. In rapidly changing fields, extensive experience can even create negative transfer if people become locked into outdated approaches and resist new methods.

However, knowledge of the field often serves as a better predictor than experience per se. Someone with five years of progressively challenging, well-supervised experience that developed deep understanding will likely outperform someone with ten years of routine, repetitive experience that didn’t build expertise.

The key is distinguishing between experience that builds expertise and experience that simply represents time served. Job analysis helps identify what types of experience actually contribute to performance and what kinds might be less relevant or even counterproductive.

Work Samples: The Ultimate in Face Validity

Work samples represent the most direct approach to prediction — have people perform tasks that directly resemble the actual job. Previous predictors often didn’t closely resemble actual job activities, requiring us to infer relationships between test performance and job performance.

Work samples attempt to duplicate performance criteria and use them as predictors. They develop smaller, standardized tests of actual criterion-related behavior — essentially creating replicas of important job tasks. Examples include:

- Driving tests for positions requiring vehicle operation

- Teaching demonstrations for educational positions

- Coding challenges for software development roles

- Customer service simulations for service positions

Work samples aren’t predictors in the traditional sense — they’re more like imitations of the criterion. This direct relationship explains why work samples have demonstrated validities in the .50 range, making them among the most effective predictors available when they can be developed and administered practically.

The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior in similar situations. When job candidates interviewed at universities, they often had to perform teaching demonstrations, allowing the hiring committee to directly observe teaching skills rather than inferring them from other measures.

However, work samples have significant practical limitations:

- Time-intensive to develop realistic simulations

- Expensive to administer individually

- Limited applicability when job tasks can’t be simulated

- Difficult to standardize across different testing conditions

Work samples are most valuable when jobs involve concrete, observable skills that can be realistically simulated in testing situations. They’re less feasible for jobs involving long-term strategic thinking, relationship building, or other activities that unfold over extended periods.

Media Attributions

- Blue Plaque © Robert Wade is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

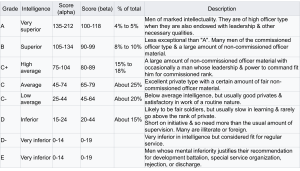

- Army Alpha/Beta Scoring

- WAIS and its Subscales © Alecmconroy is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Carroll’s Three-Strata Model © Tim Bates is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Factor Analysis Matrix

- Clerical Ability Test

- Pegboard Test © Purdue University is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Strong Interest Inventory