4-4: Predictors Where Uncertainty Surrounds the Constructs

Interviews: Popular but Problematic

Interviews: Popular but Problematic

Why Everyone Uses Interviews Despite Their Limitations

Interviews are among the most popular selection devices across all job levels, used by 80-90% of organizations despite research showing they’re not particularly valid in unstructured formats (Huffcutt & Arthur, 1994). This paradox raises an important question: why do organizations continue using a method that research suggests is relatively ineffective?

The answer lies in understanding that interviews serve multiple purposes beyond prediction:

- Realistic Job Preview: They provide candidates with information about the job and organization

- Two-way evaluation: They allow both parties to assess mutual fit

- Manager confidence: Hiring managers believe they can “tell” whether someone will work out

- Human element: They add personal judgment to what might otherwise be purely statistical decisions

- Relationship building: They begin the process of integrating new employees into the organization

The rationale is that the person conducting an interview can gather information that will allow the organization to make accurate predictions about job performance. However, research reveals significant limitations with traditional interview approaches.

Unstructured Interviews: The Problem

Unstructured interviews are constructed without thought to consistency in questioning. Interviewers can ask any question in any order, following their intuition about what might be important or interesting. While this flexibility might seem advantageous, it creates serious problems:

Interviewer bias becomes a major concern when different candidates receive different questions and evaluation criteria. Common biases include:

- First impressions that disproportionately influence final decisions

- “Best applicant is one with a firm handshake” stereotype thinking

- Physical attractiveness giving candidates unfair advantages

- Similar-to-me bias where interviewers favor candidates who remind them of themselves

- Confirmation bias where interviewers seek information that confirms initial impressions

These biases result in fairly low validity for unstructured interviews, with correlations around .20 with job performance (Huffcutt & Arthur, 1994). This means unstructured interviews explain only about 4% of the variance in job performance — barely better than chance.

Structured Interviews: The Solution

Structured interviews consist of a series of job analysis-based questions that are asked of all job candidates in the same way and scored using the same standardized criteria. This approach increases the reliability of the process and enables fairer comparison of applicants across different interviewers and interview sessions.

The structured approach dramatically improves validity, with correlations around .57 with job performance (Huffcutt & Arthur, 1994). This represents more than an eight-fold improvement in explained variance compared to unstructured interviews.

Structured Interview Formats

Situational interviews focus on future behavior by asking interviewees how they would handle work dilemmas or situations. For example: “Assume that a customer gets angry, yells at you, and accuses you of not caring about her needs. You are approaching the end of your shift. What would you do?”

Applicants who describe responses similar to those used by current good employees receive higher ratings. This approach assesses judgment and problem-solving in job-relevant scenarios.

Behavior description interviews focus on past behavior by asking interviewees to describe specific ways they have addressed situations in previous roles. For example: “Think back to a situation in which you were juggling two tasks and realized that you could not finish one without neglecting the other. How did you handle the situation?”

Scoring focuses on resemblance to strategies used by successful current employees. This approach is based on the principle that past behavior is the best predictor of future behavior.

Potential Influences on Interview Effectiveness

Several factors can influence interview validity and fairness:

- Nature of information: Negative information often receives disproportionate weight compared to positive information

- Placement of information: Information presented early in the interview may have greater impact than later information

- Interviewer stereotypes: Preconceived notions about the “ideal candidate” can bias evaluation

- Interviewer job knowledge: Interviewers who understand job requirements make better decisions

- Information combination methods: How interviewers integrate multiple pieces of information affects accuracy

- Nonverbal behavior: Candidate posture, gestures, and other nonverbal cues influence impressions

- Similarity factors: Attitudinal or demographic similarity between candidate and interviewer can create bias

Understanding these influences helps organizations design better interview processes and train interviewers to minimize bias while maximizing the information value of interview interactions.

Biographical Information: Learning from Life History

Biographical information assumes that past behavior is the best predictor of future behavior and can be collected in two primary ways:

Application Blanks are very widely used but often abused because companies fail to get valuable information by using generic, stock surveys purchased from office supply stores. Effective application blanks include anything that has been shown to predict success for the specific job in question (such as relevant education level, specific types of experience, or particular achievements).

However, if taken to court, an employer must be able to defend that items on the application blank are valid predictors of performance. Generic application forms can create legal problems because they often include questions that aren’t job-related and may discriminate against protected groups.

BioData Questionnaires (BIB) tend to be more sophisticated, using multiple-choice items that ask questions about broad areas like family background, hobbies, interests, and life experiences. These questionnaires can include up to 150 items and typically show validity coefficients ranging from .20 to .46.

However, biodata can be risky because many items may not seem obviously job-related to applicants or legal reviewers. Organizations must be able to demonstrate clear relationships between biographical items and job performance to defend their use in selection.

Assessment Centers: Comprehensive Evaluation

Assessment centers use multiple raters to evaluate applicants or incumbents on a standardized set of predictors. Teams of assessors use multiple methods to evaluate performance and potential over typically 2-3 days. More than 50% of major companies use assessment centers, particularly for emergency services and managerial positions.

Assessment centers are only effective if exercises are valid measures of job-relevant characteristics. Combining multiple dimensions and exercises results in overall validity coefficients around .45, making them quite effective but expensive selection methods.

Historical Development

Assessment centers began in Germany in the 1930s and were further developed by the United States during World War II for selecting intelligence and special operations personnel. The comprehensive, multi-method approach proved effective for identifying candidates who could handle complex, high-stakes responsibilities.

The AT&T Management Progress Study

The famous Management Progress Study at AT&T (1956, led by Doug Bray) provided compelling evidence for assessment center validity. Assessment center data was collected on 300 employees between 1956-1960, and these individuals were then tracked for 30 years.

The results were remarkable: assessment center scores correctly identified 94% of those who were unlikely to be promoted, with validity coefficients ranging from .37 to .45 for overall performance criteria. This longitudinal study provided powerful evidence that well-designed assessment centers could predict long-term career success.

Popular Assessment Center Exercises

In-basket exercises require assessees to respond to a series of job-related scenarios as though they are the manager. The assessee is asked to pretend they are suddenly replacing a manager and are given access to everything in the manager’s in-basket: memos, letters, and files. They must prepare statements for the board of directors outlining their plans.

This exercise reveals how people prioritize tasks, organize information, communicate decisions, and handle the realistic time pressures and competing demands that managers face. Assessors can observe problem-solving approaches, decision-making quality, and communication effectiveness.

Leaderless group discussions present groups of employees with issues to resolve, designed to tap managerial attributes from interactions in small groups observed by assessors. Participants must work together to reach decisions without designated leaders, revealing natural leadership tendencies, collaboration skills, and how people handle conflict and ambiguity.

These discussions show how people influence others, build consensus, handle disagreement, and contribute to group problem-solving — all crucial managerial capabilities that are difficult to assess through other methods.

Letters of Reference/Recommendation: The Credibility Problem

Letters of reference tend to be problematic for several reasons that limit their usefulness in selection:

Leniency bias: Letters tend to be overwhelmingly positive because applicants choose people they know will write favorable references. Negative information is rare, making it difficult to differentiate between candidates.

Legal concerns: Letter writers are increasingly afraid of being sued for libel if they provide honest negative feedback. This fear leads to generic, uninformative letters that avoid specific details.

Liability issues: Companies have sued other organizations because letters of reference described employees as good performers when the recommending organization knew this wasn’t accurate. This creates legal exposure for organizations providing references.

Privacy concerns: Letter writers can potentially reveal private information about what employees do on their personal time, raising questions about appropriate boundaries.

Negligent hiring concerns: If organizations don’t seek references and an employee later commits a crime, and it’s discovered that the employee had a problematic history, the hiring organization might face negligent hiring claims.

These competing legal pressures have led many organizations to provide only basic employment verification (dates of employment, job title, salary) rather than substantive performance information, reducing the usefulness of reference checks.

Academic Performance: The Early Career Predictor

Grades show some evidence of predicting job performance, but the relationship is complex. Research suggests that GPA and positive letters of recommendation can predict who will be offered a job much more than who will be successful in that job.

To the degree that grades predict job performance, the relationship is strongest for performance early in someone’s career and weakens over time as work experience becomes more relevant than academic achievement.

GPA is predictive because achieving high grades requires several characteristics that transfer to work performance:

- Motivation to persist through challenging tasks

- Conscientiousness in completing assignments thoroughly and on time

- Knowledge acquisition and retention capabilities

- Cognitive ability to understand and apply complex information

However, the academic environment differs significantly from work environments, and some of the behaviors that lead to academic success (like individual achievement and rule-following) may be less important in collaborative, innovative work settings.

Emotional Intelligence: Promising but Controversial

Emotional Intelligence (EI) refers to the ability of individuals to generate, recognize, express, understand, and evaluate their own emotions and those of others. Proponents argue this leads to effectiveness in the workplace and in personal life, making EI an important predictor of work performance.

Research shows significant correlations between EI and task performance (r = .47), suggesting that emotional capabilities matter for job success beyond traditional cognitive abilities. EI may be a better predictor of peer social interactions than cognitive ability, highlighting its importance for teamwork and leadership.

However, EI faces several challenges as a selection predictor:

- Construct validity concerns: Questions remain about whether EI represents a distinct ability or combinations of personality traits and cognitive skills

- Measurement issues: Different EI measures often don’t correlate highly with each other

- Fad concerns: Some researchers worry EI may be a temporary trend rather than an enduring predictor

- Motivation requirements: High EI alone isn’t sufficient — individuals must also be motivated to use their emotional capabilities

Despite these concerns, EI continues generating research interest because emotional capabilities clearly matter for many jobs, particularly those involving leadership, teamwork, customer service, and other interpersonal demands.

Situational Judgment Tests: Practical Wisdom

Situational Judgment Tests (SJTs) present scenarios that tap applicant judgment in work settings by asking “How would you handle a situation in which…” and providing multiple response options. SJTs have been used since the 1920s but have gained renewed popularity because they show incremental validity over personality tests, job experience, and cognitive ability tests.

SJTs are related to both task and contextual performance, with validity coefficients around .34 for job performance (Christian, Edwards, & Bradley, 2010). Meta-analytic research reveals several important findings:

- Content matters: SJTs measuring teamwork skills and leadership had stronger validities for predicting job performance than those measuring other characteristics

- Format effects: Video-based SJTs showed stronger validities than paper-and-pencil versions, possibly because video better captures the complexity of real work situations

- Job analysis importance: SJTs developed based on systematic job analysis were more valid (r = .38) than those not based on job analysis (r = .29) (McDaniel et al., 2001)

SJTs work because they assess practical judgment — the ability to navigate complex, ambiguous situations where there might not be clearly “right” answers but some responses are clearly better than others. This type of judgment is crucial for many jobs but difficult to assess through traditional testing methods.

Integrity Tests: Predicting Counterproductive Behavior

Integrity tests attempt to predict whether employees will engage in counterproductive or dishonest behaviors like stealing, sabotage, or other forms of workplace deviance. These tests come in two primary types:

Overt integrity tests directly measure attitudes toward theft as well as self-reports of actual theft behaviors. They include questions like:

- “Have you stolen anything from a previous employer?”

- “Is lying ever acceptable?”

- “How much theft occurs in most workplaces?”

Personality-type integrity tests measure personality characteristics like risk-taking, dishonesty, and emotional instability that are associated with counterproductive behaviors. These tests are more subtle and don’t directly ask about theft or dishonesty.

Both types appear valid for predicting counterproductive behaviors (r = .47) and general job performance (r = .34). The validity for predicting counterproductive behavior is particularly impressive and represents one of the strongest relationships found in personnel selection research.

However, integrity tests raise ethical and legal concerns about privacy, the appropriateness of asking about personal beliefs and behaviors, and potential adverse impact on certain groups. Organizations must balance the benefits of identifying potentially problematic employees against concerns about fair treatment and privacy rights.

Contemporary and Controversial Methods

Polygraph Testing

The polygraph is permitted only in certain job sectors but is generally not very useful even where allowed (such as screening for national security positions). Research showing the lack of validity is substantial and compelling, leading to the Employee Polygraph Protection Act of 1988, which prohibited polygraph use for most private sector jobs.

Despite these limitations, research with 600 white-collar workers (300 in prison for white-collar crimes, 300 not incarcerated) revealed clear differences in responding that reflected “social conscientiousness.” Those in prison showed greater tendencies toward irresponsibility and disregard for rules and social norms, suggesting that personality-based approaches might be more effective than physiological measures.

Credit Rating

While potential employers don’t have access to credit scores, they might request modified credit reports for insight into credit history. Credit checks can:

- Verify identity and confirm employment history

- Provide insights into responsibility and financial management

- Reveal potential conflicts of interest or vulnerability to financial pressure

However, employers must obtain written consent to access credit reports, and poor credit can result from circumstances beyond individual control (medical emergencies, economic downturns, identity theft), raising questions about fairness and job-relatedness.

Drug and Alcohol Testing

Drug screening has become common for new hires, though false positives remain a concern. Research provides evidence for the validity of drug testing: Normand, Salyards, and Mahoney (1990) reported that 5,500 postal service applicants were given drug tests, and after 15 months, employees who had tested positive at hire had absenteeism rates almost 60% higher than those who tested negative. Additionally, almost 50% more employees who had tested positive were terminated during the 15 months (many for excessive absenteeism).

Organizations face legal issues whether they screen employees or not — potential liability for accidents caused by impaired employees if they don’t test, but privacy concerns and potential discrimination claims if they do test without clear job-relatedness.

Social Media Screening

As many as 70% of employers examine candidates’ social media during the hiring process. This publicly available information is free and can reveal information about judgment, professionalism, and character that might not emerge through other selection methods.

Research shows that 57% of HR professionals have reported denying someone a job based on inappropriate social media content. However, research on validity is still limited, and questions remain about fairness, privacy, and job-relatedness of social media information.

Some employers use informal behavioral observations during the hiring process, such as:

- Taking candidates to lunch and observing their treatment of restaurant staff

- Observing whether candidates push in their chairs when leaving

- Using the “salt test” — noting whether candidates add salt to food before tasting it (though the rationale for this particular test remains unclear)

Graphology: The Persistence of Pseudoscience

Graphology (handwriting analysis) operates on the theory that the way people write reveals their personality, which should indicate work performance. Although graphology is used more often in Europe than in the United States, European employees react as poorly to it as their American counterparts.

Graphologists analyze the size, slant, width, regularity, and pressure of writing samples to infer information about temperament and mental, social, work, and moral traits. However, research consistently shows that graphology lacks validity for employment purposes.

Interestingly, graphology predicts best when the writing sample is autobiographical (the writer composes an essay about themselves), which means graphologists are likely making predictions based on the content of the writing rather than the characteristics of the handwriting itself.

The Future of Prediction

The field of personnel selection continues evolving rapidly as new technologies and research methods emerge. Several trends are likely to shape future developments:

Technology Integration: AI-driven assessments, virtual reality simulations, and sophisticated data analytics are creating new possibilities for assessing human potential while raising new questions about fairness, privacy, and transparency.

Legal and Ethical Evolution: As selection methods become more sophisticated, legal and ethical frameworks must evolve to balance organizational needs with individual rights and societal values.

Personalization: Future selection systems may become more personalized, adapting to individual candidates while maintaining standardization and fairness across all applicants.

Continuous Assessment: Rather than one-time selection decisions, organizations may move toward continuous assessment and development models that recognize human potential as dynamic rather than fixed.

The fundamental challenge remains the same — understanding and predicting human performance in complex organizational environments. As work continues changing, our methods for selecting people must evolve while maintaining scientific rigor and ethical standards that respect human dignity and promote fair treatment for all candidates.

The fundamental challenge remains the same — understanding and predicting human performance in complex organizational environments. As work continues changing, our methods for selecting people must evolve while maintaining scientific rigor and ethical standards that respect human dignity and promote fair treatment for all candidates.

Media Attributions

- Uncertainty & Doubt © GDJ is licensed under a Public Domain license

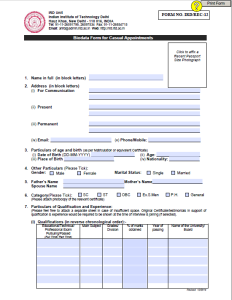

- Application Form

- EEOC Seal © U.S. Government is licensed under a Public Domain license