5-4: Legal Issues in Selection

Personnel selection operates within a complex web of laws designed to prevent discrimination and ensure fair employment opportunities. Understanding these requirements isn’t just about avoiding lawsuits — it’s about creating selection systems that are both effective and fair to everyone.

Personnel selection operates within a complex web of laws designed to prevent discrimination and ensure fair employment opportunities. Understanding these requirements isn’t just about avoiding lawsuits — it’s about creating selection systems that are both effective and fair to everyone.

Here’s something that might surprise you: prior to the 1960s, it was completely legal to discriminate in hiring employees. That seems unthinkable now, but employment discrimination was perfectly acceptable under the law. Before we dive into the current legal landscape, it’s worth noting that we still operate under employment at-will in most situations — a common law doctrine stating that employers and employees can initiate and terminate employment relationships at any time, for any or no reason at all. However, due to recent cases about “wrongful discharge,” many companies have adopted “just cause” discharge policies, and specific contracts can override employment at-will arrangements.

Federal Legislation and Guidelines

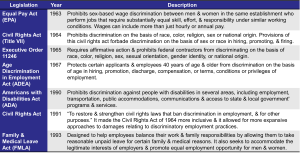

The legal landscape for hiring changed dramatically with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, particularly Title VII, which said “no more” to employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. This legislation also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) in 1965 to enforce these laws and investigate discrimination complaints.

The Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures (1978) got more specific about what constitutes legally defensible selection practices. These guidelines introduced the concept of adverse impact, which they defined using the “80% rule” — basically, if any protected group’s selection rate is less than 80% of the highest-performing group’s rate, you might have a problem on your hands. In 1987, SIOP published its “Principles for the Validation and Use of Selection Procedures” (revised in 2018), which serves as a how-to guide for hiring under the Guidelines.

Additional laws expanded these protections: the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (1967) protects workers 40 and older, the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) prohibits disability discrimination, the Civil Rights Act of 1991 expanded damages and clarified employer obligations, the Family and Medical Leave Act (1993) provides job-protected leave for family-related issues, and the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act (2009) extended the time frame for filing pay discrimination lawsuits.

Understanding Discrimination Cases

When someone files a discrimination lawsuit, there’s a specific process that unfolds. First, the plaintiff must demonstrate a “prima facie case” — basically, the numbers on their face indicate adverse impact exists. The defendant can then argue against the statistics by showing the plaintiff is looking at partial data, interpreting it incorrectly, or examining the wrong information entirely.

Adverse Impact and Legal Defenses

When adverse impact occurs, organizations have several options for defending their practices. They can demonstrate that despite the disparate impact, their selection procedures are job-related and valid for predicting success across all groups (this is where validation studies become crucial, and validity generalization studies might be sufficient evidence). They might claim a Bona Fide Occupational Qualification (BFOQ) exists, though courts interpret these very narrowly.

For example, in the famous Diaz v. Pan Am case, Diaz was a male rejected for a flight attendant position. When he demonstrated adverse impact existed, Pan Am claimed that being female was a BFOQ because attendants needed to be nurturing and because passengers preferred female attendants. The court ruled against Pan Am, determining that gender was not a BFOQ because the primary role of flight attendants is safety — passenger comfort was considered a secondary function.

The landmark Griggs v. Duke Power (1971) case established a crucial principle: even without any intent to discriminate, if your selection procedures create adverse impact, you must prove they’re job-related and necessary for business success. This case distinguished between disparate impact (adverse impact without discriminatory intent) and disparate treatment (intentionally treating people differently).

Another important case, Albermarle Paper v. Moody (1975), ruled that items used to validate employment requirements must be job-related.

The Civil Rights Act also prohibits discrimination based on national origin, meaning no one can be denied equal employment because of ancestry, culture, or birthplace. This became particularly relevant after 9/11 with backlash against Muslims. The Act also covers issues like accent discrimination, religious accommodation, and pregnancy discrimination.

Sexual harassment is prohibited under the Civil Rights Act, with courts distinguishing between quid pro quo harassment (“this for that” — like demanding sexual favors for job benefits) and hostile work environment harassment. Landmark cases include Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson (1986), and of course, the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings in 1991 brought these issues into national prominence.

More recently, sexual orientation became a protected class under Title VII through cases like Bostock v. Clayton County (2020), where Bostock was fired after expressing interest in joining a gay softball league, and R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. EEOC (2020), involving Aimee Stephens, who was fired after transitioning from male to female.

Accommodation and Accessibility

The Americans with Disabilities Act requires organizations to make reasonable accommodations for qualified individuals — those who can perform the essential functions of a job. Essential functions are the tasks that are really significant and meaningful to the job — not just busy work or minor duties that could easily be done by someone else.

Reasonable accommodations are changes in job function that allow qualified, disabled individuals to successfully perform their jobs, but only to the extent that such accommodations don’t impose undue hardship with respect to difficulty of implementation or expense. What constitutes undue hardship depends on the size of the company and its access to resources.

Job analysis becomes super important in ADA compliance because it helps define what’s essential versus what’s just nice to have, and it guides decisions about appropriate accommodations. For example, in Etheridge v. State of Alabama (1994), the court determined that if a job involves heavy lifting regularly, then a person with a bad back can be legally excluded because lifting is an essential component. But if a job only occasionally requires some lifting, then a person with a bad back cannot be kept out — the company would be expected to make reasonable accommodations.

The Martin v. PGA Tour cases (1998, 2000) illustrate how complex accommodation decisions can be. Martin had a bad leg and needed to ride a golf cart during tournaments. The question became: is this an unfair advantage or a leveling of the playing field? The court ultimately ruled in Martin’s favor.

It’s worth noting that the ADA was amended in 2009 to expand how individuals are evaluated for disabilities and to broaden the list of major life activities. Some argue for further amendments because many impairments still don’t meet the current definition of disability.

Additional Legal Protections

Beyond the major civil rights legislation, several other laws impact personnel selection:

The Fair Labor Standards Act creates the right to minimum wage and “time-and-a-half” overtime pay for work over 40 hours per week, while prohibiting oppressive child labor.

Executive Order 11246 prohibits federal contractors doing over $10,000 in government business annually from discriminating and requires affirmative action in employment (updated in 2014 to include sexual orientation and gender identity).

Background checking has become increasingly important, with the Fair Credit Reporting Act regulating how organizations can use credit reports and criminal background information in hiring decisions (Burke, 2005). Many states and cities have also enacted “ban the box” legislation that limits when employers can ask about criminal history.

Recent legal developments have further shaped the personnel selection landscape. The Mobley v. Workday case (2024) highlighted concerns about AI bias in hiring algorithms, emphasizing the need for careful oversight of automated selection tools. The Supreme Court’s decision in Murray v. UBS Securities LLC (2024) strengthened whistleblower protections for employees who report misconduct, requiring employers to prove they would have terminated employees regardless of their whistleblowing activities. Additionally, Muldrow v. City of St. Louis (2024) clarified that employees don’t need to show “significant harm” to prevail in Title VII discrimination claims involving job transfers, lowering the bar for such cases.

Contemporary Challenges: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Selection

The landscape of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in personnel selection has undergone dramatic changes in recent years, creating new challenges and uncertainties for organizations seeking to build diverse workforces while maintaining legal compliance.

The 2023 Supreme Court Watershed Moment

The Supreme Court’s decisions in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina (2023) fundamentally altered the legal landscape surrounding race-conscious selection practices. While these cases specifically addressed college admissions, their reasoning has created ripple effects throughout employment law, raising questions about the future of diversity-focused hiring practices.

The Court’s ruling that race-conscious admissions programs violated the Equal Protection Clause has led many organizations to reassess their own diversity recruitment and selection strategies. Legal experts debate whether the decision’s logic extends to private employer diversity initiatives, creating a climate of uncertainty around practices that were previously considered legally sound.

The “Reverse Discrimination” Phenomenon

Following the 2023 Supreme Court decisions, there has been a notable increase in “reverse discrimination” lawsuits challenging diversity programs. The case Ames v. Ohio Department of Youth Services, currently before the Supreme Court, may determine whether majority plaintiffs must meet heightened standards when bringing such claims (HR Morning, 2025). If the Court lowers these standards, employment lawyers predict a significant increase in challenges to diversity-focused hiring practices.

This trend has forced HR departments to walk an increasingly narrow tightrope: How do you promote diversity and inclusion while avoiding legal challenges that claim these efforts discriminate against majority group members?

Practical Implications for Selection Systems

Organizations are responding to this changed legal environment in various ways:

Risk-Averse Approaches: Some companies have eliminated explicit diversity goals and metrics from their hiring processes, focusing instead on “diversity of thought” or socioeconomic diversity that may be less legally vulnerable.

Process-Focused Strategies: Rather than outcome-based diversity goals, many organizations are emphasizing bias-free processes, structured interviews, and objective selection criteria that may naturally lead to more diverse outcomes without explicitly considering race or gender.

Legal Safe Harbors: Companies are increasingly seeking legal guidance on which diversity practices remain defensible, often settling on approaches like expanding recruitment networks, removing bias from job descriptions, and ensuring selection panels are diverse.

The Technology Wild Card

Artificial intelligence and machine learning in selection processes have introduced new complexities to DEI efforts. While these technologies promise to reduce human bias, they can also perpetuate historical discrimination patterns present in training data. The Mobley v. Workday case (2024) exemplifies growing concern about algorithmic bias in hiring tools.

Organizations must now consider whether their AI-driven selection tools comply with both traditional equal employment opportunity requirements and emerging algorithmic fairness standards. Some jurisdictions are beginning to require “algorithmic auditing” to ensure AI hiring tools don’t produce discriminatory outcomes.

Looking Forward: Navigating Uncertainty

The current legal environment requires organizations to be more strategic and careful about their diversity efforts than ever before. Successful approaches tend to focus on:

- Inclusive processes rather than demographic outcomes

- Bias elimination rather than preferential treatment

- Expanded recruitment rather than differential selection criteria

- Data-driven approaches that can demonstrate job-relatedness and business necessity

This evolving landscape means that what was legally acceptable yesterday might be challenged tomorrow. Organizations must stay agile, continuously monitoring legal developments while maintaining their commitment to building diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces within whatever boundaries the law establishes.

The fundamental tension remains: How do you achieve diversity goals in a legal environment that increasingly restricts explicit consideration of demographic characteristics? The answer may lie in addressing systemic barriers and bias at every stage of the selection process while maintaining strict adherence to job-related, legally defensible criteria.

Cutting-Edge Innovations in Legal Compliance

Modern HR practices are increasingly integrating advanced technologies to enhance personnel selection processes while maintaining legal compliance. These innovations offer strategic advantages but also present implementation challenges that organizations must navigate carefully.

AI-Enhanced Decision Support: Artificial Intelligence systems are now being used to assist hiring managers by analyzing large volumes of candidate data and identifying patterns that predict job success. These systems can evaluate resumes, assess video interviews, and even simulate job scenarios to provide recommendations. While AI can improve efficiency and consistency, it requires careful oversight to avoid perpetuating biases present in historical data.

Predictive Analytics Dashboards: Organizations are deploying dashboards that visualize key metrics related to candidate performance, turnover risk, and cultural fit. These dashboards aggregate data from multiple sources, including assessments, past hiring outcomes, and employee engagement surveys. By providing real-time insights, they enable data-driven decision-making and strategic workforce planning.

Ethical Auditing of Selection Algorithms: As algorithmic decision-making becomes more prevalent, ethical auditing has emerged as a critical practice. Audits evaluate whether selection algorithms are fair, transparent, and compliant with legal standards. This includes testing for disparate impact, ensuring explainability of decisions, and documenting the sources and limitations of training data. Ethical auditing helps build trust in automated systems and protects organizations from legal and reputational risks.

Strategic Value and Implementation Challenges: These innovations can significantly enhance the accuracy, fairness, and scalability of selection processes. However, successful implementation requires cross-functional collaboration between HR, data science, and legal teams. Challenges include data privacy concerns, integration with existing HR systems, and ensuring user adoption among hiring managers. Organizations must also stay informed about evolving regulations and best practices to maintain ethical and effective use of technology in selection.

Conclusion

Personnel selection represents one of the most critical functions any organization performs. It significantly impacts productivity, employee satisfaction, and overall success. Effective selection requires a systematic approach grounded in solid job analysis, validated assessment methods, and legal compliance, while balancing multiple considerations including validity, utility, cost-effectiveness, and fairness.

The research evidence overwhelmingly supports structured, validated selection procedures over informal or unstructured approaches. While challenges such as adverse impact and cost considerations require careful attention, organizations that implement evidence-based selection practices gain substantial competitive advantages through improved employee performance and reduced turnover.

Future developments in personnel selection will likely continue emphasizing technological integration, fairness and inclusion, and identification of emerging predictors of job success in our rapidly evolving work environments. Success in personnel selection requires ongoing attention to research developments, legal requirements, and organizational needs while maintaining focus on the fundamental goal: identifying candidates who will contribute effectively to organizational success.

Whether you’re preparing for your own job search, planning a career in HR, or aspiring to management roles where you’ll make hiring decisions, understanding the science of personnel selection will serve you incredibly well. In today’s competitive environment, the organizations that consistently hire the best people are the ones that thrive — and now you understand the science behind how they do it. Pretty cool, right?

Media Attributions

- Lady Justice © Lucy Skywalker is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Major US Employment Laws © Jay Brown

- Seal of the Office of Personnel Management © U.S. Government is licensed under a Public Domain license

- President Obama Signs the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 © Joyce Bogoshian is licensed under a Public Domain license