6-1: Job Performance

Have you ever wondered how companies actually figure out if they’re hiring the right people? Or why some performance reviews seem fair while others feel completely off the mark? You’re about to dive into one of the most crucial—and challenging—aspects of workplace psychology.

Have you ever wondered how companies actually figure out if they’re hiring the right people? Or why some performance reviews seem fair while others feel completely off the mark? You’re about to dive into one of the most crucial—and challenging—aspects of workplace psychology.

Think about it this way: imagine you’re trying to predict who’ll be the best basketball player. You might look at their height, shooting percentage, or speed (these are called predictors). But how do you actually measure “being a good basketball player”? Do you count points scored? Assists? Team wins? How players get along with teammates? This is exactly the challenge organizations face when trying to measure job performance.

The scientific foundation of personnel selection rests on the fundamental relationship between predictors and criteria. While predictors represent the assessment tools and procedures used to evaluate job candidates, criteria serve as the evaluative standards that define success or failure in organizational contexts. Remember linear regression from your statistics class? We measure a predictor and use it to predict a criterion. For example, SAT scores (predictor) predict college GPA (criterion). Predictors are inputs; criteria are outcomes.

A criterion represents an evaluative standard that functions as a measuring instrument for assessing employees’ or organizations’ success or failure. In the linear regression framework that underlies personnel selection, predictors serve as input variables used to forecast criterion outcomes. This predictor-criterion relationship forms the empirical foundation for validating selection systems and making evidence-based hiring decisions.

You might be thinking, “Why does this matter to me?” Well, whether you’re applying for jobs, managing people, or running a business, understanding how performance is measured affects everything from who gets hired to who gets promoted to how fair workplace decisions really are.

The importance of criteria in industrial psychology can’t be overstated. They reflect organizational and individual performance outcomes that directly impact competitive advantage and profitability. Organizations use criteria for multiple purposes: appraising individual employee performance, validating selection batteries to ensure assessment accuracy, making layoff decisions during organizational restructuring, and evaluating the effectiveness of training programs and other interventions. In a competitive market, companies are driven by performance and profits, making criterion selection absolutely critical.

Here’s where it gets tricky: measuring job performance represents perhaps the most complex challenge in criterion development. It’s like trying to capture everything that makes someone good at their job while keeping it practical enough for managers to actually use. This complexity requires sophisticated theoretical frameworks and measurement approaches that can adequately represent the true nature of workplace performance while maintaining practical utility for organizational decision-making.

Job Performance as a Criterion

Let’s start with a fundamental question: what exactly is job performance? Job performance represents a hypothetical construct intended to reflect how well individuals perform their assigned work roles. Just like intelligence or personality, you can’t directly see job performance—you have to infer it through various ways of measuring and defining it.

The challenge lies in developing operational definitions that adequately capture the essential elements of performance while remaining practically feasible for organizational implementation. It’s like trying to define what makes a good friend—you know it when you see it, but putting it into measurable terms is surprisingly difficult.

Traditional approaches to operationally defining job performance have employed various metrics including time required to complete training courses, number of products manufactured, total days absent from work, total sales revenue generated, and promotion rates within organizations. While these measures provide concrete, quantifiable indicators of certain aspects of performance, each suffers from significant limitations that illustrate just how complex performance measurement really is.

Let’s look at some examples that might surprise you. Consider the apparent simplicity of measuring time to complete a training course as an indicator of learning ability and job readiness. Seems straightforward, right? But this measure becomes problematic when workers have varying amounts of time available to dedicate to training due to competing job responsibilities. The person who takes longer might actually be juggling more urgent work tasks, not learning more slowly.

Similarly, counting the number of pieces produced seems like an objective performance measure, but production output depends heavily on technology quality, equipment availability, and workflow efficiency—factors largely beyond individual worker control. You might be the hardest worker on the floor, but if your machine keeps breaking down, your numbers won’t reflect your effort.

Absence measures face the challenge of distinguishing between excused and unexcused absences. Treating medical leave and voluntary absenteeism the same way fails to capture meaningful performance differences. Sales revenue figures must account for territory differences, product pricing strategies, competitive market conditions, and promotional campaigns that influence results independent of individual salesperson effectiveness. And promotion rates? They often reflect organizational turnover patterns and position availability rather than purely individual merit.

These examples illustrate the fundamental challenge in job performance measurement: separating individual contributions from situational and organizational factors that influence observable outcomes. This challenge has led to more sophisticated theoretical approaches that attempt to distinguish between what individuals do (their behaviors) and what results from those behaviors (outcomes influenced by multiple factors).

Campbell’s Model of Job Performance

This is where Campbell’s influential model comes in to save the day by providing crucial distinctions that clarify the conceptual foundation of performance measurement (Campbell, 1990). Think of Campbell as the person who finally organized the messy closet of performance measurement theory.

Performance refers specifically to actions or behaviors that individuals exhibit that are relevant to organizational goals (think: making money for the company). This behavioral focus emphasizes what people actually do in their work roles rather than the results that may or may not follow from those behaviors. It’s the difference between how well you play the game versus whether your team wins.

Effectiveness represents the evaluation of performance results, recognizing that outcomes often depend on forces beyond individual worker control. An individual may demonstrate excellent performance behaviors but achieve poor effectiveness due to equipment failures, market conditions, or organizational constraints. Conversely, someone may achieve high effectiveness despite mediocre performance due to favorable circumstances or exceptional resources.

Productivity captures the relationship between effectiveness and efficiency by calculating the ratio of output achieved to the cost of achieving that level of output. Think of it this way: productivity equals effectiveness divided by cost. This economic perspective becomes particularly important for organizational decision-making, as it considers both the magnitude of results and the resources required to achieve them.

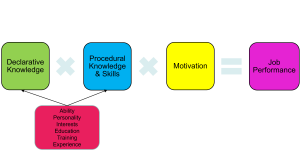

Campbell’s model also distinguishes between declarative knowledge (information known about how to accomplish tasks) and procedural knowledge (knowing how to actually perform tasks). This distinction proves critical for understanding performance development. You might know everything about driving a car from reading the manual (declarative knowledge), but that doesn’t mean you can actually drive well (procedural knowledge).

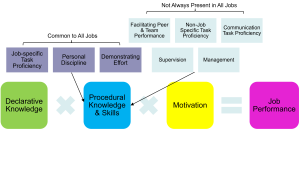

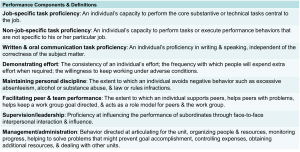

The full Campbell model identifies eight specific performance components that represent behaviorally-oriented dimensions applicable across diverse job contexts. These components include job-specific task proficiency, non-job-specific task proficiency, written and oral communication proficiency, demonstrating effort, maintaining personal discipline, facilitating peer and team performance, supervision and leadership, and management and administration.

This comprehensive framework recognizes that job performance extends beyond narrow technical task execution to include broader behavioral contributions that support organizational effectiveness. The model’s emphasis on behaviors rather than outcomes provides a more defensible foundation for performance evaluation and development, as it focuses on factors within individual control rather than results influenced by external circumstances.

Typical Versus Maximum Performance

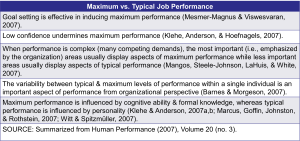

Here’s something that might blow your mind: there’s a huge difference between what you can do and what you normally do at work. Typical performance represents what individuals normally do under regular work conditions, while maximum performance represents what individuals can achieve when fully motivated and focused.

Research suggests that typical performance levels often hover around 70% of maximum capability. Think about it—when was the last time you gave 100% effort all day, every day? It’s probably not sustainable, and that’s exactly the point.

Obviously, employers want 100% effort, but how long can a worker realistically give 100% effort? Understanding this distinction proves essential for selection system design and performance evaluation. While organizations naturally desire maximum performance from all employees, the sustainability of peak effort represents a fundamental limitation. Hermann Ebbinghaus’s classic research on distributed versus massed practice demonstrates that peak performance can be maintained for relatively short periods, but attempts to sustain maximum effort over extended timeframes typically result in performance decrements and potential burnout. Presumably, we’re able to come closer to maximum performance for shorter time periods.

The typical-maximum performance distinction also influences the validity of selection procedures depending on when and how performance criteria are measured. Selection systems validated against maximum performance measures may not accurately predict typical job performance, while systems based on typical performance may underestimate candidates’ true capabilities.

Organizations must carefully consider whether their performance criteria capture typical or maximum performance and align their expectations accordingly. Job demands that require sustained high performance may benefit from different selection approaches than positions where periodic peak performance proves more important than consistent moderate performance.

Comprehensive Theories of Job Performance

You might be wondering, “Are there any theories that actually capture everything about job performance?” Contemporary performance theory has evolved toward more comprehensive models that encompass the full range of workplace behaviors that contribute to organizational effectiveness.

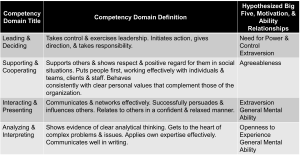

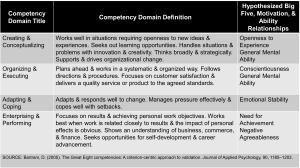

Bartram’s “Great Eight” model represents a significant advancement in performance theory by providing a framework intended to explain performance across diverse cultural and occupational contexts (Bartram, 2005). This broad model is intended to explain a very broad definition of job performance, including things we’ve already discussed as well as Organizational Citizenship Behaviors and Counterproductive Work Behavior.

The Great Eight competencies include: Leading and Deciding, Supporting and Cooperating, Interacting and Presenting, Analyzing and Interpreting, Creating and Conceptualizing, Organizing and Executing, Adapting and Coping, and Enterprising and Performing.

What’s really impressive about this model is that it has demonstrated validity across nine different countries, suggesting that these competencies represent fundamental dimensions of workplace performance that transcend specific cultural or organizational contexts. That’s pretty remarkable when you think about how different work cultures can be around the world. These eight competencies have also been systematically related to personality characteristics and cognitive abilities.

The comprehensiveness of modern performance models reflects recognition that traditional narrow definitions of job performance failed to capture the full range of behaviors that contribute to organizational success. Contemporary work environments require individuals to engage in complex interpersonal interactions, adapt to changing conditions, and contribute to collective goals in ways that extend beyond specific technical task requirements.

These broad performance models also facilitate the integration of personality characteristics and cognitive abilities with performance outcomes. Research demonstrates systematic relationships between specific personality dimensions and different performance competencies, enabling more sophisticated approaches to selection and development that consider the full spectrum of job-relevant characteristics.

Task Versus Contextual Performance

Here’s where things get really interesting. Modern performance theory has completely revolutionized how we think about what contributes to workplace success. We now distinguish between task performance (work-related activities that contribute to the organization’s technical core) and contextual performance (activities that help or hurt the broader organizational, social, and psychological environment) (Borman & Motowidlo, 1997).

Task performance encompasses the formal job requirements and technical activities that directly contribute to organizational production or service delivery. These activities typically appear in job descriptions, performance standards, and formal performance appraisal systems. Task performance varies substantially across different jobs, as each position involves unique technical requirements and responsibilities.

Contextual performance includes behaviors that support the organizational environment within which task performance occurs. These behaviors often resemble “assists” in sports—they may not directly produce organizational output but facilitate others’ effectiveness and contribute to overall organizational success. If task performance is goals scored, then contextual performance is assists.

Several characteristics distinguish task from contextual performance. Task activities vary across jobs, while contextual behaviors are similar across jobs. Task activities are more likely than contextual to be formally instituted as part of job descriptions and performance appraisals. They also have different antecedents.

Research has identified different antecedents for task and contextual performance. Cognitive ability demonstrates stronger relationships with task performance, as technical job requirements typically depend on reasoning, problem-solving, and learning capabilities. Personality factors, particularly conscientiousness, show stronger relationships with contextual performance, as these behaviors depend more on motivation and interpersonal orientation than technical capability.

This distinction has important implications for selection system design. Organizations seeking to improve task performance might emphasize cognitive ability testing, while those concerned with contextual performance might focus more heavily on personality assessment and behavioral interviewing techniques.

Organizational Citizenship Behaviors

You’ve probably seen this at work without even realizing it had a name. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors (OCBs) represent a subset of contextual performance that encompasses voluntary behaviors valued by organizations but not formally required. These are on-the-job behaviors that are valued but not required.

Various researchers have proposed categorical schemes for organizing OCBs, including dimensions such as conscientiousness, altruism, generalized compliance, sportsmanship, civic virtue, and courtesy. However, factor-analytic research suggests that different OCB categories may reflect a single underlying factor rather than distinct behavioral dimensions.

Borman and Motowidlo identified five primary OCB dimensions: working with extra enthusiasm and effort, volunteering for activities not formally part of the job, helping others with their work responsibilities (sportsmanship, organizational courtesy), meeting deadlines and complying with organizational rules and regulations (civic virtue or conscientiousness), and supporting and defending the organization (Borman, Penner, Allen, & Motowidlo, 2001).

But research shows that all OCBs fall into a single factor rather than distinct categories.

Research demonstrates that OCBs identified in U.S. samples apply in international contexts including Belgium, Mexico, Nigeria, China, and Australia, suggesting that these behaviors represent universal aspects of workplace contribution rather than culture-specific phenomena. However, OCB frequency is related to cultural time orientation. China has a long-term time orientation and higher levels of OCBs, while the US has short-term time orientation and lower levels of OCBs.

The organizational context significantly influences when OCBs benefit organizational effectiveness. Hunt (2002) found that in very structured jobs where employees are expected to follow formal and rigid rules for job performance (e.g., steel workers and barge deckhands), OCBs are likely to do as much harm as good. It appears that “initiative” might actually increase the risk of an accident in these highly structured safety environments.

Conversely, jobs high in autonomy are more likely to be associated with the appearance of OCBs. When autonomy is low, conscientious workers may be less likely to display OCBs, perhaps recognizing that such behaviors could interfere with prescribed procedures. Data further support the notion that the work environment can constrain the appearance of OCB.

The organizational political environment also affects OCB occurrence. Research shows that the more negative the political environment (characterized by favoritism, dishonesty, and manipulation), the less likely it is that OCBs will appear. Positive environments that reward merit and support employee development encourage voluntary contributions.

Individuals high in agreeableness tend to display OCBs in both positive and negative environments, suggesting that personality influences OCB propensity independent of situational factors. Research has found evidence for a positive relationship between conscientiousness and OCB.

Bachrach, Powell, Bendoly, and Richey (2006) found that OCB was considered more important when work tasks required collaboration among workers or within work teams.

Group-level research reveals that OCBs contribute to team effectiveness by improving communication and social processes within work groups. Meta-analytic evidence from 38 studies over 10 years demonstrates positive relationships between group-level OCBs and group performance, suggesting that these behaviors benefit both individual and collective effectiveness (Nielsen, Hrivnak, & Shaw, 2009). Group level OCBs improved social processes (communication) within teams.

However, gender bias may affect how OCBs are perceived and rewarded. Research indicates that men engaging in OCB are viewed positively, while women displaying the same behavior are seen as simply doing their jobs (Heilman & Chen, 2005). This bias could reduce motivation for women to engage in voluntary contributions that may not receive appropriate recognition.

Organizations increasingly recognize the importance of OCBs for competitive advantage and are developing selection instruments to predict employees’ likelihood of engaging in these behaviors. Some frameworks propose that OCBs create social capital through favorable coworker relationships that enhance organizational performance and effectiveness.

Counterproductive Work Behaviors

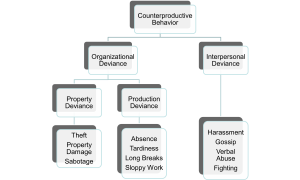

Now let’s talk about the dark side of workplace behavior. Counterproductive Work Behaviors (CWBs) represent the negative side of contextual performance, encompassing behaviors that harm or detract from organizational effectiveness. These behaviors include theft, sabotage, interpersonal abuse, and various withdrawal behaviors that undermine organizational goals.

Research demonstrates several important findings about CWBs. Personality factors are related to CWBs, but the single best predictor of whether an employee will steal is whether they have an opportunity to steal! Counterproductive behaviors are more strongly related to organizational and individual performance than OCBs, suggesting that preventing harmful behaviors may be more important than encouraging helpful ones. Sometimes the same people may exhibit both OCBs and CWBs, indicating that these behaviors may not represent opposite ends of a single continuum. CWBs have strong negative effects on business unit performance and productivity.

Sackett and colleagues have proposed a hierarchical model of counterproductive work behavior that organizes these behaviors into major categories (Sackett, Berry, Wiemann, & Laczo, 2006). At the highest level, the model distinguishes between behaviors directed toward the organization and those directed toward individuals within the organization.

Vardi and Weiner’s framework categorizes counterproductive behaviors based on their intended beneficiaries: S-behaviors done for self-gain (e.g., theft), O-behaviors done for organizational gain (e.g., misstating profit or overbilling) – though O-behavior can also be for self-gain (protect your own position!), and D-behaviors that are purely destructive (e.g., sabotage, assault) (Vardi & Weiner, 1996).

Predicting and Preventing Counterproductive Work Behaviors

You might be wondering, “Can we actually predict who’s going to engage in these harmful behaviors?” James and colleagues propose that workplace aggression stems from flawed rationalization processes where aggressors convince themselves that their behavior is justified (James et al., 2005). This insight led to the development of assessment instruments that measure implicit aggressive tendencies through “reasoning” tasks that appeal differentially to aggressive and non-aggressive individuals.

For example, consider this test item: “The old saying ‘an eye for an eye’ means that if someone hurts you, then you should hurt that person back. If you are hit, then you should hit back. If someone burns your house, then you should burn that person’s house. Which of the following is the biggest problem with the ‘eye for an eye’ plan?”

- a) It tells people to turn the other cheek b) It offers no way to settle a conflict in a friendly manner c) It can only be used at certain times of the year d) People have to wait until they are attacked before they can strike

The hidden aggressive response is “d.” It appeals to aggressive individuals who see this as a problem since they cannot engage in a preemptive strike. Answer “b” is attractive to nonaggressive individuals because it implicitly accepts the notion that compromise and cooperation are more reasonable than conflict.

Laboratory and field studies support the validity of this approach for predicting counterproductive behaviors. Intramural basketball players who scored high on this hidden aggression test committed more egregious fouls and were more inclined to get into fights and to verbally harass other players or officials.

Based on basic research findings, Baron proposed several strategies for preventing counterproductive work behaviors (Baron, 2004):

Punishment that is prompt, certain, strong, and justified can deter future misconduct. However, punishment must be applied consistently and fairly to avoid creating perceptions of injustice that might actually increase counterproductive behaviors.

Quick and genuine apologies to individuals who are unjustly treated can prevent escalation of conflicts and reduce motivation for retaliation. Organizations should establish procedures for addressing grievances promptly and fairly.

Exposure to positive role models including coworkers and supervisors who maintain professional behavior even when provoked can establish norms that discourage counterproductive responses to workplace stressors.

Training in social and communication skills can help individuals who might otherwise interact in provocative ways develop more effective interpersonal approaches. These interventions may be particularly valuable for individuals with aggressive tendencies or poor social skills.

Mood improvement strategies such as humor and empathy can diffuse anger and reduce the likelihood of aggressive responses. Creating positive work environments that support employee well-being may prevent many counterproductive behaviors from occurring.

Dynamic Nature of Criteria

You might think that once you figure out how to measure performance, you’re set for life. Not so fast! Performance measurement faces the additional complexity that performance levels change over time in both absolute and relative terms. Dynamic criteria represent this phenomenon, where the most effective employees during initial employment periods may not remain the highest performers over extended timeframes.

Performance levels change over time in both absolute and relative ways. Trying to assess a moving target can be quite difficult and affects the validity of our selection batteries. The most effective employees during the first six months on the job are not always the same as those at the end of the next six months.

Absolute changes in performance reflect natural learning curves, where new employees gradually improve their capabilities through experience and skill development. However, relative changes in performance rankings prove more problematic for selection system validation, as they suggest that different individual characteristics may predict performance at different career stages.

Research demonstrates that cognitive ability strongly predicts early job performance when learning requirements are high, but personality characteristics may become more important predictors as employees gain experience and technical skills. These patterns suggest that selection systems optimized for predicting short-term performance may not effectively predict long-term success.

The dynamic nature of criteria affects the validity of selection procedures and raises questions about appropriate timeframes for criterion measurement in validation studies. Should validation focus on performance during the first six months, first year, or longer periods? Different timeframes may favor different selection approaches and lead to different conclusions about predictor effectiveness.

Organizations must consider their primary concerns when designing performance measurement systems. If early productivity and quick learning are most important, criteria should focus on initial performance periods. If long-term retention and career development matter more, longer-term performance measures may be more appropriate.

Media Attributions

- Employee Performance © Manypixels Gallery is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Campbell’s Model of Job Performance © Jay Brown

- Campbell’s Full Model © Jay Brown

- Campbell’s Model of Job Performance © Campbell

- Maximum vs. Typical Job Performance © Jay Brown

- The Eight Great Competencies of Job Performance Part 1

- The Eight Great Competencies of Job Performance Part 2

- Seal of the United States Merit Systems Protection Board © U.S. Government is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Counterproductive Behavior © Jay Brown