6-2: Evaluating Criterion

Ultimate Versus Actual Criteria

Ultimate Versus Actual Criteria

Now we’re getting to one of the most fundamental concepts in criterion measurement theory, and it might just change how you think about performance measurement forever. The distinction between ultimate and actual criteria represents the gap between what we’d ideally like to measure and what we can actually measure in the real world.

The ultimate criterion encompasses all aspects of job performance that define success, representing a comprehensive but abstract ideal that captures perfect measurement of the performance construct. Think of it as the holy grail of performance measurement—if you could measure absolutely everything that contributes to job success, that would be your ultimate criterion.

Thorndike’s classic observation that the ultimate criterion is “very complex and never completely accessible” acknowledges the practical impossibility of measuring every aspect of job performance that contributes to success (Thorndike, 1949). Binning and Barrett (1989) further elaborated on this conceptual framework, noting that the development of criterion measures must consider both the inferential and evidential bases for making personnel decisions. The ultimate criterion resembles an incredibly complex hypothetical construct comprised of multiple interrelated constructs, some of which may be intangible qualities such as charisma, judgment, or leadership presence.

Consider the ultimate criterion for an administrative assistant position. This might include oral communication skills, knowledge of procedures, organizational abilities, supervisory interactions, punctuality, initiative, typing speed and accuracy, filing efficiency, client relations, coworker relationships, and written communication capabilities. Each of these components requires further operational definition, and the list itself represents only a partial enumeration of potentially relevant performance dimensions.

The hypothetical construct of a “good” administrative assistant would involve someone with all these skills. This list is by no means complete, and each skill on the list must be further operationally defined.

The actual criterion represents our best practical approximation of the ultimate criterion, constrained by considerations of cost, time, measurement feasibility, and organizational priorities. The goal in criterion development involves maximizing the overlap between ultimate and actual criteria while maintaining practical utility for organizational decision-making.

In a perfect world, the ultimate criterion would equal the actual criterion. However, practical constraints necessitate choices about which elements to include in operational measurement systems. Because we cannot possibly measure every facet of performance that we think is involved in the administrative assistant job and probably could not list everything that would indicate someone’s success on the job, we consider only those elements that seem most important and that are most easily measured.

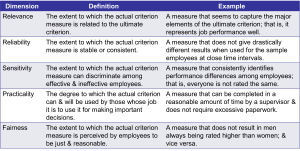

Evaluating Criterion Quality

So how do you know if your performance measure is actually any good? The utility of any criterion depends on several key characteristics that determine its effectiveness for organizational decision-making. These characteristics provide standards for evaluating and comparing different criterion measurement approaches.

Relevance represents the degree to which the actual criterion relates to the ultimate criterion, quantified as the percentage of variance in the ultimate criterion that can be accounted for by the actual criterion. High relevance indicates that the operational measure captures a substantial portion of the theoretical performance construct. Think of it as asking, “Does this measure actually capture what we really care about?”

Criterion deficiency refers to aspects of the ultimate criterion that are not included in the actual criterion measure. The extent of deficiency depends on the importance of excluded elements—if omitted aspects are relatively unimportant, deficiency will be minimal. However, deficiency also includes aspects of the ultimate criterion that researchers failed to identify or consider during criterion development. It’s like having a recipe that’s missing key ingredients.

Criterion contamination occurs when the actual criterion measures aspects that are not part of the ultimate criterion. Contamination takes two primary forms: random measurement error (differences between measured and actual performance due to measurement imprecision) and systematic bias (consistently higher or lower evaluations based on factors unrelated to job performance).

As Binning and Barrett (1989) noted, systematic bias becomes particularly problematic in criterion measurement as it can persist across multiple measurement occasions and artificially inflate criterion-related validity coefficients. Bias becomes particularly troublesome when criteria involve human judgments, as evaluators may be influenced by factors such as physical attractiveness, similarity to themselves, or other characteristics unrelated to job performance. Like hiring attractive people as administrative assistants even though they can’t type. The prevalence of bias in subjective performance measures necessitates careful attention to rater training and measurement standardization.

Reliability concerns the stability and consistency of criterion measurement over time and across measurement occasions. Unreliable criteria produce substantially different results when measured at different time points, making it impossible to determine true performance levels. For example, if typing speed measurements for the same individual vary dramatically (40, 110, 50, 90, 76 words per minute), the unreliability prevents confident conclusions about actual typing ability.

In this example, we don’t know which of these measures reflects the true ability—is this a good typist and 110 wpm reflects it, or a bad typist and 40 wpm reflects this? Unreliable criteria don’t help us because they don’t accurately tell us anything about the underlying construct (is this a good administrative assistant).

Sensitivity requires that criteria be capable of discriminating between effective and ineffective employees. If everyone’s performance is similar, then we cannot use this to discriminate good from bad employees. For instance, if factory workers all produce between 22 and 24 valve stems per hour, this measure lacks sufficient sensitivity for performance evaluation. We’d need to find a more sensitive measure, something that differentiates good from bad performance—perhaps quality of work or amount of waste.

Practicality addresses the extent to which criteria can and will be used by organizational decision-makers. Even the most psychometrically sophisticated criterion proves worthless if organizational stakeholders refuse to use it due to complexity, cost, or other practical barriers. This reminds me of a great museum designed with funky slanting walls—a true architectural masterpiece that cost many millions but made people sick just to be in it. Always consider the people who will use something before you make something! Successful criterion development must consider the perspectives and constraints of those who will implement and use the measurement system.

Fairness captures employees’ perceptions of criterion reasonableness and justice. If employees view performance measures as unfair or biased (such as using cronyism for promotion decisions), negative consequences may include reduced motivation, increased turnover, discrimination complaints, and even workplace violence. Unhappy workers give bad customer service, sue for discrimination, are more likely to commit employee theft, and are more likely to commit workplace violence. Employee perceptions of fairness influence both their willingness to perform well and their acceptance of performance-based decisions.

Objective Criteria

Let’s talk about what seems like the most straightforward approach to measuring performance. Objective criteria (also called hard or nonjudgmental criteria) derive from organizational records and presumably involve minimal subjective judgment in their collection. Common objective criteria include absence rates, turnover, productivity measures, tardiness, and various personnel actions recorded in human resource information systems.

Productivity represents the most typical objective criterion, usually defined as the number of acceptable products produced within a specified time period. This measure appeals to organizations because of its apparent objectivity and direct relationship to organizational output goals. However, productivity measures face several significant limitations that reduce their utility as performance criteria.

Research by Bommer and colleagues (1995) in their comprehensive meta-analysis found that objective and subjective measures of employee performance showed only moderate convergence (corrected correlation of .389), indicating these measurement approaches capture somewhat different aspects of performance. This finding suggests that organizations cannot simply substitute objective measures for subjective ones without potentially missing important performance dimensions.

Productivity measures prove inappropriate for many positions, particularly managerial and professional roles where output cannot be easily quantified. Even in production environments, productivity measures may not account for situational constraints such as equipment availability, material quality, or workflow disruptions that influence individual output independent of personal performance.

Objective criteria also fail to capture important performance dimensions such as cooperation, initiative, problem-solving, and other behaviors that contribute to organizational effectiveness but don’t directly translate into countable outputs. An employee might demonstrate exceptional teamwork and innovation while producing average quantitative output, yet objective measures would rate this person as an average performer.

The apparent objectivity of these measures may be misleading, as decisions about what to count, how to count it, and what constitutes acceptable quality often involve subjective judgments. Even seemingly straightforward measures like absenteeism require decisions about how to treat different types of absences, excused versus unexcused time off, and partial-day absences.

Despite these limitations, objective criteria provide valuable information about certain aspects of job performance and offer advantages in terms of reliability and legal defensibility. When appropriately interpreted and combined with other performance measures, objective criteria can contribute meaningfully to comprehensive performance evaluation systems.

Subjective Criteria

Now let’s flip the script and talk about measures that rely entirely on human judgment. Subjective criteria (also called soft or judgmental criteria) rely on human judgments and evaluations rather than counting objective events. Performance appraisal ratings and rankings represent the most common forms of subjective criteria, involving supervisors, peers, or other stakeholders evaluating employee performance on various dimensions.

Subjective criteria offer several advantages over objective measures. They can be applied to virtually any job, including managerial and professional positions where objective output measures are impractical. Subjective measures can capture complex performance dimensions such as leadership, creativity, problem-solving, and interpersonal effectiveness that resist quantification but critically influence organizational success.

However, the meta-analytic findings by Bommer et al. (1995) also revealed that subjective criteria are susceptible to various biases, attitudes, and beliefs of the individuals providing evaluations. Rater biases including halo effects, leniency or severity errors, central tendency, and various forms of discrimination can substantially influence subjective performance ratings. These biases may reduce the accuracy and fairness of performance evaluations while creating legal vulnerabilities for organizations.

The quality of subjective criteria depends heavily on rater training, evaluation system design, and organizational support for accurate performance assessment. Well-designed subjective measures with trained raters can achieve high reliability and validity, while poorly implemented systems may be worse than no formal evaluation at all.

Organizations typically employ multiple approaches to improve subjective criterion quality, including behaviorally anchored rating scales, forced distribution systems, multi-source feedback, and rater training programs. These interventions can substantially improve the psychometric properties of subjective performance measures while maintaining their flexibility and comprehensiveness.

Personnel Measures

Personnel measures encompass various administrative actions and records that may indicate job performance, including absences, accidents, tardiness, disciplinary actions, and commendations for exceptional performance. These measures often serve as supplementary criteria that provide additional perspectives on employee performance beyond primary productivity or rating measures.

Absence measures require careful interpretation, as different types of absences may have different implications for performance evaluation. Chronic unexcused absences likely indicate performance problems, while occasional absences for family emergencies or medical reasons may be unrelated to job performance. Organizations must develop clear policies about how different absence types factor into performance evaluation.

Accident rates can provide important safety-related performance information, particularly for positions where safety represents a critical job requirement. However, accident measures must account for job exposure levels, workplace hazards, and other factors that influence accident likelihood independent of individual safety performance.

Disciplinary actions and commendations provide information about exceptional performance episodes, both positive and negative. These measures supplement ongoing performance evaluation by highlighting specific incidents that demonstrate particularly effective or problematic performance. However, the frequency and consistency of supervisory recognition may influence the apparent distribution of commendations independent of actual performance differences.

Personnel measures work best when integrated with other performance indicators to provide comprehensive performance evaluation. They shouldn’t serve as primary performance criteria but can provide valuable supplementary information that enhances understanding of overall job performance.

Legal and Ethical Considerations in Criterion Measurement

Here’s something that might surprise you: criterion measurement isn’t just about finding the best measures—it’s also about staying on the right side of the law. Criterion measurement must comply with extensive legal requirements designed to ensure fair and non-discriminatory employment practices. The Civil Rights Act, Americans with Disabilities Act, Age Discrimination in Employment Act, and other legislation establish requirements for criterion development and use.

The National Research Council (1991) emphasizes that organizations must be prepared to provide validation evidence showing that criteria relate to important job requirements and predict meaningful performance outcomes, particularly when adverse impact occurs. The Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures provide detailed requirements for demonstrating the job-relatedness of performance criteria, particularly when they’re used to make employment decisions that affect protected groups differently.

Adverse impact analysis examines whether performance criteria affect protected groups differently, typically using the “80% rule” where performance levels for protected groups should be at least 80% of the rate for the majority group. When adverse impact occurs in criterion measures, organizations must evaluate whether the criteria accurately reflect job requirements or incorporate bias that unfairly disadvantages certain groups.

Privacy considerations become important when criteria involve personal information, medical records, or other sensitive data. Organizations must balance legitimate business needs for performance information against employees’ privacy rights and comply with applicable privacy legislation.

Reasonable accommodation requirements under the ADA may affect criterion measurement for employees with disabilities. Organizations must consider whether performance standards accurately reflect essential job functions and whether accommodations can enable individuals with disabilities to meet legitimate performance requirements.

Media Attributions

- The Criterion © ANDMACRO is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Trying to Catch the Ultimate Criterion © Jay Brown

- What Makes a Good Criterion?