7-3: Performance Appraisal Part 2: Rating Distortions

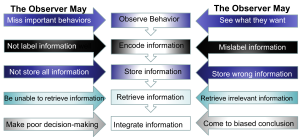

Even well-intentioned managers make systematic errors when rating performance due to inherent limitations in human cognitive processing. Performance appraisal systems encounter various rating errors that occur largely because of cognitive constraints. It’s not that managers are incompetent or malicious—it’s that human brains have predictable quirks that affect how we process and remember information about other people’s performance.

Even well-intentioned managers make systematic errors when rating performance due to inherent limitations in human cognitive processing. Performance appraisal systems encounter various rating errors that occur largely because of cognitive constraints. It’s not that managers are incompetent or malicious—it’s that human brains have predictable quirks that affect how we process and remember information about other people’s performance.

Understanding these errors is crucial for developing better systems and training programs. Think of rating errors as optical illusions for performance evaluation—even when you know they exist, they can still fool you if you’re not careful.

Halo Error

Halo error manifests in two primary ways: when evaluators use overall impressions to rate specific dimensions, and when they resist recognizing differences between various performance aspects. This resembles rating someone highly across all areas simply because of general favorability, even in areas where they lack particular strength.

It’s like meeting someone who’s really funny and automatically assuming they’re also smart, organized, and good at sports. The “halo” of one positive trait spreads to everything else. Halo effects occur especially when evaluators lack job knowledge and familiarity with rated individuals. This error appears more frequently in peer ratings than supervisor ratings of direct reports. The phenomenon can be positive (“halo”) or negative (“pitchfork effect”).

Research distinguishes between “true halo” (legitimate high performance across areas) and “halo error” (unjustified high ratings). Some individuals genuinely demonstrate competence across all areas, making high correlations among performance dimensions legitimate rather than biased. The key involves determining when high ratings are deserved versus favoritism.

Here’s a practical tip: Halo errors can be reduced by having supervisors rate different traits at separate times, such as rating attendance one day and dependability the next. It’s like forcing yourself to think about each aspect independently rather than letting your overall impression color everything.

Distributional Errors

Distributional errors encompass leniency, central tendency, and severity errors—the three primary ways people misuse rating scales. These errors are called “distributional” because they affect how ratings are distributed across the scale.

Leniency

Leniency occurs when evaluators consistently provide higher ratings than justified, often due to liking rated individuals, seeking to be liked, or maintaining workplace peace. Research indicates supervisors uncomfortable with negative employee reactions demonstrate more leniency than those who handle conflict effectively.

It’s like being the teacher who gives everyone A’s because you don’t want students to be upset. Naturally agreeable individuals show more leniency than conscientious ones, which makes sense—agreeable people want to make everyone happy, even if it means inflating ratings. Leniency may be intentional or result from unconscious information processing biases.

Central Tendency Errors

Central tendency errors happen when evaluators use only the middle rating scale portions, potentially due to limited experience with rated individuals, laziness, or fear of discriminating among employees. This error appears to be the default response since the most common score in distributions is the average.

It’s like always answering “C” on multiple choice tests when you don’t know the answer. Some managers take this approach because it feels safe—you’re not calling anyone terrible, but you’re also not identifying anyone as exceptional.

Severity Errors

Severity errors represent the opposite pattern, with evaluators using only low scale portions, possibly to motivate employees, maintain control impressions, or establish improvement baselines. Some managers believe low ratings motivate people or provide foundations for demonstrating later improvement.

This is like the coach who thinks the best way to motivate players is to tell them they’re all terrible. While some people might respond to this approach, research suggests it’s generally counterproductive.

The fundamental problem with distributional errors is that ratings fail to adequately differentiate between effective and ineffective employees. When used for personnel decisions, they cannot provide adequate information, leading to morale problems and unfairness perceptions.

Other Rating Errors

Performance appraisal is susceptible to several other systematic errors that can undermine accuracy and fairness:

Similar-to-me errors occur when evaluators provide more favorable ratings to individuals they perceive as similar to themselves. Humans naturally tend to like people who remind them of themselves, but this can lead to unfair evaluations. It’s like preferring job candidates who went to your alma mater or share your hobbies, even when these factors aren’t relevant to job performance.

Proximity errors happen when ratings on one dimension affect ratings on other dimensions simply because they appear physically close on evaluation forms. If “punctuality” appears right next to “dependability” on a form, a high rating on one might unconsciously influence the rating on the other.

Contrast errors appear when one person’s performance rating gets influenced by whoever was evaluated immediately before them. If evaluated immediately after the best company employee, performance might appear poor by comparison. It’s like how a decent singer might sound terrible if they perform right after Beyoncé.

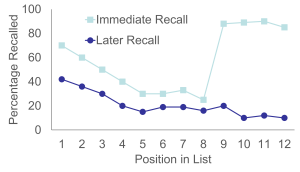

Recency errors reflect evaluators’ tendencies to rely heavily on recent interactions when rating performance, while first impression errors (primacy effects) involve overemphasizing initial experiences with rated individuals. Most of us can relate to this—we remember what happened last week more clearly than what happened six months ago, even though both periods should count equally in an annual review.

Rater Training

Organizations can address rating errors through comprehensive training programs. The question is: what kind of training actually works?

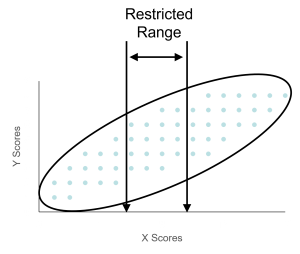

Psychometric training aims to reduce errors by creating awareness, though research by Bernardin and Pence (1980) revealed something interesting: when evaluators are instructed to avoid leniency and halo errors, they do avoid them, but resulting ratings are sometimes less accurate than without training. It’s like telling someone not to think about elephants—sometimes awareness of bias can create overcorrection.

Frame of Reference (FOR) training focuses on improving observation and categorization skills by providing common standards to increase consistency. This approach provides behavioral descriptions of “perfect” employees and improves accuracy by ensuring all evaluators use identical measuring standards.

Think of FOR training as calibrating instruments in a laboratory—you want all the thermometers to read the same temperature when measuring the same thing. Combining FOR training with behavioral observation training might improve recognition and memory of relevant behaviors.

Rater Considerations

Evaluators might have different goals for various reasons. When held accountable for specific objectives like rating accuracy, they provide ratings consistent with those goals. Research shows highly conscientious evaluators are more affected by accountability pressures, while evaluators under stress produce more erroneous ratings than non-stressed evaluators.

This makes intuitive sense—when you’re stressed or distracted, you’re more likely to rely on mental shortcuts and unconscious biases rather than careful, systematic evaluation.

Media Attributions

- Error © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Rating Errors © Jay Brown

- Range Restriction © Jay Brown

- Serial Position Effect © Jay Brown