7-4: Performance Appraisal Part 3: Feedback

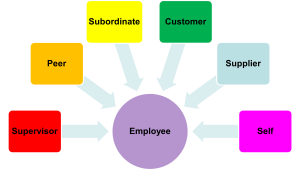

360-Degree Feedback

Traditional performance evaluation has evolved from supervisor-only assessments to comprehensive systems gathering input from multiple sources. The 360-degree feedback approach involves ratings from direct reports, peers, supervisors, clients, and self-evaluations, providing more complete performance pictures.

Think of it like getting restaurant reviews from multiple sources instead of just one food critic. The idea is that different people see different aspects of your performance, and combining these perspectives gives a more accurate overall picture.

Supervisor Feedback

Supervisors often hesitate to evaluate performance and provide feedback for several reasons identified by Fried, Tiegs, and Bellamy (1992): duration of reporting relationship (less time leads to more reluctance), employee experience levels (less experience results in more corrective feedback and greater reluctance), and trust levels between supervisor and employee (lower trust leads to more challenges and evaluation reluctance).

It’s like being reluctant to give constructive criticism to someone you barely know versus someone you’ve worked with for years. Supervisors also face time constraints, since idealized performance management systems require substantial time investment. Ironically, effective performance management ultimately makes managers’ jobs easier by improving employee performance, but the upfront investment can be daunting.

Fear of conflict represents another barrier—some managers fear lawsuits, employee reactions, or just uncomfortable conversations. Nobody enjoys telling someone they’re not meeting expectations, especially when they know it might lead to tears, arguments, or defensive behavior.

Peer Feedback

Peer feedback offers unique advantages since coworkers interact daily and observe typical performance patterns. Peers also observe interpersonal skill interactions, providing valuable information about collaborative abilities. Colleagues see behavior when supervisors aren’t present—they know genuine helpfulness versus performative behavior.

Your coworkers know whether you’re actually helpful or just good at looking busy when the boss walks by. They see how you handle stress, how you treat people who can’t help your career, and whether you follow through on commitments when nobody’s watching.

However, peer ratings face challenges when colleagues are geographically separated, particularly with remote work arrangements. When peer ratings are used for administrative purposes like promotions or pay increases, conflicts of interest emerge since peers might compete for the same limited resources. It’s hard to give honest feedback about someone when you’re both competing for the same promotion.

Self-Ratings

Self-ratings serve important performance management functions, often involving employees completing rating forms and bringing them to supervisor meetings. Comparisons between self-ratings and supervisor ratings provide discussion points, with final ratings placed in personnel files after discussion. This approach increases fairness perceptions and employee involvement.

Self-ratings are interesting because most people have systematic biases about their own performance. We tend to remember our successes more clearly than our failures, and we’re often unaware of how our behavior affects others. But self-ratings can also reveal important insights about employee perceptions and motivations that supervisors might miss.

Subordinate Feedback

Research by Bernardin, Dahmus, and Redmon (1993) found that supervisors support subordinate feedback as long as it’s not used for administrative decisions. Subordinate performance evaluations encourage considering challenges and performance demands supervisors face. These evaluations must remain anonymous to prevent retaliation, as noted by Hedge and Borman (1995).

Think about it—who better to evaluate a manager’s effectiveness than the people who work for them every day? Subordinates know whether their manager provides clear direction, supports their development, and creates a positive work environment. But the feedback has to be anonymous, or you’ll just get a bunch of glowing reviews from people who are afraid of retaliation.

Other Feedback Sources

Beyond the traditional sources of supervisor, peer, and subordinate feedback, modern performance management increasingly incorporates perspectives from external stakeholders who interact with employees in different capacities.

Customer Feedback provides invaluable insights into employee performance from the perspective of those who receive services or products. This feedback is particularly valuable for customer-facing roles like sales representatives, customer service agents, account managers, and retail workers. Customer feedback can be collected through satisfaction surveys, complaint/compliment systems, mystery shopper programs, or online reviews. The advantage is that customers see how employees actually behave when representing the organization, often revealing performance aspects that internal observers might miss. However, customer feedback can be influenced by factors beyond employee control, such as product quality, company policies, or situational circumstances.

Vendor and Supplier Feedback offers unique perspectives on how employees manage external relationships, negotiate contracts, communicate requirements, and handle business partnerships. This feedback is especially relevant for procurement specialists, project managers, account managers, and anyone who regularly interfaces with external business partners. Vendors can provide insights into an employee’s professionalism, communication effectiveness, problem-solving abilities, and relationship management skills. Since vendors often have long-term relationships with organizations, they can observe performance patterns over time and across different situations.

Internal Customer Feedback comes from other departments or teams within the organization who receive services from the employee being evaluated. For example, IT support staff might receive feedback from employees they’ve helped, HR professionals might get input from managers they’ve supported with hiring or policy issues, and finance team members might receive feedback from departments they’ve assisted with budgeting or reporting. This internal customer perspective reveals how well employees serve the broader organization beyond their immediate work group.

Client Feedback differs from general customer feedback in that it typically involves more sustained, professional relationships. Consultants, lawyers, accountants, therapists, and other professional service providers often receive detailed feedback from clients about their expertise, communication skills, responsiveness, and overall service quality. Client feedback tends to be more nuanced and relationship-focused than transactional customer feedback.

The challenge with external feedback sources is ensuring consistency and fairness in collection methods, managing potential conflicts of interest, and accounting for factors beyond the employee’s control that might influence external perceptions. However, when properly implemented, these additional feedback sources provide a more complete picture of employee performance and impact.

360-Degree Feedback Implementation

360-degree feedback systems rest on three basic assumptions: participants are happier when multiple evaluators are involved, multiple evaluators overcome individual quirks or biases, and multiple evaluators provide broader and more accurate performance views.

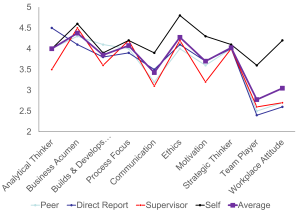

These assumptions make intuitive sense, but implementing 360-degree feedback successfully requires careful planning and execution. Successful implementation requires honesty about rating usage, helping employees interpret and handle ratings, avoiding information overload, training all evaluators including self-raters, and potentially outsourcing process components.

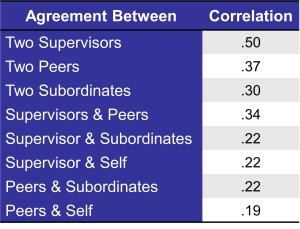

Most research on 360-degree feedback has focused on measurement properties and agreement among different rating sources. The reality is that different sources often disagree significantly, which raises questions about which perspectives are most accurate or valuable.

The Feedback Process and Environment

Employee development depends largely on feedback receptivity and organizational feedback approaches. Continuous employee development represents an ongoing cycle where employees are motivated to plan for and engage in actions benefiting future employability regularly.

But here’s the thing about feedback: it’s not enough to just give it. People have to be willing and able to receive it, process it, and act on it. That’s where the feedback environment becomes crucial.

Key Steps in Feedback Processing

The feedback process involves three key steps: paying attention to feedback, processing feedback, and actually using it. According to Feedback Intervention Theory (FIT), feedback works best when targeted at tasks rather than individuals. A meta-analysis by Kluger and Denisi (1996) found moderate feedback effects on performance, emphasizing proper feedback design and delivery importance.

All three steps are essential for effective feedback use. If any step gets ignored or handled poorly, feedback-related problems like misunderstandings, anxiety, confusion, and poor behavioral choices likely result. It’s like having a three-legged stool—remove any leg and the whole thing collapses.

Feedback Environment

The feedback environment reflects organizational culture and specifically represents organizational climate and attitudes toward feedback. This environment includes source credibility, feedback quality, feedback delivery, and other factors influencing feedback reception and processing.

Strong feedback environments link to satisfaction with and motivation to use feedback, high organizational commitment and citizenship behavior levels, feedback seeking, and role clarity. Organizations with positive feedback environments show higher employee engagement and performance outcomes.

Think about the difference between working in an organization where feedback is seen as an opportunity for growth versus one where it feels like punishment. The same information can be helpful or harmful depending on how it’s delivered and received.

Feedback Orientation

Feedback Orientation (FO) represents overall feedback attitudes or receptivity levels. This includes perceptions of feedback usefulness, accountability to use feedback, social awareness through feedback, and confidence in dealing with feedback.

FO relates to other individual differences like learning goal orientation. Employees high on feedback orientation tend to seek feedback more often than those low on FO. Research shows older workers have higher social awareness aspects and lower utility aspects of FO compared to younger workers, suggesting age-related differences in feedback preferences and processing.

It makes sense that people differ in their receptivity to feedback—some people actively seek it out, while others avoid it like the plague. Understanding these individual differences can help managers tailor their approach to be more effective.

Media Attributions

- Feedback © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Multi-Source Feedback © Jay Brown

- Rater Agreement

- Multi-Source Feeback Profile © Jay Brown

Performance evaluation approach that gathers input from multiple sources—supervisors, peers, subordinates, and sometimes customers—rather than just from your direct boss. (Modules 01, 07)