14-1 Emotion

OpenStax Psychology 2e

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the major theories of emotion

- Describe the role that limbic structures play in emotional processing

- Understand the ubiquitous nature of producing and recognizing emotional expression

As we move through our daily lives, we experience a variety of emotions. An emotion is a subjective state of being that we often describe as our feelings. Emotions result from the combination of subjective experience, expression, cognitive appraisal, and physiological responses (Levenson, Carstensen, Friesen, & Ekman, 1991). However, as discussed later in the chapter, the exact order in which the components occur is not clear, and some parts may happen at the same time. An emotion often begins with a subjective (individual) experience, which is a stimulus. Often the stimulus is external, but it does not have to be from the outside world. For example, it might be that one thinks about war and becomes sad, even though they never experienced war. Emotional expression refers to the way one displays an emotion and includes nonverbal and verbal behaviors (Gross, 1999). One also performs a cognitive appraisal in which a person tries to determine the way they will be impacted by a situation (Roseman & Smith, 2001). In addition, emotions include physiological responses, such as possible changes in heart rate, sweating, etc. (Soussignan, 2002).

The words emotion and mood are sometimes used interchangeably, but psychologists use these words to refer to two different things. Typically, the word emotion indicates a subjective, affective state that is relatively intense and that occurs in response to something we experience (Figure 10.20). Emotions are often thought to be consciously experienced and intentional. Mood, on the other hand, refers to a prolonged, less intense, affective state that does not occur in response to something we experience. Mood states may not be consciously recognized and do not carry the intentionality that is associated with emotion (Beedie, Terry, Lane, & Devonport, 2011). Here we will focus on emotion, and you will learn more about mood in the chapter that covers psychological disorders.

Figure 10.20: Toddlers can cycle through emotions quickly, being (a) extremely happy one moment and (b) extremely sad the next. (credit a: modification of work by Kerry Ceszyk; credit b: modification of work by Kerry Ceszyk)

Figure 10.20: Toddlers can cycle through emotions quickly, being (a) extremely happy one moment and (b) extremely sad the next. (credit a: modification of work by Kerry Ceszyk; credit b: modification of work by Kerry Ceszyk)We can be at the heights of joy or in the depths of despair. We might feel angry when we are betrayed, fear when we are threatened, and surprised when something unexpected happens. This section will outline some of the most well-known theories explaining our emotional experience and provide insight into the biological bases of emotion. This section closes with a discussion of the ubiquitous nature of facial expressions of emotion and our abilities to recognize those expressions in others.

Theories of Emotion

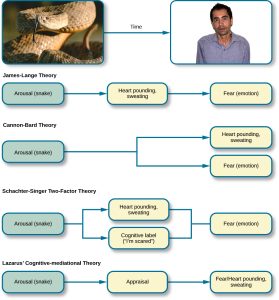

Our emotional states are combinations of physiological arousal, psychological appraisal, and subjective experiences. Together, these are the components of emotion, and our experiences, backgrounds, and cultures inform our emotions. Therefore, different people may have different emotional experiences even when faced with similar circumstances. Over time, several different theories of emotion, shown in Figure 10.21, have been proposed to explain how the various components of emotion interact with one another.

Figure 10.21: This figure illustrates the major assertions of the James-Lange, Cannon-Bard, and Schachter-Singer two-factor theories of emotion. (credit “snake”: modification of work by “tableatny”/Flickr; credit “face”: modification of work by Cory Zanker)

Figure 10.21: This figure illustrates the major assertions of the James-Lange, Cannon-Bard, and Schachter-Singer two-factor theories of emotion. (credit “snake”: modification of work by “tableatny”/Flickr; credit “face”: modification of work by Cory Zanker)The James-Lange theory of emotion asserts that emotions arise from physiological arousal. Recall what you have learned about the sympathetic nervous system and our fight or flight response when threatened. If you were to encounter some threat in your environment, like a venomous snake in your backyard, your sympathetic nervous system would initiate significant physiological arousal, which would make your heart race and increase your respiration rate. According to the James-Lange theory of emotion, you would only experience a feeling of fear after this physiological arousal had taken place. Furthermore, different arousal patterns would be associated with different feelings.

Other theorists, however, doubted that the physiological arousal that occurs with different types of emotions is distinct enough to result in the wide variety of emotions that we experience. Thus, the Cannon-Bard theory of emotion was developed. According to this view, physiological arousal and emotional experience occur simultaneously, yet independently (Lang, 1994). So, when you see the venomous snake, you feel fear at exactly the same time that your body mounts its fight or flight response. This emotional reaction would be separate and independent of the physiological arousal, even though they co-occur.

Does smiling make you happy? Alternatively, does being happy make you smile? The facial feedback hypothesis proposes that your facial expression can actually affect your emotional experience (Adelman & Zajonc, 1989; Boiger & Mesquita, 2012; Buck, 1980; Capella, 1993; Soussignan, 2001). Research investigating the facial feedback hypothesis suggested that suppression of facial expression of emotion lowered the intensity of some emotions experienced by participants (Davis, Senghas, & Ochsner, 2009). Havas, Glenberg, Gutowski, Lucarelli, and Davidson (2010) used Botox injections to paralyze facial muscles and limit facial expressions, including frowning, and they found that depressed people reported less depression after their frowning muscles were paralyzed. Other research found that the intensities of facial expressions affected the emotional reactions (Soussignan, 2002). In other words, if something insignificant occurs and you smile as if you just won lottery, you will actually be happier about the little thing than you would be if you only had a tiny smile. Conversely, if you walk around frowning all the time, it might cause you to have less positive emotions than you would if you had smiled. Interestingly, Soussignan (2002) also reported physiological arousal differences associated with the intensities of one type of smile.

G. Marañon Posadillo was a Spanish physician who studied the psychological effects of adrenaline to create a model for the experience of emotion. Marañon’s model preceded Schachter’s two-factor or arousal-cognition theory of emotion (Cornelius, 1991). The Schachter-Singer two-factor theory of emotion is another variation on theories of emotions that takes into account both physiological arousal and the emotional experience. According to this theory, emotions are composed of two factors: physiological and cognitive. In other words, physiological arousal is interpreted in context to produce the emotional experience. In revisiting our example involving the venomous snake in your backyard, the two-factor theory maintains that the snake elicits sympathetic nervous system activation that is labeled as fear given the context, and our experience is that of fear. If you had labeled your sympathetic nervous system activation as joy, you would have experienced joy. The Schachter-Singer two-factor theory depends on labeling the physiological experience, which is a type of cognitive appraisal.

Magda Arnold was the first theorist to offer an exploration of the meaning of appraisal, and to present an outline of what the appraisal process might be and how it relates to emotion (Roseman & Smith, 2001). The key idea of appraisal theory is that you have thoughts (a cognitive appraisal) before you experience an emotion, and the emotion you experience depends on the thoughts you had (Frijda, 1988; Lazarus, 1991). If you think something is positive, you will have more positive emotions about it than if your appraisal was negative, and the opposite is true. Appraisal theory explains the way two people can have two completely different emotions regarding the same event. For example, suppose your psychology instructor selected you to lecture on emotion; you might see that as positive, because it represents an opportunity to be the center of attention, and you would experience happiness. However, if you dislike speaking in public, you could have a negative appraisal and experience discomfort.

Schachter and Singer believed that physiological arousal is very similar across the different types of emotions that we experience, and therefore, the cognitive appraisal of the situation is critical to the actual emotion experienced. In fact, it might be possible to misattribute arousal to an emotional experience if the circumstances were right (Schachter & Singer, 1962). They performed a clever experiment to test their idea. A group of men participating in the experiment were randomly assigned to one of several groups. Some of the participants received injections of epinephrine that caused bodily changes that mimicked the fight-or-flight response of the sympathetic nervous system; however, only some of these men were told to expect these reactions as side effects of the injection. The other men that received injections of epinephrine were told either that the injection would have no side effects or that it would result in a side effect unrelated to a sympathetic response, such as itching feet or headache. After receiving these injections, participants waited in a room with someone else they thought was another subject in the research project. In reality, the other person was a confederate (someone working on behalf) of the researcher. The confederate engaged in scripted displays of euphoric or angry behavior (Schachter & Singer, 1962).

When those participants who were told that they should expect to feel symptoms of physiological arousal were asked about any emotional changes that they had experienced related to either euphoria or anger (depending on the way the confederate behaved), they reported none. However, the men who weren’t expecting physiological arousal as a function of the injection were more likely to report that they experienced euphoria or anger as a function of their assigned confederate’s behavior. While everyone who received an injection of epinephrine experienced the same physiological arousal, only those who were not expecting the arousal used context to interpret the arousal as a change in emotional state (Schachter & Singer, 1962).

Strong emotional responses are associated with strong physiological arousal, which caused some theorists to suggest that the signs of physiological arousal, including increased heart rate, respiration rate, and sweating, might be used to determine whether someone is telling the truth or not. The assumption is that most of us would show signs of physiological arousal if we were being dishonest with someone. A polygraph, or lie detector test, measures the physiological arousal of an individual responding to a series of questions. Someone trained in reading these tests would look for answers to questions that are associated with increased levels of arousal as potential signs that the respondent may have been dishonest on those answers. While polygraphs are still commonly used, their validity and accuracy are highly questionable because there is no evidence that lying is associated with any particular pattern of physiological arousal (Saxe & Ben-Shakhar, 1999).

The relationship between our experiencing of emotions and our cognitive processing of them, and the order in which these occur, remains a topic of research and debate. Lazarus (1991) developed the cognitive-mediational theory that asserts our emotions are determined by our appraisal of the stimulus. This appraisal mediates between the stimulus and the emotional response, and it is immediate and often unconscious. In contrast to the Schachter-Singer model, the appraisal precedes a cognitive label. You will learn more about Lazarus’s appraisal concept when you study stress, health, and lifestyle. However, there are other views of emotions that also emphasize the cognitive processes.

Return to the example of being asked to lecture by your professor. Even if you do not enjoy speaking in public, you probably could manage to do it. You would purposefully control your emotions, which would allow you to speak, but we constantly regulate our emotions, and much of our emotion regulation occurs without us actively thinking about it. Mauss and her colleagues studied automatic emotion regulation (AER), which refers to the non-deliberate control of emotions. It is simply not reacting with your emotions, and AER can affect all aspects of emotional processes. AER can influence the things you attend to, your appraisal, your choice to engage in an emotional experience, and your behaviors after an emotion is experienced (Mauss, Bunge, & Gross, 2007; Mauss, Levenson, McCarter, Wilhelm, & Gross, 2005). AER is similar to other automatic cognitive processes in which sensations activate knowledge structures that affect functioning. These knowledge structures can include concepts, schemas, or scripts.

The idea of AER is that people develop an automatic process that works like a script or schema, and the process does not require deliberate thought to regulate emotions. AER works like riding a bicycle. Once you develop the process, you just do it without thinking about it. AER can be adaptive or maladaptive and has important health implications (Hopp, Troy, & Mauss, 2011). Adaptive AER leads to better health outcomes than maladaptive AER, primarily due to experiencing or mitigating stressors better than people with maladaptive AERs (Hopp, Troy, & Mauss, 2011). Alternatively, maladaptive AERs may be critical for maintaining some psychological disorders (Hopp, Troy, & Mauss, 2011). Mauss and her colleagues found that strategies could reduce negative emotions, which in turn should increase psychological health (Mauss, Cook, Cheng, & Gross, 2007; Mauss, Cook, & Gross, 2007; Shallcross, Troy, Boland, & Mauss, 2010; Troy, Shallcross, & Mauss, 2013; Troy, Wilhelm, Shallcross, & Mauss, 2010). Mauss has also suggested there are problems with the way emotions are measured, but she believes most of the aspects of emotions that are typically measured are useful (Mauss, et al., 2005; Mauss & Robinson, 2009). However, another way of considering emotions challenges our entire understanding of emotions.

After about three decades of interdisciplinary research, Barrett argued that we do not understand emotions. She proposed that emotions were not built into your brain at birth, but rather they were constructed based on your experiences. Emotions in the constructivist theory are predictions that construct your experience of the world. In the chapter on Thinking and Intelligence you learned that concepts are categories or groupings of linguistic information, images, ideas, or memories, such as life experiences. Barrett extended that to include emotions as concepts that are predictions (Barrett, 2017). Two identical physiological states can result in different emotional states depending on your predictions. For example, your brain predicting a churning stomach in a bakery could lead to you constructing hunger. However, your brain predicting a churning stomach while you were waiting for medical test results could lead your brain to construct worry. Thus, you can construct two different emotions from the same physiological sensations. Rather than emotions being something over which you have no control, you can control and influence your emotions.

Link to Learning

Watch this video in which Dr. Barrett explains constructed emotions to learn more.

Two other prominent views arise from the work of Robert Zajonc and Joseph LeDoux. Zajonc asserted that some emotions occur separately from or prior to our cognitive interpretation of them, such as feeling fear in response to an unexpected loud sound (Zajonc, 1998). He also believed in what we might casually refer to as a gut feeling—that we can experience an instantaneous and unexplainable like or dislike for someone or something (Zajonc, 1980). LeDoux also views some emotions as requiring no cognition: some emotions completely bypass contextual interpretation. His research into the neuroscience of emotion has demonstrated the amygdala’s primary role in fear (Cunha, Monfils, & LeDoux, 2010; LeDoux 1996, 2002). A fear stimulus is processed by the brain through one of two paths: from the thalamus (where it is perceived) directly to the amygdala or from the thalamus through the cortex and then to the amygdala. The first path is quick, while the second enables more processing about details of the stimulus. In the following section, we will look more closely at the neuroscience of emotional response.

The Biology of Emotions

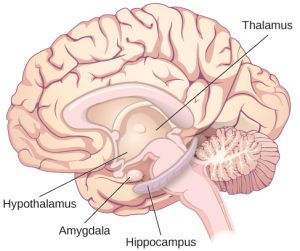

Earlier, you learned about the limbic system, which is the area of the brain involved in emotion and memory (Figure 10.22). The limbic system includes the hypothalamus, thalamus, amygdala, and the hippocampus. The hypothalamus plays a role in the activation of the sympathetic nervous system that is a part of any given emotional reaction. The thalamus serves as a sensory relay center whose neurons project to both the amygdala and the higher cortical regions for further processing. The amygdala plays a role in processing emotional information and sending that information on (Fossati, 2012). The hippocampus integrates emotional experience with cognition (Femenía, Gómez-Galán, Lindskog, & Magara, 2012).

Figure 10.22: The limbic system, which includes the hypothalamus, thalamus, amygdala, and the hippocampus, is involved in mediating emotional response and memory.

Figure 10.22: The limbic system, which includes the hypothalamus, thalamus, amygdala, and the hippocampus, is involved in mediating emotional response and memory.Link to Learning

Work through this Open Colleges interactive 3D brain simulator for a refresher on the brain’s parts and their functions. To begin, click the “Start Exploring” button. To access the limbic system, click the plus sign in the right-hand menu (set of three tabs).

Amygdala

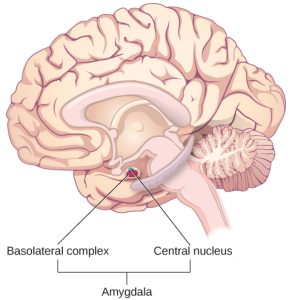

The amygdala has received a great deal of attention from researchers interested in understanding the biological basis for emotions, especially fear and anxiety (Blackford & Pine, 2012; Goosens & Maren, 2002; Maren, Phan, & Liberzon, 2013). The amygdala is composed of various subnuclei, including the basolateral complex and the central nucleus (Figure 10.23). The basolateral complex has dense connections with a variety of sensory areas of the brain. It is critical for classical conditioning and for attaching emotional value to learning processes and memory. The central nucleus plays a role in attention, and it has connections with the hypothalamus and various brainstem areas to regulate the autonomic nervous and endocrine systems’ activity (Pessoa, 2010).

Figure 10.23: The anatomy of the basolateral complex and central nucleus of the amygdala are illustrated in this diagram.

Figure 10.23: The anatomy of the basolateral complex and central nucleus of the amygdala are illustrated in this diagram.Animal research has demonstrated that there is increased activation of the amygdala in rat pups that have odor cues paired with electrical shock when their mother is absent. This leads to an aversion to the odor cue that suggests the rats learned to fear the odor cue. Interestingly, when the mother was present, the rats actually showed a preference for the odor cue despite its association with an electrical shock. This preference was associated with no increases in amygdala activation. This suggests a differential effect on the amygdala by the context (the presence or absence of the mother) determined whether the pups learned to fear the odor or to be attracted to it (Moriceau & Sullivan, 2006).

Raineki, Cortés, Belnoue, and Sullivan (2012) demonstrated that, in rats, negative early life experiences could alter the function of the amygdala and result in adolescent patterns of behavior that mimic human mood disorders. In this study, rat pups received either abusive or normal treatment during postnatal days 8–12. There were two forms of abusive treatment. The first form of abusive treatment had an insufficient bedding condition. The mother rat had insufficient bedding material in her cage to build a proper nest that resulted in her spending more time away from her pups trying to construct a nest and less time nursing her pups. The second form of abusive treatment had an associative learning task that involved pairing odors and an electrical stimulus in the absence of the mother, as described above. The control group was in a cage with sufficient bedding and was left undisturbed with their mothers during the same time period. The rat pups that experienced abuse were much more likely to exhibit depressive-like symptoms during adolescence when compared to controls. These depressive-like behaviors were associated with increased activation of the amygdala.

Human research also suggests a relationship between the amygdala and psychological disorders of mood or anxiety. Changes in amygdala structure and function have been demonstrated in adolescents who are either at-risk or have been diagnosed with various mood and/or anxiety disorders (Miguel-Hidalgo, 2013; Qin et al., 2013). It has also been suggested that functional differences in the amygdala could serve as a biomarker to differentiate individuals suffering from bipolar disorder from those suffering from major depressive disorder (Fournier, Keener, Almeida, Kronhaus, & Phillips, 2013).

Hippocampus

As mentioned earlier, the hippocampus is also involved in emotional processing. Like the amygdala, research has demonstrated that hippocampal structure and function are linked to a variety of mood and anxiety disorders. Individuals suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) show marked reductions in the volume of several parts of the hippocampus, which may result from decreased levels of neurogenesis and dendritic branching (the generation of new neurons and the generation of new dendrites in existing neurons, respectively) (Wang et al., 2010). While it is impossible to make a causal claim with correlational research like this, studies have demonstrated behavioral improvements and hippocampal volume increases following either pharmacological or cognitive-behavioral therapy in individuals suffering from PTSD (Bremner & Vermetten, 2004; Levy-Gigi, Szabó, Kelemen, & Kéri, 2013).

Facial Expression and Recognition of Emotions

Culture can impact the way in which people display emotion. A cultural display rule is one of a collection of culturally specific standards that govern the types and frequencies of displays of emotions that are acceptable (Malatesta & Haviland, 1982). Therefore, people from varying cultural backgrounds can have very different cultural display rules of emotion. For example, research has shown that individuals from the United States express negative emotions like fear, anger, and disgust both alone and in the presence of others, while Japanese individuals only do so while alone (Matsumoto, 1990). Furthermore, individuals from cultures that tend to emphasize social cohesion are more likely to engage in suppression of emotional reaction so they can evaluate which response is most appropriate in a given context (Matsumoto, Yoo, & Nakagawa, 2008).

Other distinct cultural characteristics might be involved in emotionality. For instance, there may be gender differences involved in emotional processing. While research into gender differences in emotional display is equivocal, there is some evidence that people of different genders may differ in regulation of emotions (McRae, Ochsner, Mauss, Gabrieli, & Gross, 2008).

Paul Ekman (1972) researched a New Guinea man who was living in a preliterate culture using stone implements, and which was isolated and had never seen any outsiders before. Ekman asked the man to show what his facial expression would be if: (1) friends visited, (2) his child had just died, (3) he was about to fight, (4) he stepped on a smelly dead pig. After Ekman’s return from New Guinea, he researched facial expressions for more than four decades. Despite different emotional display rules, our ability to recognize and produce facial expressions of emotion appears to be universal. In fact, even congenitally blind individuals produce the same facial expression of emotions, despite their never having the opportunity to observe these facial displays of emotion in other people. This would seem to suggest that the pattern of activity in facial muscles involved in generating emotional expressions is universal, and indeed, this idea was suggested in the late 19th century in Charles Darwin’s book The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). In fact, there is substantial evidence for seven universal emotions that are each associated with distinct facial expressions. These include: happiness, surprise, sadness, fright, disgust, contempt, and anger (Figure 10.24) (Ekman & Keltner, 1997).

Figure 10.24: The seven universal facial expressions of emotion are shown. (credit: modification of work by Cory Zanker)

Figure 10.24: The seven universal facial expressions of emotion are shown. (credit: modification of work by Cory Zanker)Of course, emotion is not only displayed through facial expression. We also use the tone of our voices, various behaviors, and body language to communicate information about our emotional states. Body language is the expression of emotion in terms of body position or movement. Research suggests that we are quite sensitive to the emotional information communicated through body language, even if we’re not consciously aware of it (de Gelder, 2006; Tamietto et al., 2009).

Link to Learning

Watch this short CNN video about body language in the tense situation of a political debate to learn more. Watch this video to learn how to apply the same concepts to more everyday situations.

Connect the Concepts

Emotional Expression and Emotion Regulation

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a set of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by repetitive behaviors and communication and social problems. Children who have autism spectrum disorders have difficulty recognizing the emotional states of others, and research has shown that this may stem from an inability to distinguish various nonverbal expressions of emotion (i.e., facial expressions) from one another (Hobson, 1986). In addition, there is evidence to suggest that autistic individuals also have difficulty expressing emotion through tone of voice and by producing facial expressions (Macdonald et al., 1989). Difficulties with emotional recognition and expression may contribute to the behaviors that characterize autism; therefore, various therapeutic approaches have been explored to address these difficulties. Various educational curricula, cognitive-behavioral therapies, and pharmacological therapies have shown some promise in helping autistic individuals process emotionally relevant information (Bauminger, 2002; Golan & Baron-Cohen, 2006; Guastella et al., 2010).

Emotion regulation describes how people respond to situations and experiences by modifying their emotional experiences and expressions. Covert emotion regulation strategies are those that occur within the individual, while overt strategies involve others or actions (such as seeking advice or consuming alcohol). Aldao and Dixon (2014) studied the relationship between overt emotional regulation strategies and psychopathology. They researched how 218 undergraduate students reported their use of covert and overt strategies and their reported symptoms associated with selected mental disorders, and found that overt emotional regulation strategies were better predictors of psychopathology than covert strategies. Another study examined the relationship between pregaming (the act of drinking heavily before a social event) and two emotion regulation strategies to understand how these might contribute to alcohol-related problems; results suggested a relationship but a complicated one (Pederson, 2016). Further research is needed in these areas to better understand patterns of adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation (Aldao & Dixon-Gordon, 2014).

Media Attributions

- 14 Figure 10.20

- 14 Figure 10.22

- 14 Figure 10-23

- 14 Figure 10.23