Decision-Making

Module 09 Reading

Chapter 14—Beyond Traditional Learning: Understanding Human Decision- Making

I. Studying Choice in the Laboratory

A. Procedures for Measuring Choice in Animals and Humans

Box 14-1

B. The Matching Law as a Description of Choice Behavior

Think Ahead 14-1

C. Theories to Explain Choice Behavior Arising from Laboratory Animals

1. Optimization Theory as an Explanation of Matching

2. Momentary Maximization Theory

Check Your Learning 14-1

II. Theories to Explain Choice Behavior Arising from Work with Humans

A. Normative Models of Decision-Making

1. Expected Utility Theory, Subjective Expected Utility Theory, and Utilitarianism

Think Ahead 14-2

2. Probability Theory

B. Descriptive Models of Decision-Making

1. Satisficing

2. Prospect Theory

3. Regret Theory

Check Your Learning 14-2

III. Decision-Making under Uncertainty: The Role of Intuition, Heuristics, and Biases

A. The Role of Intuition in Decision-Making

Think Ahead 14-3

B. Heuristics in Decision-Making

1. The Availability Heuristic

2. The Representativeness Heuristic

3. The Recognition Heuristic

C. Unconscious Biases in Decision-Making

Check Your Learning 14-3

IV. Real Life Decision-Making: Self-Control Choices and Social Cooperation

A. How Important are Self-Control and Social-Cooperation

B. Why We Often Fail at Self-Control

1. Not Enough Experience

2. Faulty Experience (the role of superstition)

3. Delay Discounting

Think Ahead 14-4

4. Uncertainty

C. How Human Decision Making Affects the Future

Check Your Learning 14-4

Learning in the Real World: How to Quit Smoking!

Beyond Traditional Learning: Understanding Human Decision-Making

Humans, living in the insulated world of the 21st century, don’t normally make individual decisions which by themselves lead to life or death. Though of course other factors need to be considered, who you are today is in many ways a product of all of the judgments and choices you have made in your lifetime. Collectively, judgments and choices together comprise decision-making. Some of the choices you have made have been “good” choices and some have been “bad” choices. To say a choice is “good” or “bad” often refers to whether the choice leads to better outcomes at the moment (going to a party) or in the long-run (staying home and studying). However, animals living in a world of constant struggle for survival often do make choices that have an immediate affect on their lives. They need to be more concerned with surviving in the here and now rather than long-term planning. Consequently, the most important aspects of animal decision-making do not necessarily involve long-term planning, but issues of acquisition of food and mates right now. There is no cognitive ability that has a stronger evolutionary selective pressure than an ability to make a choice (see Box 14-1). The mechanisms of choice behavior seem to be very similar between animals and humans; therefore, keeping in line with the simple systems approach, we will begin our discussion with animal models of decision-making in order to better understand choice in humans, but quickly move on to human decision-making.

Box 14-1Evolution and Choice

Natural selection clearly favors organisms which can make effective choices, choices which lead to survival and reproduction. When chased by a predator, an animal must choose how to evade the predator, the penalty for unsuccessful organisms is death and a failure to contribute to the gene pool of the next generation. During a drought, an animal must choose the best strategy for obtaining water, again, the punishment for bad choices is death. In the face of uncertainty, the use of strategies and mental shortcuts (heuristics) that were effective in the past is often the best way to make affective choices. Heuristics obviously played an important role in helping humans adapt to a changing environment. The recognition heuristic (to be discussed in more detail) exemplifies this situation most clearly. If a hungry person is presented with two objects which appear to be fruit, one which they recognize and one that they don’t, the person would increase their probability of survival by choosing the fruit they recognize. If you were starving to death and you could only pick one fruit, would you choose a banana or a lychee?

______________________________________________________________________

Studying Choice in the Laboratory

Procedures for Measuring Choice in Animals and Humans

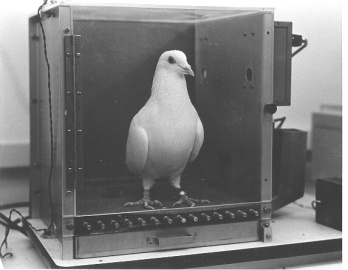

Much research with animals discussed so far implemented the use of a single choice in a Skinner box and measures such as rate of responding or latency to respond have been recorded. These types of procedures were best exemplified by the FI, VI, FR, and VR schedules. However, if a Skinner box is designed with two or more response options, then the animal’s choices and preferences can be measured. As an example, a pigeon can be presented with two keys in a Skinner box simultaneously, one red and one green. Pecking of the red key might lead to immediate access to a food hopper containing mixed grains for 2 s; pecking the green key might lead to a delay of 4 s followed by access to the food hopper for 4 s. These two options are often referred to as smaller-sooner (SS) and larger-later (LL). Researchers use this basic procedure to measure an animal’s ability to exhibit self-control (a topic we’ll return to in this chapter). Most animal researcher on choice is slow and tedious, only a single animal’s choices can be measured at any one time and it takes a long time to get an animal trained in the procedure used. But, as you might be able to guess by now, animal research takes advantage of the simple-systems approach and allows researchers to hold outside factors, such as hunger and motivation, constant.

Insert Picture 14-1 about here (Pigeon in a Skinner box)

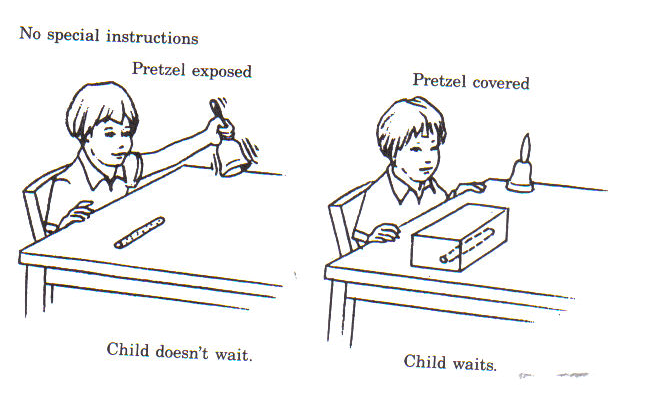

Similar choice procedures can be used with humans (though I don’t encourage the use of an actual Skinner box with humans), two or more options can be presented and the researcher can make behavioral measures such as latency to choose or percent choices for one of the options. Walter Mischel did a series of fascinating studies with children measuring preferences for marshmallows and pretzels. However, measuring choice in humans can take advantage of the power of language, and people can simply be asked for their preferences. Instead of using mixed grains as with pigeons, a procedure to measure self-control could involve asking people to choose between options. A person might be asked, “which do you prefer, $5000 that you will receive today (SS) or $10,000 that you will receive in a year”. Using hypothetical choices like this can lead to faster research which involves many more participants (hundreds or even thousands when we take advantage of the possibilities of the internet), allowing researchers to be more confident in their findings. However, in research with humans there are many more possible sources of error involved, such as motivation. If a person currently owes a loan-shark $5000, then they will almost inevitably choose the SS option in the previously described research, even if they normally would prefer the LL option.

The Matching Law as a Description of Choice Behavior

Herrnstein (1961) exposed pigeons to two different variable interval (VI) schedules simultaneously each on a separate key. If you recall, in a VI reinforcement schedule, only one response is required in order to receive reinforcement, but some amount of time must pass before a response is effective. In a VI 2 min schedule, though the exact duration between available reinforcers is not totally predictable on each trial, the durations will average 2 min though it might be 15 s on one trial and 10 min on another. However, if a pigeon pecked continually on a VI 2 min schedule, we would expect it to receive close to 30 reinforcers per hour. If given a VI 30 s schedule, we would expect the pigeon to receive about 120 reinforcers per hour. Because there were two different reinforcement schedules available simultaneously in Herrnstein’s study, the pigeons’ choices could be measured. Herrnstein looked at many different VI schedule combinations and found several things. First, if the VI schedules were the same, the pigeons spent almost exactly as much time pecking one as the other. Second, if given the choice between two VI schedules that were different, they consistently preferred (spent more time pecking) the schedule associated with the higher rate of reinforcement. But most interestingly, as seen in Figure 14-1, the percentage of time spent on a schedule almost perfectly matched the reinforcement rate from that schedule. More recent work by Grace, Bragason, & McLean (2003) that pigeons’ behaviors shift very rapidly toward this matching pattern, even when the schedules are continually changing. Herrnstein proposed the matching law to explain these results (Herrnstein, 1997). The matching law states that in a two-choice situation, the percentage of time spent on each alternative will match the percentage of reinforcers received from each alternative and is summarized by Equation 14-1. In this equation we see that the ratio of behaviors on alternative one (B1) over the total behaviors in the two choice procedure (B1 + B2) will equal the ratio of reinforcers received from alternative one (R1) over the total reinforcers received in the two choice procedure (R1 + R2). Don’t let the math scare you, all this means is that the pigeons in Herrnstein’s experiment matched effort to outcome (McDowell, 2005).

Insert Equation 14-1 about here

Insert Figure 14-1 about here

Think Ahead 14-1

****The law of gravity is often considered to be a primary law because it seems to reveal something about the nature of the universe. Do you think that the Matching Law is a law in the same sense that animal behavior always follows it?

Of course there are exceptions to the matching law (Baum, 1974). Sometimes an animal expresses an indifference to the two available choices, regardless of the schedules, then they are displaying undermatching. If the animals consistently prefer one of the options, regardless of the schedules, then they are displaying bias (I had a pigeon once with a bias for red keys, it didn’t really matter what the key led to, it always pecked the red one). Suffice it to say, despite these exceptions, the matching law does a good job describing the behavior of animals and humans in many situations. As an example, Conger and Killeen (1974) put together four members of a group and instructed them to discuss drug abuse. Three of the group members were confederates, working for the experimenters. One of the confederates had the job of keeping the conversation going. The other two confederates administered verbal “reinforcement” on VI schedules. The real participant directed the conversation toward these two confederates at a rate roughly matching the rates of reinforcement they were administering.

Theories to Explain Choice Behavior Arising from Laboratory Animals

Optimization Theory

Microeconomics studies the behavior of individual consumers as they attempt to acquire relatively scarce goods. Psychologists study operant conditioning which involves the behavior of individuals as they pursue reinforcers. If we substitute “relatively scarce goods” with “reinforcers” we find that these two methods of studying behavior are highly similar. Behavioral economics is the study of how organisms “spend” their limited resources, including time and money, it is essentially the study of how animals make choices.

The optimization theory of choice explains the matching law discovered by Herrnstein and argues that consumers will “spend” their resources in that way that will maximize their utility (Rachlin, Green, Kagel, & Battalio, 1976; Baum & Aparicio, 1999). Utility is a subjective measure used in economics to describe satisfaction or happiness. Essentially, utility arose in economic theory because everyone is different, not everyone’s satisfaction derives from money. If given the choice between $10 and a new book, some people choose the $10, some people choose the book. Presumably, those that choose the $10 receive more utility from $10 than they would receive from the book. For those that choose the book, they receive more utility than they would have if choosing the $10.

Of course, life is much more complicated than a single choice with a single outcome. If you receive a $2000 paycheck each month, you need to make some choices. Perhaps you’ll pay the bills, maybe donate some to the church, you might take a trip. Those things that you value will be different from what others value and others might spend their $2000 quite differently. Regardless of how you spend your $2000, optimization theory argues that you will maximize your utility.

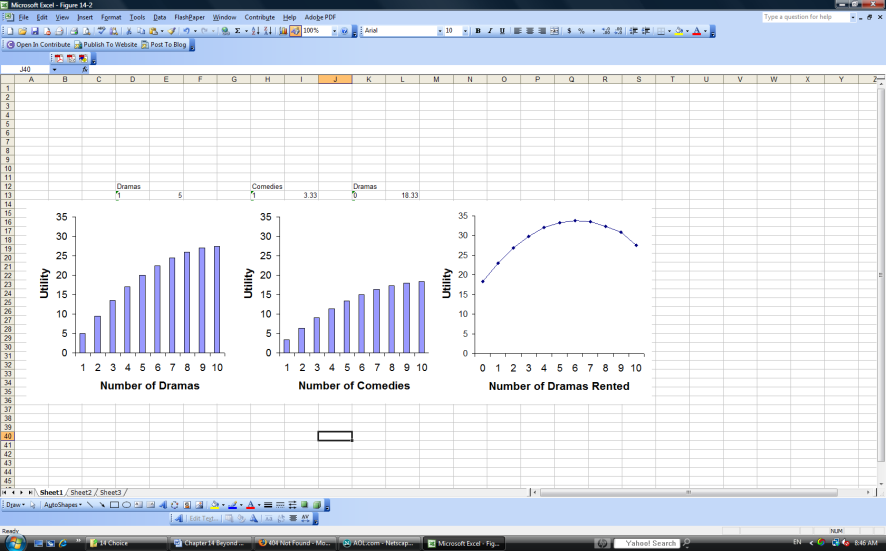

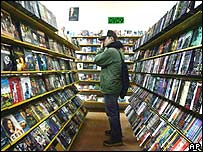

If you decide to spend a weekend having a “movie marathon” you might go to the video store and choose 10 movies for your marathon. Since you enjoy both comedies and dramas, you need to choose how many of each you will rent. Perhaps you like dramas a little more than comedies, dramas might give you more satisfaction. However, like anything, your movie viewing is subject to the law of diminishing marginal value (economic law that each additional unit of a commodity produces less value to you). The first drama you watch might lead to 5 units of utility, whereas the second drama is slightly less satisfying (4 ½ units). If you were to rent ten dramas, the tenth one might only give you ½ unit of utility. This picture can be seen in Figure 14-2a where each additional drama adds less utility than the one before. Figure 14-2b shows the value of renting comedies. Since you prefer dramas, the utility from comedies is lower at all points, but comedies are also subject to the law of diminishing marginal value. Figure 14-2c shows the utility you would receive from different combinations of comedies and dramas (since the total number of movies rented is ten, at the point where it says three dramas rented in Figure 3c implies seven comedies were rented as well). Though you prefer drama, it is the package of six dramas and four comedies that would give you the highest utility (highest point on the graph). This example seems far-fetched, after all, who has the time or ability to calculate all of that? Despite this, researchers have found repeatedly that animals and humans do in fact approach optimality in their choices.

Insert Figure 14-2 about here

Insert Picture 14-2 about here (Man in video store)

Studies of choice behavior with animals don’t use movie rentals, but instead tend to focus on those things that are important to animals, namely mating and food (Krebs & Davies, 1978). The waiting time of male dung flies at cow patties provides an excellent example of optimization (for those of you not from farm country, “patties” are cow poop). A little background is in order, female dung flies lay eggs in cow patties and prefer fresh patties to old patties. Male dung-flies search for fresh patties, then wait for females. However, the longer they wait at a patty for a female, the less “fresh” the patty becomes. A fresher patty has a better chance of attracting a female, but finding a fresh patty takes time. The male dung-fly needs to make a choice about when to move to a fresh patty. Parker (1978) calculated the ideal wait time for male dung-flies based on density of patties in a field. The male dung-flies behaved as though they somehow had access to Parker’s calculations, they waited almost exactly as long as predicted.

Insert Picture 14-3 about here (Cow patty)

Momentary Maximization Theory

Momentary maximization theory argues that organisms make choices based on which alternative is better at the moment (Shimp, 1966). Many factors will influence which alternative will lead to maximal utility at the moment including qualities of the reinforcer and deprivation of the organism. Though the momentary maximization theory and optimization theory often predict the same choices, they definitely don’t make the same predictions in all situations because the best choice in the short-run is not always the best choice in the long-run. We will return to the question of momentary maximization vs. optimization in our discussion of self-control choices.

Check Your Learning 14-1

In many ways the lives we have are a product of the choices we have made.

Studying choice behavior is relatively easy and often involves simply counting and recording behaviors.

When studying choice in humans we can take advantage of the power of language and study about not just actual choices, but hypothetical choices as well.

Research with animals and humans has discovered the matching law as a basic description of decision-making. The matching law basically states that animals will allocate their time in direct proportion to the amount of reinforcement they receive from different sources.

Optimization theory provides a link between the study of choice and evolutionary theory by describing how organisms maximally benefit from the “optimal” choices that lead to the best long-term outcomes.

Momentary maximization theory provides an explanation for decision-making that leads to the best outcome at the moment at the expense of long-term optimal solutions.

Theories of Choice Behavior Arising from Work with Humans

Normative Models of Decision–Making

Normative models of decision-making are those models of decision-making that describe the way people should make decisions. These models describe perfect decision-making by people when they have access to all information relevant to a decision, spend the time considering it all, and have the capacity to actually deal with all of the relevant information. In theory, normative models of decision-making lead to the “best” outcome every time, much like optimization theory previously described. The best option is always the one that leads to the most utility. Expected Utility Theory and Probability Theory are two of the more famous normative models of decision-making.

Expected Utility Theory, Subjective Expected Utility Theory and Utilitarianism

Expected utility theory states that when facing uncertainty, people should maximize their utility function (Baron, 2003). An example will explain this theory the best. Farmer Brown is thinking about planning crops this year, he knows some things about these crops. He knows that if the weather is perfect this year, then Crop A will yield 10 units of utility, Crop B will yield 8 units of utility, and Crop C will yield 3 units of utility. As can be seen in Figure 14-3a, if the weather is fair or poor, then he knows the utility he will receive by planting crops A, B, or C. This example incorporate decision-making under certainty and is simple (Rubinstein, 1975; Rubinstein & Pfeiffer, 1980). If Farmer Brown knows the weather will be perfect this growing season he should plant Crop A, if the weather will be fair he should plant Crop B and if the weather will be poor, he should plant Crop C. He will maximize his utility in any of these situations. Of course, we rarely have access to all of the information needed to make the best decision.

Insert Figure 14-3 about here

It seems reasonable to conclude that Farmer Brown would have access to the yields of the different crops during different growing seasons, after all, Farmer Brown is not stupid, he knows the yields for the crops for other farmers from years past in different growing seasons. However, it seems unreasonable that Farmer Brown would “know” for certain what kind of growing season he was facing. Instead, Farmer Brown would probably consult his Old Farmer’s Almanac and make some guesses about the weather for the next year. Let’s pretend that the Almanac told Farmer Brown that there was a 15% chance that the weather this growing season would be perfect, a 60% chance the weather would be fair, and a 25% chance that the weather would be poor. As can be seen in final column of Figure 14-3b, Farmer Brown would need to calculate the expected utility of each crop (for Crop A, 15%*10 + 60%*1 + 25%*-2 = 1.6) and then choose the crop with the highest expected utility. The calculation of expected utility is seen in Equation 14-2. Given these expectations for the growing Season, Farmer Brown should plant Crop B because it maximizes his expected utility this year, but it does not guarantee him the maximum output this year. If the weather is poor this year, poor Farmer Brown is going to kick himself, but this is the risk he has to take to make the “right” choice. Consequently, this situation is known as decision-making under risk (Rubinstein, 1975). Unfortunately, in many situations, we do not have access to the probabilities of the different outcomes and we need to make some guesses. Decision–making under uncertainty is the most common way we are forced to make our choices and expected utility theory falls short. As can be seen in Figure 14-3c, poor Farmer Brown is forced to make choices without enough information.

Insert Equation 14-2 about here

Subjective expected utility theory was proposed because objective probabilities of outcomes or events cannot always be determined in advance and people need to use subjective probabilities, based on their own estimations (Slovic, Fischhoff, & Lichtenstein, 1977). When forced to make decisions under uncertainty, we can make use of a decision tree as seen in Figure 14-4 to help us maximize our outcomes. Let us suppose that a juror has been sitting in the jury box listening to testimony. The juror, of course, has two choices, to convict or acquit the defendant. After hearing all of the testimony, perhaps they are 60% certain the defendant is guilty (therefore leaving a 40% chance of innocence). The juror could lay out all of the possible outcomes (there are really four, convict/guilty, convict/innocent, acquit/guilty, and acquit/innocent). The juror might give values to these outcomes based on personal judgment. The juror might believe the best outcome is acquitting an innocent person and the worst outcome is convicting an innocent person and so these two outcomes are given values of +100 and -100. The juror then assigns values for the other possible outcomes that fall between these extremes. Calculating the expected utility of each branch of the decision tree reveals that the expected utility of acquittal in this case is +10 whereas the expected utility of conviction in this case is -4. This juror, given their 60% certainty of guilt and these values for outcomes, should vote for acquittal. As a good demonstration of the generality of this theory, Shanteau and Nagy (1979) used subjective expected utility theory to predict which dating partner females would choose whereas Lynch and Cohen (1978) used subjective expected utility theory to predict helping behavior.

Insert Picture 14-4 about here (Jury in jury box)

Insert Figure 14-4 about here

Think Ahead 14-2

****Do you think that we should only consider to consequences to ourselves when making choices? Shouldn’t we also consider how our choices affect other people?

Utilitarianism, first proposed in the modern sense by Jeremy Bentham and latched onto by many social reformers such as Karl Marx, is clearly a cousin of expected utility theory. It is a theory of morality that argues that a moral choice is one that allows us to maximize utility (Bentham, 1876). The difference emerges, however, when we realize that our actions affect not only ourselves, but others as well. Stated again, utilitarianism argues that moral decisions are those that maximize utility when considering all others that are affected by the outcomes of your decision. In our modern and global world, the effects of our decisions are felt by people we have never met and, according to utilitarianism, we need to consider the impact of our decisions on their utility. This issue is coming to a head with our understanding of the affects of our behaviors on climate change where we are modifying the lives of people not only on the other side of the world, but we are modifying the lives of people that haven’t even been born yet (Ekins, 1999). Act utilitarianism argues that the individual act which would lead to the greatest good for the greatest number or the least pain for the least number should always be chosen. Rule utilitarianism argues that the best act is to follow a general rule which usually leads to the most utility. Though the differences between act and rule utilitarianism are usually little more than academic, these differences can lead to interesting discussion of moral decision-making (Emmons, 1973). If a doctor has an otherwise healthy patient come in for an appendix removal, is the doctor justified in harvesting the organs (heart and two kidneys) of this otherwise healthy patient to give to three other patients that need these organs to survive. Act utilitarianism would say yes, harvest the organs, the lives of three individuals will be saved while the only one individual will be lost. Rule utilitarianism would argue that the doctor needs to follow the general rule that usually leads to the most utility, namely, doctors do not harm patients.

Insert Picture 14-5 about here (Jeremy Bentham)

Probability Theory

Another normative model of decision-making you may already be somewhat familiar with is probability theory. Probability theory is a branch of mathematics that deals with random events and allows for the best “average” prediction to be made. Probability theory is most famously used by scientists in the form of statistics, which allow us to make decisions that are “probably” correct (Baron, 2003). Common decisions made using probability theory include the questions of whether two samples are significantly different from each other and whether or not to reject the null hypothesis. Though it is important to realize that probability theory is a normative model of decision-making, clearly the details of probability theory are far beyond this course. I will leave it to your statistics professor to explain this stuff for you!

Descriptive Models of Decision-Making

Descriptive models of decision-making are those models of decision-making that describe the way people actually do make decisions. Often, people do not have access to all of the relevant information pertaining to the decision to be made, or they are too lazy or busy to deal with it all, or they cannot handle it all. Even though descriptive models of decision-making often lead to options that are less than the best, the outcomes are usually “good enough”. Descriptive models of decision-making are cognitively cheap to utilize and we often the only types of decision-making we can use since we don’t really have access to all the relevant information anyway. Descriptive models of decision-making prevail in actual decision-making. Satisficing, Prospect Theory, and Regret Theory are three of the more common descriptive models of decision-making.

Satisficing

When I first started looking for a house, I had lots of goals. I wanted it to be close to my and my wife’s work. I wanted it to be in the best school district. I wanted it to have four bedrooms. I wanted it to be two-stories. I wanted it to be large. Oh yeah, don’t forget the price. When I started looking at houses I realized just how many there were in my urban area. Many of them had many of my desired attributes, but none had all of them. Since no house had every one of my desired properties, I needed to find a way to compare them. Ideally, I’d be able to quantify the utility each house would give me and then simply choose the one with the highest utility, perhaps through the use of a decision tree. I tried creating a spreadsheet and laying out the merits of each possible house, but it became readily obvious it wasn’t going to work. Is a three bedroom house in a good school district better or worse than a four bedroom house in a slightly worse school district? Instead, I had to decide the satisfactory level for each desired attribute. I decided that even though there were some houses that were very close to both my and my wife’s work, as long as the house was within 30 min for both of us, it was good enough. I decided the house didn’t need to be in the best school district (exemplary is the term used), as long as it was good enough (recognized). I decided that four bedrooms was an attribute I would not budge on. I decided that though I wanted a two story home, a one story home would be “good enough”. This type of decision-making exemplifies satisficing, which is an alternative to optimization proposed by Herbert Simon (1956) for cases where there are multiple and competitive objectives in which one gives up the idea of obtaining a “best” solution. When there are multiple objectives which compete with each other, the quantitative computation of the best outcome may not be possible. When satisficing, the decision maker sets minimum acceptable levels for the various objectives that would be “good enough” and then seeks a solution that will exceed these minimums. Admittedly, when satisficing it is definitely possible to miss out on a better choice, but given the limits of human cognitive capacity, we often need to settle for “good enough” (Schwartz et al., 2002; Diab, Gillespie, & Highhouse, 2008; Parker, de Bruin, & Fischoff, 2007).

Insert Picture 14-6 about here (House for sale)

Prospect Theory

Kahneman and Tversky (1979; 1984) noticed that expected utility theory was able to find the exact “right” solution every time (the one that maximized expected utility), however, they also noticed that people’s actual decisions often deviated from the ideal decisions. Prospect theory was proposed as an alternative to expected utility theory to describe how people make decisions when facing uncertainty. Kahneman was given the Nobel Prize in economics in 2002 for this work (unfortunately, Tversky died in 1996, otherwise it seems undoubted that he would have shared the award).

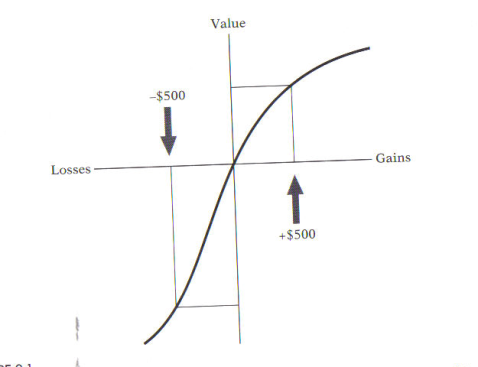

Prospect theory replaces the notion of utility with value which is figured in terms of gains and losses in relation to a reference point (Schwartz, Goldberg, & Hazen, 2008). As can be seen in Figure 14-5, the value function for gains is different from the value function for losses. The value function for gains tends to be somewhat shallow whereas the value function for losses tends to be relatively steep. The effect of this is that we tend to feel losses more heavily than gains. From a practical perspective, this means that though we might pay 50c for a candy bar, it might take 75c to convince us to sell it This discrepancy is known as the mere-ownership effect (Reb & Connolly, 2007).

Insert Figure 14-5 about here

If a question is framed in terms of gains, people’s choices are different than if the exact same question is framed in terms of losses. This is because people tend to be risk-averse for gains, but risk seeking for losses. Take the following as an example of risk-aversion for losses: “To illustrate risk aversion …, consider the choice between a prospect that offers an 85% chance to win $1000 (with a 15% chance to win nothing) and the alternative of receiving $800 for sure. A large majority of people prefer the sure thing over the gamble, although the gamble has higher (mathematical) expectation.” (Kahneman & Tversky, 1985, p. 341). If this same gamble is framed in terms of losses, people tend to be risk-seeking: “Consider, for example, a situation in which an individual is forced to choose between an 85% chance to lose $1,000 (with a 15% chance to lose nothing) and a sure loss of $800. A large majority of people express a preference for the gamble over the sure loss. This is a risk seeking choice because the expectation of the gamble (—$850) is inferior to the expectation of the sure loss (—$800)” (p. 342). The differences in our choices comes simply from the shape of our value function as seen Figure 14-5.

Regret Theory

Another alternative that tries to explain deviations from the choices predicted by expected utility theory is regret theory (Loomes & Sugden, 1982). Just like prospect theory, regret theory explains why people tend to be risk averse in some situations but risk seeking in others. Regret theory assumes that people sometimes experience feelings of regret after making choices and these feelings of regret are undesirable. People take these feelings of regret into account when making choices and try to avoid them. As described previously, people tend to display risk aversion for a positive gamble: when asked to choose either $800 for sure or an 85% chance at $1000 most people choose the $800 for sure. Regret theory argues that this choice is made in order to avoid the possible regret we would feel if we chose the probabilistic option and lost. People tend to be risk seeking when it comes to losses: when asked to choose between an 85% chance of a loss of $1000 or a sure loss of $800, people tend to choose the gamble. Regret theory argues we seek this risk to avoid the regret we would feel if we picked the sure loss, we would regret not taking the gamble because we could have lost $0 (Plous, 1993; Marcato & Ferrante, 2008).

Check Your Learning 14-2

Theories of choice arising from work with humans can be categorized as either normative (explaining how we should decide) or descriptive (explaining how we actually do decide).

Expected utility theory, arising from economics, is the decision-making strategy that leads to the best outcomes.

Utilitarianism, an extension of expected utility theory, reminds us that we need to consider the consequences of our choices not only as they affect us, but as they affect others as well.

In most decision-making situations there is a degree of probability and uncertainty.

Because of uncertainty, humans seem to fall back on strategies such as satisficing and regret avoidance when making choices.

Decision-Making under Uncertainty: The Role of Intuition, Heuristics, and Biases

As we’ve seen already, most of our choices are made under conditions of uncertainty. In some cases we don’t have access to the probabilities of the different outcomes; in other cases we don’t really know how much utility the different outcomes would give us. Even if we do have all of the information and we technically have a situation that is decision-making under certainty, the number of competing options may be so large that we can’t accurately compute utility. Because so much of real-life decision-making is so complicated, we tend to fall back on shortcuts such as intuition and heuristics to help us make decisions and form judgments.

The Role of Intuition in Decision-Making

Intuition is a type of thinking that involves understanding that is quick and effortless and often involves insight (Myers, 2002; Price & Norman 2008). Generally, people cannot verbalize the thought processes that are active when they are thinking intuitively. Prince Charles, in the 2000 BBC Reith lecture, summed up intuition with the following:

Buried deep within each and every one of us there is an instinctive, heart felt awareness that provides—if we allow it to—the most reliable guide as to whether or not our actions are really in the long term interests of our planet and all the life it supports. . . . Wisdom, empathy and compassion have no place in the empirical world yet traditional wisdoms would ask ‘without them are we truly human?‘

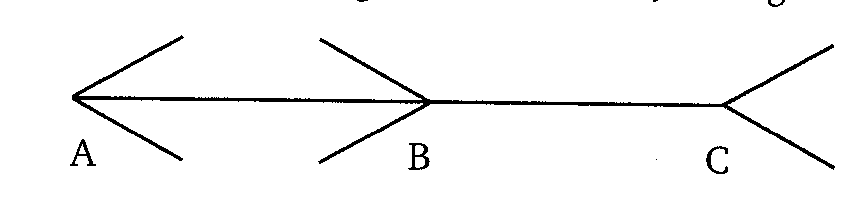

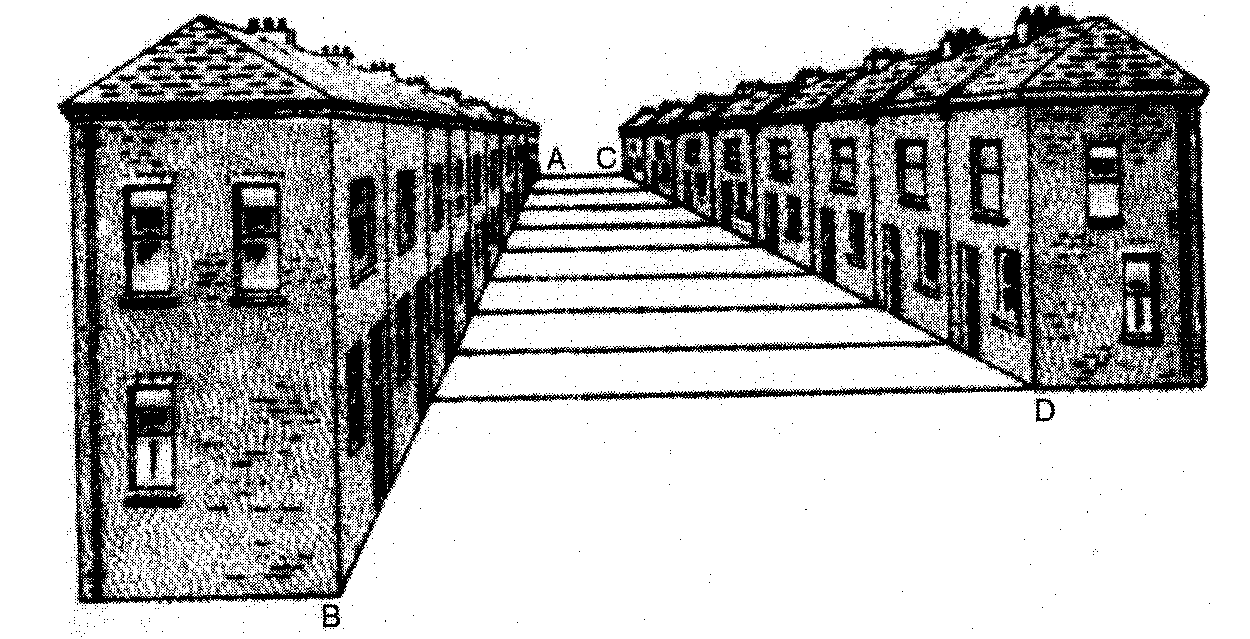

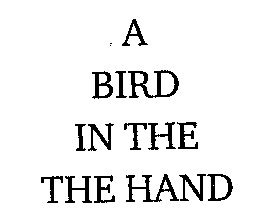

There are many headline stories about the successes of intuitive thinking (they almost always begin with “I could just sense that something was wrong…). Unfortunately, as seen in Figure 14-6, our intuitions also often fail us and lead us to misjudgments.

Think Ahead 14-3

****If intuition can lead to such stunning failures in thinking, why would we possibly use it instead of cold, logical, and rational thought?

Because we are required to make thousands of decisions daily (when should I breathe and blink, what should I wear, should I stop at the orange light, is the person I’m talking to genuinely happy or faking it, etc) and if we thought logically and rationally about every judgment and choice we make, we would have no time left for anything else. Decision-making seems to be made on a dual track system, at one level intuitive and effortless, at another level conscious and effortful. Some decisions have immense consequences and therefore deserve deep thought, you should probably not use intuition to decide your college major. However, intuitive decision-making releases us from the burden of the thousands of daily decisions which need to be made quickly or whose consequences are minimal. That is, intuition is cognitively cheap (Acker, 2008).

Insert Figure 14-6 about here

Even though intuition seems to involve no conscious thinking, there is ample evidence that intuitive thinking can really only occur once one has mastered a skill (Rieskamp, 2008; Goodie & Young, 2007). To master a skill and become an expert in something one must practice for a long time. Experts tend to view problems in a different way from novices. As an example, an expert in English grammar (often a native speaker) usually knows the right answer but cannot verbalize why it is the right answer. A novice in English grammar (someone learning English) tends to make more mistakes than an expert, takes longer to make decisions, and often makes decisions based on rules that can be verbalized (Reber, 1989). Likewise, Klein (1997) reports about the decision-making processes of both novice and expert firefighters. When put in training scenarios, novice firefighters make far more mistakes than experts. When the expert firefighters were asked to verbalize why they made the choices they made, they commonly report that they did not make any decisions, they just “saw” what needed to be done and did it. Clearly, the experts relied on intuition in their decision-making (Zsambok & Klein, 1997).

Heuristics in Decision-Making

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that help decision makers make choices and form judgments in the face of uncertainty. Heuristics contrast with algorithms. Algorithms are methodical rules which guarantee that a problem will be solved. If you wanted to trace a maze to find the solution, you could use an algorithm which involved rules that would guarantee success. Perhaps the rule set would look like the following:

1. Go left at all choice points if possible.

2. If striking a dead end, backtrack to a choice point.

3. If left turn has previously been chosen, turn right.

If this algorithm sounds cold and methodical, be comforted in knowing that this is the way computers solve problems, but is generally not the way humans do. A human would probably solve the maze using a heuristic, perhaps working simultaneously from the front and back of the maze, trying to make the ends meet. Like intuition, heuristics often lead to faster judgments and decisions (Gigerenzer & Goldstein, 1996). Unfortunately, like intuition, heuristics often lead to errors in thinking. We will consider three of the more famous heuristics in detail, the availability heuristic, the representativeness heuristic, and the recognition heuristic.

The Availability Heuristic

The availability heuristic is a mental shortcut used to help us judge the probability of some event (Tversky & Kahneman, 1982b). Basically, if an event is readily available in our minds, then we assume it occurs often. Generally, this is a good strategy to follow because the things that occur the most frequently are the things we have experienced the most. Going back to Aristotle’s laws of association, the more frequently we experience an event, the stronger the memory for that event. If asked to think of a bird, the image that will come to mind (be available) will probably be the type of bird you have seen the most times, a bird which is common where you are from (for me it’s a robin). Of course, there are other reasons things come readily to mind other than the frequency of their occurrence. Tversky and Kahneman’s (1973) most famous example of the errors in judgment the availability heuristic can lead to involved the following question: “In a typical sample of text in the English language, is it more likely that a word starts with the letter K or that K is its third letter (not counting words with less than three letters)?” (p 211). Most people believe it is more common to have K as the first letter but in fact, there are twice as many words that have K in the third position. Why would this error in judgment occur? Because we have experience with alphabetizing things and we alphabetize using the first letter, not the third. We have more “experience” with K in the first position and therefore, words starting with K are more available to our memory.

The advent of constant access to the news and entertainment on cable television networks, the radio and the internet has led to a hypervigilance toward world events. Airplane crashes have not become more common, in fact, they have dropped 65% in the ten year period ending in 2007 and this period even encompassed the tragedy of 2001 (Wald, 2007). However, when airplane crashes do occur, the news reports them endlessly, thus making crashes come readily to mind. Fear of flying is at an all time high. However, just as with the commonness of words with the letter K as the first letter, the availability of airplane crashes in our memory does not equate with their frequency. Just like words with K in the third position, we tend not to see all the airplanes that do not crash.

Insert Picture 14-7 about here (Airplane)

The Representativeness Heuristic

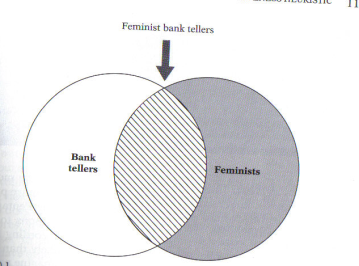

As a demonstration of the role the representativeness heuristic plays in judgment formation, Tversky and Kahneman (1982) provided participants with the following:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in antinuclear demonstrations. Please check off the most likely alternative:

_____ Linda is a bank teller.

_____ Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

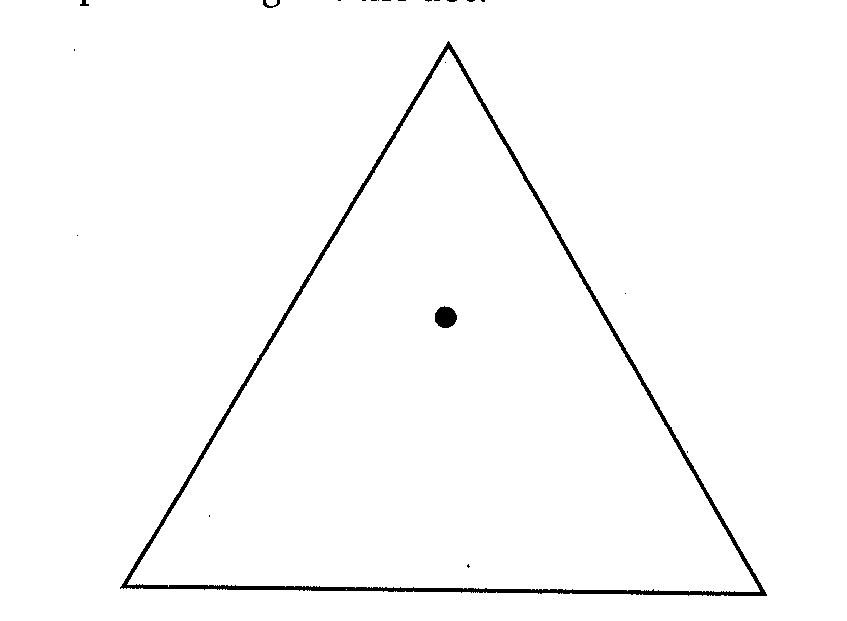

Nearly everyone believed that Linda was a feminist bank teller. However, as seen in Figure 14-7, it must be more likely that Linda is simply a bank teller (a larger group) than a feminist bank teller (a smaller group). When using the representativeness, people judge the membership of people or objects into categories based on how well the person or object represents the “average” member of the category. In this case, the description of Linda seems somewhat representative of people that belong to the category of feminists. Because Linda seems to represent the category, she must be a member of that category. “As the amount of detail in a scenario increases, its probability can only decrease steadily, but its representativeness and hence its apparent likelihood may increase (p. 98).” The implications for this become readily obvious in the following: Which would a jury be more likely to believe, “He fled the scene of the crime” or “He fled the scene of the crime because he was feeling guilty”? Which one is more likely to be true?

Insert Figure 14-7 about here

Insert Picture 14-8 about here (Bank teller)

The Recognition Heuristic

The recognition heuristic is a mental shortcut whereby we tend to prefer those things with which we are familiar (Goldstein & Gigerenzer, 2002). A focus group was used to tell the makers of the headache product HeadOn which type of commercial would most effectively sell their product. Turns out the most effective commercial involved repeating the name of the product over and over and over. I had always wondered why a company like McDonalds would continue to spend such a large portion of their budget on advertising, but an understanding of the recognition heuristic should make it obvious. When children are presented with French fries or chicken nuggets in McDonald’s wrappers or plain wrappers, the kids clearly preferred the ones in the McDonalds wrappers despite being the exact same product (Robinson, Borzekowski, Matheson, & Kraemer, 2007).

Insert Picture 14-9 about here (McDonald’s arches)

In the movie The Distinguished Gentleman, a conman played by Eddie Murphy who had the same name as a recently deceased long-time senator got his name on the ballot. His campaign slogan was “Jeff Johnson, the name you know.” Since he had no political experience at all, he should have lost resoundingly, instead, he won. Though this seems far fetched, voting for what you are familiar with certainly takes far less effort than doing the homework to learn about each of the candidates.

Insert box 14-1 here (Evolution and Choice)

Unconscious Biases in Decision–Making

As previously described, thinking seems to proceed on a dual track system. On the conscious level thinking is planned, on the unconscious level thinking is automatic. Automatic thinking is done to relieve the conscious mind of all the tedious judgments and choices that need to be made and usually the automatic thinking does a good job. However, some unconscious biases can slip in. Though everyone seems to use these biases, some seem more susceptible to their influence than others. McElroy and Dowd (2007) examined one personality factor, openness-to-experience, which sees to make people more likely to fall back on at least one of the biases when making judgments. Additionally, some biases are so unconscious they don’t even seem to make sense, Simonsohn (2007) reports in his study Clouds Make Nerds Look Good that during the university admission process, rates of admission rise 11% on cloudy days. An understanding of the most notorious of these biases can help us become better thinkers. We will examine anchoring, framing, and overconfidence, but others exist as well such as the hindsight bias (Fischoff & Beyth, 1975) and the gambler’s fallacy (Sundali & Croson, 2006).

One common bias we use when forming judgments is called anchoring. When we are presented with the need to form a judgment, we often start with an implicitly suggested reference point (the “anchor”) and make adjustments to it to reach our estimate. When asked to quickly estimate the product of 1 X 2 X 3 X 4 X 5 X 6 X 7 X 8, people’s average guess is 512. When asked to estimate the product of 8 X 7 X 6 X 5 X 4 X 3 X 2 X 1, people’s average guess is 2,250 (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Apparently people are really bad at this task in either case, the actual answer is 40,320. However, the main point is that when the question started with a small number (1) the estimate was much lower than when the question started with a large number (8). People seem to anchor on the first number they see when forming their judgment. In a study of the effects of anchoring on real estate prices, Northcraft and Neale (1987) presented the same house to four different groups of realtors with the only difference being the listing price presented on the sheet containing the specifications. As seen in Table 14-1, the realtors were asked to estimate the appraised value, and suggest a recommended selling price and the lowest offer that should be taken for the home. Afterwards, the realtors were asked to describe which factors they used in their judgments, none of them stated that the listing price of the specification sheet was a factor. However, since this was the only difference, the realtors most certainly must have used the listing price as an anchor point from which to begin their judgments since increases in the listing price are clearly related to increases in their judgments.

Insert Table 14-1 about here

Framing refers to the way a question is asked or an alternative is presented. The framing of an alternative or question can bias judgments and choices considerably. Ground round is the best class of meat for making hamburgers that is generally available. The butcher can charge more for this premium meat which is usually packaged as 90% lean. However, what if the package said 10% fat, would the butcher sell as much? Harris (1973) presented participants with a movie, then asked half of them “How long was the movie?” and the other half were asked “How short was the movie?” After seeing the exact same movie, those presented with the first question judged the movie to be 130 min long whereas those presented with the second question judged the movie to be 100 min long. Similarly, after being presented a basketball player, some were asked “How tall was the basketball player?” while some were asked “How short was the basketball player?” Estimates were 79 in. and 69 in. respectively. Clearly this is a bias which can be used by lawyers to quickly and easily get the answers they are looking for.

Confidence is generally a good thing; it gives us motivation and makes us persist at tasks. Unfortunately, we tend to have overconfidence in our judgments of what we know creating an unconscious bias. When drivers are asked, 82% respond that they are in the top 30% of safe drivers. Sixty-eight percent of lawyers in civil cases think their side will win the case. When Harvard business school students were asked, 86% said they were better looking than their classmates. Though these examples of overconfidence might be of benefit to the individual, other cases clearly are not. When spouses argue, usually both are absolutely confident they are right and their spouse is wrong. In most wars, both sides are confident that theirs is not only the right moral position, but also they are confident that their side will prevail.

Check Your Learning 14-3

When making decisions in the face of uncertainty we often make choices without really knowing why we made them. Sometimes, we use our intuitions, or gut feeling, when choosing. Other times we fall back on heuristics which are mental shortcuts that simplify the decision-making process and usually lead to the correct choices.

Heuristics allow us to make decisions in situations where we can’t even verbalize the choice situation.

Our judgments are often influenced by unconscious biases.

Though heuristics and biases usually operate unconsciously and lead to better choices, sometimes they do not. Many notorious examples exist of bad choices that have arisen as a result of heuristics and biases.

Real Life Decision-Making: Self-Control Choices and Social-Cooperation

Most decisions we make are between two choices. Usually one of these choices is easier or more fun at the moment, perhaps even illegal or immoral. The other choice is usually harder or less fun at the moment. Ironically, the easy and fun choice tends to lead to bad outcomes in the long-run whereas the hard choice tends to lead to good long-term outcomes. Self-control refers to the control of behavior using internal controls (such as diligence or morality) rather than external controls (such as rules and laws). Behaviorally, one is said to exhibit self-control when they choose that thing which is harder at the moment and bypass the easier thing. Self-controlled choices tend to lead to optimization. Similarly, one is said to exhibit impulsiveness if they choose the thing that is easier or more fun at the moment. Examples of self-control choices abound in our lives. A student that has a test in the morning that chooses to stay home and study is exhibiting self-control. A classmate in the same situation that instead chooses to go to a party is exhibiting impulsiveness (Rachlin, 1974; 1991; 2000). However, these self-control and impulsive choices are really part of a larger pattern of behavior which leads to desirable or undesirable consequences (Rachlin, 1995). Another way to think of self control is: “… is a conflict between particular acts such as eating a caloric dessert, taking an alcoholic drink, or getting high on drugs, and abstract patterns of acts strung out in time such as living a healthy life, functioning in a family, or getting along with friends and relatives.” (Brown & Rachlin, 1999, p. 65)

Brown and Rachlin (1999. p. 65-66) describe self-controlled decision-making in slightly different terms: “In formal terms, suppose two alternative activities are available, a relatively brief activity lasting t units of time, and a longer activity lasting T units of time, where T=nt and n is a positive number greater than one. In other words, the duration of t is less than that of T, and n of the smaller t’s fit into a single T. The ambivalence inherent in a self-control problem depends on two conditions:

1. The whole longer activity is preferred to n repetitions of the brief activity, and

2. The brief activity is preferred to any t-length fraction of the longer activity.”

The alcoholic might prefer a lifetime of sobriety (T) over a lifetime of drunkenness (nt). The only way to truly achieve the sobriety they prefer is the repeated choice of sobriety, day after day after day. The problem of addiction arises because one night of drunkenness always beats one night of sobriety. These situations involving self-control choices are ones in which the consequences of our choices fall to ourselves, sometimes the consequences of our decisions fall to others.

In situations where the consequences of our actions fall to others, there is again usually two basic choices, one easy (often illegal or immoral as well) and one hard. We exhibit selfishness when we make the choices that are easy for us because they tend to have consequences that are bad for others. Social-cooperation is exhibited when we make choices that are hard because they usually have consequences that are good for others (Rachlin, 2002). Some simple examples might involve littering or speeding. When I was stopped at a red light the other day I witnessed a classic case of selfishness. The person in the car next to me unrolled their window a crack, and then threw their trash out the window. Then, when the light turned green, they took off in their car like a bat out of hell, completely disregarding the safety of others. Both of these behaviors are considered to be selfish because they are acts which are beneficial to the individual (they now have a clean car and got to their destination sooner) and society suffers the consequences (the roads are a little more dirty and unsafe than they were before).

The tragedy of the commons is a formalization of the problem inherent in the conflict between social-cooperation and selfishness. In situations where collective resources are shared by a group of people (such as common grazing areas for shepherds), it is in people’s inherent best interest to try to exploit as much of the resources as possible. Overgrazing and overfishing are the common outcomes when there are shared resources. It is in a fisher’s selfish best interest to catch as many fish as possible (make more money), but it is in the collective best interest for each fisher to limit their catch such that the group together only harvests a sustainable level of fish. Unfortunately, if no external controls such as legal limits are in place, the result usually is a “tragedy” involving dead fishing waters where none of the fishers can catch anything. A classic view of conflict states that everyone working in their own selfish best interest create an outcome that no one wants, whether this conflict be fishing, grazing, or nuclear arms races. Brown and Rachlin (1999, p. 66) conclude: “The social cooperation problem may be formalized in the same way as the self-control problem: two alternative activities are available; one maximally benefits an individual person, p; the other maximally benefits the group, P=np.”

The problem of self-control can be considered a special form of the social-cooperation problem. In the social-cooperation problem, acts which benefit the self tend to exact a cost against the collective group of others. In the self-control problem, acts which benefit the ourselves today tend to exact a cost to all of our future selves.

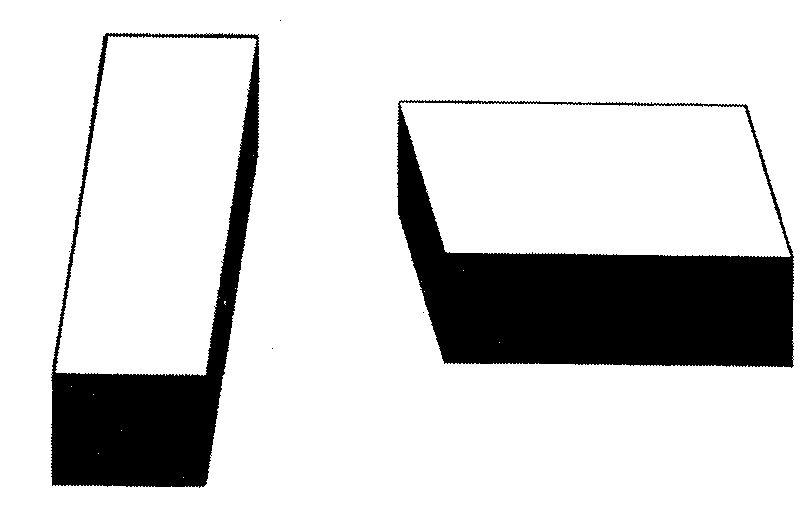

How Important are Self-Control and Social-Cooperation

The ability to make self-controlled choices is probably the most important skill one can achieve in their lives and the greatest gift we can teach our children. Mischel and Baker (1975) exposed preschool children to a delay of gratification task (a measure of self-control). Children were given a pretzel-rod and a bell (see Figure 14-8). The experimenters then told the children they were going to leave the room for some time. If the children wanted to eat the pretzel, all they had to do was ring the bell and the experimenter would return immediately and the child would be able to eat the pretzel. However, if the children could wait until the experimenter returned, they could have a marshmallow (a more preferred reward). There was considerable variability in the children’s ability to wait for the preferred reward. Mischel, Shoda, and Peakes (1988) followed up with these children as adolescents. Children that had been better able to wait for a marshmallow as preschoolers were rated as more academically and socially competent as adolescents. There was even a correlation between ability to wait as a preschooler and SAT scores taken in high school. Though controversial, SAT scores are correlated with college grades and college grades are correlated with various measures of job success. Ultimately, ability to wait for a marshmallow while a preschooler is correlated with success in life. This definitely sounds like something I need to teach my children!

Insert Figure 14-8 about here

Success in life always requires us to bypass momentary pleasures. If you want to be financially successful (rich!) you must bypass the pleasures that spending your money right now could provide (a yummy cheeseburger perhaps) and instead invest it for a larger return in the long-run. If you want to be spiritually successful you must bypass the pleasures you could receive on Sunday morning by sleeping in and instead go to church regularly. If you want to be successful in college, you must bypass the short-term pleasures you could receive by going to parties or watching television and instead spend the time studying. If you want to be…alright you get the idea, ALL individual success comes through repeated self-controlled choices (Rachlin, 2000). Though some of us are better than others at making self-controlled choices, all of us fall short of our full potential when we occasionally make impulsive choices. However, if you have made it this far in the text, then you are probably pretty good at bypassing pleasures (I’m sure you can imagine something you could be doing right now that would lead to more gratification than reading this text!).

Ultimately, all success that a society has comes from social-cooperation. As described previously, when people are given the ability to choose between selfishness and social-cooperation, the “natural” outcome is a tragedy that no one wants and if each individual is given the opportunity to choose freely, the collapse of civilization seems the inevitable outcome (Rachlin, Brown, & Baker, 2000; Brown & Rachlin, 1999). However, this seems a bit extreme because there are both internal and external controls in place which keep selfishness in check and ensure the success of society. Ideally, as children grow up they gain a sense of morality which invokes a feeling of guilt in them when they deviate from the good of others and act selfishly (Freud refers to this as the Superego). The great Christian writer C. S. Lewis (1952) describes a Universal Human Morality or Natural Law which is shared by everyone. I don’t murder and steal because I feel in my gut that these behaviors are simply wrong. However, this internal control isn’t perfect (and seems to be almost totally absent in a few individuals such as those with antisocial personality disorder which used to be referred to as moral insanity); I can choose to ignore this Natural Law, therefore external controls are also in place. External controls such as laws and mores force people to choose social-cooperation. A small fraction of individuals refrain from murdering and stealing, not because they believe these behaviors are wrong, but because they are afraid of being caught and sent to jail.

Why We Often Fail at Self-Control

Often, when we are making bad choices (choosing impulsively), we know we are making bad choices but we do it anyway, why? Though occasionally we make bad choices because we don’t understand the consequences, often we know perfectly well what the consequences of our choices are, but choose to ignore them.

Failure to Understand the Consequences

The outcomes of impulsive choices tend to feel good now whereas the outcomes of self-controlled choices tend to feel bad now. When given the choice, the dieter clearly knows that dessert is going to taste and feel good now, whereas skipping dessert is not going to be fun. Even a baby knows that dessert tastes good; jars of Gerber desserts are much easier to feed a baby than jars of Gerber strained peas. However, the long-term consequences of dessert eating are less clear and need to be learned. It is only through experience that we know that skipping dessert tends to lead to weight loss and eating dessert leads to weight gain. It is well established that ability to make wise choices increases with age and experience (Levin, Weller, Pederson, & Harshman, 2007). One of the reasons we fail to make self-controlled choices is that we do not yet have enough experience to know the long-term consequences of our choices.

However, a dieter does not need to learn the long-term outcomes of dessert eating exclusively from their own experiences. We can also learn, through the process of social learning, about the long-term consequences of our choices by seeing what happens to others. In college I had a dorm mate that made bad choices (sleeping in, partying, etc) and really quickly failed out of school. I was able to learn from the experience, I concluded that if I made the same types of choices, I too would probably suffer the same fate. I was able to anticipate the probable long-term consequences of a series of choices without having experienced the consequences myself. This is the way social learning is supposed to work. However, I remember a television program called Beverly Hills 90210 which featured a bunch of spoiled high school kids with silly problems. As the show progressed, the kids got too old for high school so they all “graduated”. Almost all of them went to an elite university (the fictitious California University). The funny part was, during the years the program revolved around high school, we never saw those kids studying, we only saw them out having fun and having personal crises. What lesson might a naïve person pull from this? Partying and having fun is the way to get admitted to a good university! If anyone really believed this, then it could definitely explain at least some of the bad choices we make. In a more believable way, advertising’s job is to make us fail to understand the consequences of our choices. Beer commercials always feature people having fun, never the hangovers or the severe consequences of alcohol addiction.

Delay Discounting

Another common reason we fail to exhibit self-control is delay discounting. Quite simply, a promise of $20 which you are to receive today is more valuable than a promise of $20 which you are to receive in a year (Rachlin, 1991). The value of the $20 is discounted (lost) when its receipt is delayed. Though the exact formula for the discount function is subject to debate (Brown, 2000; Myerson & Green, 1995; Rachlin, 2006), the general properties of delay discounting function are not. As the delay to the receipt of a reinforcer increases, the perceived value of that reinforcer decreases. Rachlin used the properties of the discount function to help describe why people gamble even in the face of heavy losses (Rachlin, 1990; Rachlin, Siegel, & Cross, 1994). A separate, but similar, function exists for probability discounting (Rachlin, Brown, & Cross, 2000; Rachlin, 2006). Many bad decisions, such as the unsuccessful dieter, can be explained using discounting.

The person trying to lose weight is faced with the following dilemma, eating dessert feels good right now whereas not eating dessert feels bad right now. Because these consequences are immediate, their values are not discounted. However, the long-term consequences of eating dessert are bad whereas the long-term consequences of not eating dessert are good. The values of these long-term consequences, since they are delayed in time, are discounted. Even though the long-term consequences of eating dessert include weight gain, the very thing the dieter is trying to avoid, the weight gain doesn’t occur until some distant point in the future, a point which is hard to see and therefore has little impact on decision-making today. As can be seen in Figure 14-9, the value of dessert right now appears to be more valuable than weight loss due to the immediacy of the dessert.

Insert Figure 14-9 about here

An understanding of the nature of the discount functions gives us a few important tools for increasing self-controlled choices (Rachlin, 2000).

Think Ahead 14-4

****How might a person on a diet take advantage of their knowledge of the discount function to help them lose weight?

If the dieter were to make the choice about whether or not to eat dessert in the morning rather than at the moment the dessert cart arrives, they would inevitably choose to skip dessert. This is because at the farthest left point in Figure 14-10 (labeled morning) the value of losing weight exceeds the value of dessert. When the choice is made far enough away in time, the dieter can “see” the right choice. Unfortunately, if allowed to switch choices, the dieter will often choose dessert when the time comes because its value is higher at that point in time (labeled dessert time). However, if the dieter can make a precommitment to skipping dessert in the morning, that is, if they can make a situation whereby their ability to switch choices is removed, they will often be successful at skipping dessert. Perhaps they could only bring enough money to the restaurant to afford dinner, or they could tell their dinner companion to stop them from choosing dessert.

Insert Figure 14-10 about here

Uncertainty of Consequences

The consequences of our actions, especially the long-term consequences, are uncertain (Brown & Rachlin, 1999; Brown & Lovett, 2001). When participants in Brown’s (2006) experiment were asked for the probabilities of events they experienced during an experiment, the most common response given was 50%, indicating that they believe it was a random process, despite the fact that in actuality the event occurred 85% of the time. People have an unfortunate tendency to equate a probability they don’t understand with randomness and unpredictableness. Though uncertain, 85% is clearly not unpredictable. Though the long-term consequences of our decisions is often probabilistic, that does mean they are either random or unpredictable. If it were possible to know that smoking was guaranteed to give you lung cancer and make you die a painful death, no one would smoke. This is not how the world works. Instead, the probability of getting lung cancer and dying a painful death increases if you smoke and decreases if you don’t smoke. This uncertainty makes self-controlled decision-making even harder. The smoker that is contemplating quitting might say, “My great aunt Ruth smoked 3 packs a day and she lived to be 109!” or “My cousin Bob quit smoking, but then got hit by a bus the next day.” Even though the truth is that smoking increases the probability of lung cancer, these vivid cases are in some ways more convincing (especially to the smoker that is looking for justification anyway).

How Human Decision Making Affects the Future

In times of environmental stability, animals generally benefit through optimization (self-control) while in times of environmental instability, momentary maximization (impulsiveness) seems to be the best strategy. Studies of animal choice tend to reveal that impulsiveness dominates (Brown, 2000). Humans on the other hand, tend to be better at making self-controlled choices. Though almost all animals have evolved behaviors which allow them to live together in groups, as described in Chapter 10 (Comparative Cognition) the mirror neuron system combined with language abilities seems to have given humans a leg up on the evolutionary ladder allowing for levels of self-control and social-cooperation not possible with other animals. So though the ability to make effective choices has been heavily selected in all animals, it seems to be particularly true in humans. Admittedly, humans tend to be selfish and impulsive at times but language abilities allow them to benefit from the experiences of others, thus allowing us to understand the long-term consequences of our actions in ways other animals could never possibly do. This clearly makes self-control and social-cooperation the dominant decision-making options. However, since we are less than perfect, external controls have been put in place to ensure a harmonious society.

There has been a new understanding in recent years of the long-term consequences of our choices on other people, both those currently alive and those not even born yet. This global level thinking which is epitomized by the green movement is encouraging. Though it is easy to watch the news which tends to feature the consequences of bad choices people have made, the new style of thinking which is coming to dominate gives me hope. Maybe we as a society can put aside our individual selfishness and truly work together, making the hard choices that benefit us all.

Check Your Learning 14-4

The decisions we make regularly often consist of two choices, one easy and one difficult.

Generally, those choices that are easy at the moment are bad in the long-run and those that are hard at the moment are good in the long-run.

In the self-control problem the consequences of our choices fall to ourselves and we maximally benefit in the long-run by making the hard choices.

In the social-cooperation problem the consequences of our choices fall to others and society maximally benefits in the long- run when each individual makes the choice which is hard at the moment.

Despite a variety of internal and external controls on behavior, we often fail and make the choice which is easy at the moment.

We make the easy choice for a variety of reasons including a failure to understand the consequences of our decisions, discounting of delayed outcomes, and a lack of understanding of the uncertainty inherent in any choice situation.

Learning in the Real World: How to Quit Smoking!

We can use our understanding of the curve in Figure 14-8 to help us enhance our self-control. If you are trying to quit smoking, then Figure 14-8 could be modified so that the shorter bar represents the value of smoking a cigarette whereas the taller bar represents the value of good health, the difficulty in making the right choice remains the same. However, if one could somehow lower the value of smoking or raise the value of not smoking, the story would be different. When I was quitting smoking, this is exactly what I did. To raise the value of not smoking, I gave myself an extra reward. Any day that I didn’t smoke, I allowed myself to buy any candy I wanted (one of my other vices). However, lowering the value of smoking was a more difficult task. I was living in Pittsburgh, PA at this time and it was February, definitely not a good time to be a smoker that is stuck outside. I made sure to watch all the smokers huddled outside my building and told myself that was what I had looked like when I smoked, not very bright looking. This effectively took away some of the value of smoking. I was able to raise the value of not smoking a little bit and lower the value of smoking a little bit; it was enough that the value of smoking at the moment was lower than the value of not smoking at the moment, I quit!

Key Terms

Act Utilitarianism: Approach to utilitarianism that argues that each time a decision is made, the act which leads to the greatest good for the greatest number should always be performed.

Algorithm: A methodical rule that guarantees that a problem will be solved.

Anchoring: A bias in decision-making whereby our judgments are influenced by a reference point which is given.

Availability Heuristic: A mental shortcut which makes us believe that things that come easily to mind occur more often than things that do not come easily to mind.

Behavioral Economics: The study of how organisms allocate their limited resources, including time and money.

Bias: A deviation from matching in which an animal consistently prefers one alternative in a two choice procedure, regardless of the outcomes of the alternatives.

Choice: A form of decision-making which involves selecting among competing alternatives.

Decision-Making: General term which incorporates choice among alternatives and judgment formation.

Decision–Making Under Certainty: Decisions made in which the factors that determine the outcomes of the different choice alternatives are known with certainty.

Decision-Making Under Risk: Decisions made in which the factors that determine the outcomes of the different choice alternatives occur with known probabilities.

Decision-Making Under Uncertainty: Decisions made in which the probabilities of the different factors which affect the outcomes of the different choices are uncertain.

Decision Tree: A graph used to guide decision-making which shows all possible choices and all possible outcomes.

Delay Discounting: The loss in value of a reinforcer due to a delay in its receipt.

Descriptive Models of Decision-Making: Those models of decision-making that address how humans actually make decisions. Include prospect theory, Satisficing, and regret theory.

Expected Utility: Calculated by multiplying the probability of an outcome times the value of the outcome. With multiple possible outcomes, this calculation must be completed multiple times and the resulting products added together.

Expected Utility Theory: When facing uncertainty, people should behave as if they were maximizing the utility function of the possible outcomes.

Framing: A bias in decision-making whereby our decisions are influenced by the way a question is asked or a choice is presented.

Heuristics: Mental shortcuts that help decision makers make judgments and choices in the face of uncertainty.

Impulsiveness: The choice for things which are easier at the moment. Related to momentary maximization.

Intuition: Type of thinking that involves understanding that is quick and effortless and often involves insight.

Judgment Formation: Type of decision-making in which one estimates the likelihood of an event.

Matching Law: In a two-choice situation, the percentage of time spent on each alternative will match the percentage of reinforcers received from each alternative.

Momentary Maximization Theory: Theory of choice that argues that organisms make choices to maximize their satisfaction (utility) at the present moment.

Normative Models of Decision-Making: Those models of decision-making that address how humans should make decisions. Include expected utility theory and probability theory.

Optimization Theory: Theory of choice behavior which assumes that consumers spend their resources in the way that maximizes their utility.

Overconfidence: A bias in decision-making whereby we are more confident than correct, an overestimation of the accuracy of one’s beliefs and judgments.

Precommitment: Situation where the individual makes a decision well before the actual time where consequences would be given and removes the ability to switch choices later.

Probability Theory: A branch of mathematics that deals with random events and allows for the best “average” prediction to be made.

Prospect Theory: Descriptive theory of choice under risk. Developed to account for differences between the ideal perfect choices predicted by expected utility theory and the way people really make choices.

Recognition Heuristic: A mental shortcut that biases us towards choosing those things that are familiar to us.

Regret Theory: Descriptive model of decision-making that assumes that decision makers experience feelings of regret and try to avoid this feeling of regret when making choices.

Representativeness Heuristic: A mental shortcut used to assess probability whereby the more an object appears to represent a class of objects, the more likely we believe it belongs to the class of objects.

Rule Utilitarianism: An approach to utilitarianism that argues that rather than considering every decision separately, general rules should be followed which tend to lead to the greatest good for the greatest number.

Satisficing: Theory of decision-making that argues that in the face of uncertainty and incomplete information, decision makers work to satisfy basic needs, even if the choice does not optimize overall utility.

Self-Control: Control of behavior using internal controls (such as diligence or morality) rather than external controls (such as rules and laws). Self-control is exhibited when one chooses things that are harder at the moment. Related to optimization.

Selfishness: Type of decision-making when a person chooses the option which benefits themselves but harms others.

Social-Cooperation: Type of decision-making when a person chooses the option which is costly to themselves but benefits others.

Subjective Expected Utility Theory: An extension of expected utility theory which is used when a probability of an outcome or event cannot be determined in advance and subjective probabilities, determined by the decision maker, must be used.

Tragedy of the Commons: Description of conflict where each individual, seeking out their own selfish best interest, utilizes common resources in a way which leads to a tragic outcome that affects the entire group.

Undermatching: A deviation from matching in which animals express relative indifference to the alternatives in a two choice procedure, regardless of the outcomes of each alternative.

Universal Human Morality: Human condition described by C. S. Lewis which is shared by all individuals which is an internal control which helps keep selfish behavior in check.