01-3: Approaches to Studying Learning

Psychology of Learning

Module 01: What is Learning?

Part 3: Approaches to Studying Learning

Looking Back

In Parts 1 and 2, we established the foundation for studying learning—defining it as a hypothetical construct (an inferred change in mental state resulting from experience), distinguishing it from performance and maturation, and exploring how evolution shapes what organisms can learn through prepared, unprepared, and contraprepared associations. Now we turn to different questions: How should we study learning? What theoretical frameworks are most useful? And why has so much learning research focused on animals rather than humans?

In Parts 1 and 2, we established the foundation for studying learning—defining it as a hypothetical construct (an inferred change in mental state resulting from experience), distinguishing it from performance and maturation, and exploring how evolution shapes what organisms can learn through prepared, unprepared, and contraprepared associations. Now we turn to different questions: How should we study learning? What theoretical frameworks are most useful? And why has so much learning research focused on animals rather than humans?

Two Major Approaches to Studying Learning

Throughout the history of learning psychology, researchers have debated not just what learning is, but how it should be studied. Two major approaches have dominated the field: the behavioral approach and the cognitive approach. While these approaches share the goal of understanding learning, they differ fundamentally in their methods, assumptions, and what they consider legitimate scientific evidence (Bower & Hilgard, 1981).

The Behavioral Approach

The behavioral approach to learning emphasizes observable behaviors and their environmental causes, deliberately avoiding discussion of unobservable mental states or processes (Watson, 1913; Skinner, 1938). Behaviorists argue that psychology should be an objective science, studying only what can be directly observed and measured. Thoughts, feelings, intentions, and other mental phenomena are considered scientifically problematic because they cannot be directly observed.

John B. Watson (1913) laid out the behaviorist manifesto in his famous article “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It.” He argued that psychology had failed to become a natural science because it focused on consciousness and introspection. Instead, Watson proposed that psychology should study behavior—the objective, measurable responses organisms make to environmental stimuli.

B.F. Skinner (1938, 1953) developed this approach further, arguing that internal mental states were not just difficult to study—they were unnecessary for explaining behavior. According to Skinner, we can predict and control behavior perfectly well by understanding the relationships between environmental stimuli and behavioral responses, without reference to what happens inside the organism’s mind.

This approach led to an emphasis on rigorous experimental control and operational definitions. Behaviorists insisted on defining concepts in terms of observable operations. Learning wasn’t defined by what happens in the mind, but by measurable changes in response frequency, latency, or magnitude. Hunger wasn’t a feeling, but hours of food deprivation. Reinforcement wasn’t pleasure, but any stimulus that increases response frequency.

The Behavioral View of Intervening Variables

Intervening variables are theoretical constructs that are inferred to exist between observable stimuli and responses (Tolman, 1932; MacCorquodale & Meehl, 1948). Examples include hunger, thirst, motivation, attention, and learning itself. These variables “intervene” between what we can observe (environmental inputs and behavioral outputs).

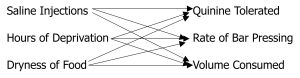

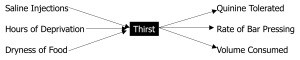

Skinner (1950) was deeply skeptical of intervening variables. He argued they unnecessarily complicate our understanding without improving prediction or control. Consider this example: We might observe that hours of water deprivation predict the rate of bar pressing for water. We could represent this simply as:

Hours of Water Deprivation → Rate of Bar Pressing

Or we could introduce an intervening variable:

Hours of Water Deprivation → Thirst → Rate of Bar Pressing

Skinner argued that the second formulation adds nothing. We still measure hours of deprivation and rate of bar pressing. The concept of “thirst” doesn’t improve our predictions or give us any new control over behavior. It just adds an unnecessary step. By the criterion of parsimony (Occam’s razor), the simpler explanation should be preferred (Skinner, 1950).

For strict behaviorists, this reasoning applied to learning itself. Why talk about learning as an internal change when we can directly study how experience (environmental events) affects performance (observable behavior)? The intervening construct of learning seems to add complexity without benefit.

The Cognitive Approach

The cognitive approach to learning emerged partly from dissatisfaction with behaviorism’s constraints (Miller, Galanter, & Pribram, 1960; Neisser, 1967). Cognitive psychologists argue that understanding learning requires understanding mental processes—memory, attention, expectation, problem-solving, and reasoning. These internal processes cannot be ignored simply because they’re difficult to observe directly.

Neal Miller and other cognitive pioneers argued that intervening variables, far from being unnecessary complications, could actually simplify our understanding of complex relationships (Miller, 1959). A more complex scenario illustrates the value of intervening variables:

Food deprivation, water deprivation, and sexual deprivation all affect multiple behaviors—eating, drinking, mating, exploring, aggression, and more. If we tried to map every specific deprivation state to every specific behavior, we’d need dozens of separate relationships. But if we introduce the intervening variable of “motivation,” we can understand all these relationships more parsimoniously:

Various Deprivation States → Motivation → Various Goal-Directed Behaviors

This single intervening variable (motivation) helps explain multiple input-output relationships, actually simplifying rather than complicating our understanding (Miller, 1959).

Cognitive psychologists also point out that other sciences use theoretical constructs we can’t directly observe. Physicists talk about electrons, quarks, and dark matter. Chemists discuss molecular bonds. Biologists describe genes and natural selection. None of these can be directly observed—they’re all inferred from their effects. Psychology shouldn’t handicap itself by refusing to use similar theoretical constructs (Miller, Galanter, & Pribram, 1960).

Learning as an Intervening Variable

As we established in Part 1, learning is itself an intervening variable—a hypothetical construct inferred from the relationship between experience and performance. We can diagram this relationship:

Experience (Practice, Training) → Learning → Performance (Observable Behavior)

The cognitive approach embraces this complexity. Learning and performance are not the same thing, and understanding their relationship requires acknowledging that learning is an internal change that may or may not be expressed in current behavior (Tolman, 1932). Remember latent learning—rats that explored mazes learned their layout even when they didn’t perform that knowledge until it became useful (Tolman & Honzik, 1930).

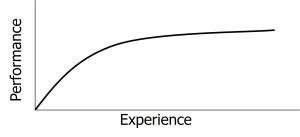

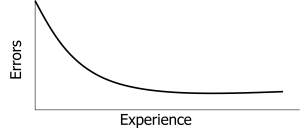

Learning curves provide a visual representation of learning as an intervening variable (Ebbinghaus, 1885/1913). A learning curve is a graph showing how performance changes with practice or experience. The curve itself represents our inference about the learning process based on observable performance measures.

Different types of learning produce differently shaped learning curves. Simple motor skills often show negatively accelerated curves—rapid improvement early, then slower gains. Complex cognitive skills might show S-shaped curves—slow initial progress, rapid middle gains, then plateaus. Some learning shows sudden insight rather than gradual improvement. The shape of the learning curve tells us something about the nature of the learning process (Newell & Rosenbloom, 1981).

Complementary Rather Than Competing

Today, most learning researchers recognize that behavioral and cognitive approaches are complementary rather than incompatible (Rescorla, 1988; Gallistel, 1990). The behavioral approach’s emphasis on rigorous methodology, operational definitions, and careful experimental control remains essential. Its focus on observable behavior keeps psychology grounded in measurable phenomena.

At the same time, the cognitive approach’s willingness to theorize about internal processes has proven invaluable. Modern neuroscience allows us to observe brain activity during learning, making “mental processes” less mysterious and more measurable (Kandel, 2001). Computational models of learning can be tested against both behavioral and neural data (Sutton & Barto, 1998).

Most contemporary researchers adopt a methodologically behavioral but theoretically cognitive stance. They maintain behavioral rigor in their experiments while freely theorizing about cognitive and neural mechanisms that might explain their results. This integrative approach has proven highly productive (Domjan, 2015; Bouton, 2016).

The Role of Animal Research in Learning

A notable feature of learning research is how prominent animal studies have been. Much of what we know about learning comes from research with rats, pigeons, dogs, monkeys, and other non-human species. Why have learning psychologists relied so heavily on animal research?

Historical Context: Behaviorism & Equipotentiality

The heavy use of animal research in learning studies stems partly from the historical dominance of behaviorism and its assumption of equipotentiality. If learning follows universal laws that apply equally to all species, then studying rats or pigeons is just as valid as studying humans—and often more practical (Watson, 1913; Skinner, 1938).

Watson (1930) famously declared: “Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief, and yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.”

This extreme environmentalism assumed that learning mechanisms were basically identical across species. If that were true, animal research would directly inform our understanding of human learning. As we’ve seen from biological constraints (Part 2), this assumption was too strong—but it motivated much valuable research (Seligman, 1970).

Practical Advantages of Animal Research

Beyond theoretical assumptions, animal research offers several practical advantages (Domjan & Purdy, 1995):

Experimental Control: Researchers can control animals’ environments far more completely than humans’. They can regulate feeding schedules, control housing conditions, eliminate distractions, and ensure consistent experiences across subjects. This control is essential for isolating the effects of specific variables.

Access & Availability: Laboratory animals are available whenever researchers need them. Human participants must be recruited, scheduled around their other commitments, and can drop out of studies. Animals can be studied intensively over extended periods.

Lifespan & Generational Studies: Many animal species have much shorter lifespans than humans, allowing researchers to study multiple generations. Rats reach sexual maturity in about 5 weeks and have a gestation period of 21 days. Researchers can study inheritance of learned behaviors, effects of early experience on later learning, and age-related changes in learning—all within practical timeframes.

Ethical Considerations: Some learning research requires procedures that would be unethical with humans. Studies of brain lesions, drug effects, or extreme deprivation conditions can only be conducted with animals, following strict ethical guidelines. While animal research has its own ethical considerations, it allows investigations impossible with human participants (APA, 2012).

Simplified Systems: Animal nervous systems, while complex, are often simpler than human brains. This simplification can make it easier to identify basic mechanisms. The sea slug Aplysia, with only about 20,000 neurons (compared to the human brain’s 86 billion), has been invaluable for understanding the neural basis of learning (Kandel, 2001).

Comparative Psychology Perspective

Comparative psychology is the study of behavior across different species, examining both similarities and differences (Darwin, 1872; Thorndike, 1911). Rather than assuming all species learn identically, comparative psychologists investigate how learning mechanisms have evolved to solve different adaptive problems in different ecological niches.

This perspective recognizes that different species may have specialized learning abilities suited to their ecological needs. Rats are excellent at spatial learning because they navigate complex underground burrow systems. Pigeons excel at visual discrimination because they rely heavily on vision for navigation and food finding. Primates show sophisticated social learning because they live in complex social groups (Shettleworth, 2010).

A classic example of species differences in social learning comes from mid-20th century Britain. In the 1920s through 1940s, milk was delivered to homes in glass bottles with foil caps. Blue tits—small, social songbirds—learned to pierce the foil caps and drink the cream from the top of the bottles. Remarkably, this behavior spread rapidly across Britain, with blue tit populations in distant regions independently ‘discovering’ the technique and passing it to other birds showing cultural transmission through observation (Fisher & Hinde, 1949).

What makes this finding significant for comparative psychology is that robins—which also had access to the same milk bottles—never developed this behavior. Why the difference? Blue tits are highly social birds that forage in flocks, creating many opportunities to observe and learn from each other. Robins are territorial and solitary, rarely observing other robins feeding. The species-specific social structure of blue tits facilitated social learning in a way that robins’ solitary nature did not (Sherry & Galef, 1984). This demonstrates that learning abilities are shaped by ecological and social factors—the same environmental opportunity (milk bottles) produced different outcomes based on each species’ evolved behavioral tendencies.

Comparative research has revealed both surprising similarities and important differences across species. Basic associative learning mechanisms (which we’ll study in detail in later modules) appear broadly similar across many species, suggesting they’re evolutionarily ancient. But species differ in what they’re prepared to learn, how quickly they learn it, and how flexibly they can apply what they’ve learned (Bitterman, 1975; Macphail, 1982).

Limitations & Generalization to Humans

While animal research has been invaluable, we must be cautious about generalizing findings to humans. As we learned in Part 2, biological constraints mean species differ in what they can easily learn. Humans have unique cognitive capabilities—language, abstract reasoning, cultural transmission of knowledge—that profoundly affect our learning (Tomasello, 1999).

Some learning principles discovered in animals do generalize well to humans. Classical conditioning and operant conditioning (which we’ll study in upcoming modules) follow similar principles across many species, including humans. Basic memory processes show important similarities. But complex human learning—reading, mathematics, scientific reasoning—goes beyond what we can study in animal models.

The most productive approach integrates animal and human research. Animal studies can reveal basic mechanisms and allow experimental control impossible with humans. Human studies can test whether principles discovered in animals apply to our species and explore uniquely human learning capabilities. Together, these complementary approaches provide a comprehensive understanding of learning (Domjan, 2015).

Modern Neuroscience Integration

Modern neuroscience has strengthened the connection between animal and human learning research. Brain imaging techniques (fMRI, PET scans) allow researchers to observe human brain activity during learning. When similar neural structures and processes appear in both animal and human studies, it strengthens confidence that basic mechanisms are shared (Squire & Kandel, 2009).

For example, studies of the hippocampus—a brain structure critical for spatial and episodic memory—show remarkable similarities across species. Research in rats revealed the hippocampus’s role in spatial navigation (O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978). Human brain imaging confirmed the hippocampus activates during spatial learning and memory tasks (Maguire et al., 2000). This convergence validates both the animal model and the generalizability of findings.

Looking Forward

We’ve now completed our foundation for studying learning—understanding what it is, how biology constrains it, and how different research approaches contribute to our knowledge. In Module 02, we’ll explore the research methods and experimental designs used to study learning, then in Module 03 we’ll begin examining specific types of learning, starting with the simplest forms: reflexive behaviors, habituation, and sensitization.

Media Attributions

- Child Studying © Picjumbo is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Complex Relationship

- Intervening Variable

- Increasing Learning Curve © Jay Brown is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Decreasing Learning Curve © Jay Brown is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

An approach to studying learning that emphasizes observable behaviors & their environmental causes while avoiding discussion of unobservable mental states or processes.

Definitions that specify how variables are produced & measured in a particular study; define concepts in terms of specific operations used to manipulate or measure them; essential for replication & clear communication.

Theoretical constructs inferred to exist between observable stimuli & responses; examples include hunger, thirst, motivation, attention, & learning itself; mediate the relationship between environmental inputs & behavioral outputs.

The scientific principle (Occam's razor) that simpler explanations should be preferred over more complex ones when both account for the data equally well.

An approach to studying learning that emphasizes internal mental processes such as memory, attention, expectation, problem-solving, & reasoning, arguing that understanding learning requires understanding these unobservable processes.

Graphs showing how performance changes with practice or experience; provide a visual representation of learning as an intervening variable; different types of learning produce differently shaped curves.

The study of behavior across different species, examining both similarities & differences to understand how learning mechanisms have evolved to solve different adaptive problems.

The spread of learned behaviors through a population via social learning; behaviors pass from individual to individual through observation rather than genetic inheritance.

Learning that occurs through observing the behavior of others; the acquisition of new behaviors by watching and imitating other individuals rather than through direct experience.