02-1: The Scientific Method & Research Equipment

Psychology of Learning

Module 02: Research Methods

Part 1: The Scientific Method & Research Equipment

Looking Back

In Module 01, we established what learning is—an inferred change in mental state resulting from experience—and explored how biology constrains what organisms can learn through the concepts of prepared, unprepared, and contraprepared behaviors. We also examined how different theoretical approaches (behavioral and cognitive) contribute to our understanding of learning, and why animal research has played such a central role. Now we turn our attention to how learning is actually studied: How do researchers design experiments to isolate the effects of specific variables? What equipment and procedures have been developed to study different types of learning?

In Module 01, we established what learning is—an inferred change in mental state resulting from experience—and explored how biology constrains what organisms can learn through the concepts of prepared, unprepared, and contraprepared behaviors. We also examined how different theoretical approaches (behavioral and cognitive) contribute to our understanding of learning, and why animal research has played such a central role. Now we turn our attention to how learning is actually studied: How do researchers design experiments to isolate the effects of specific variables? What equipment and procedures have been developed to study different types of learning?

The Scientific Approach to Learning

Learning psychology is fundamentally a scientific enterprise. But what does it mean to study learning scientifically? Before we examine specific research equipment and experimental designs, we need to understand the scientific method and how it applies to learning research.

Ways of Knowing

Humans acquire beliefs through many different methods, each with strengths and limitations. Philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce (1877) identified four primary methods of fixing belief:

Method of Tenacity: Holding firmly to beliefs simply because we have always held them. This method requires little cognitive effort—we accept what we’ve always believed without questioning its validity. While comfortable, tenacity provides no mechanism for correcting false beliefs.

Method of Authority: Accepting beliefs because trusted authority figures endorse them. We might believe something because a teacher, expert, religious leader, or institution says it’s true. This method also requires little cognitive effort—we simply defer to those we perceive as knowledgeable. While efficient (we can’t personally verify everything), it fails when authorities are wrong or biased.

A Priori Method: Arriving at beliefs through pure reasoning, independent of experience. We might believe something because it ‘stands to reason’ or seems logically necessary. While reasoning is valuable, conclusions are only as good as our premises, and intuitions can mislead us.

Method of Science: Fixing beliefs through systematic empirical observation and testing. Unlike other methods, science is self-correcting—built-in mechanisms (replication, peer review, openness to disconfirmation) allow false beliefs to be identified and revised. Science combines empiricism (reliance on observation) with rationalism (logical reasoning) to generate reliable knowledge (Stanovich, 2013).

Sometimes scientific discoveries happen by accident—a phenomenon called serendipity. Pavlov’s discovery of classical conditioning is a famous example. While studying digestion in dogs, he noticed that dogs began salivating before food was presented—they had learned to associate the lab assistant’s footsteps with feeding. Rather than ignoring this ‘nuisance,’ Pavlov recognized its significance and shifted his research to study this learning process. Serendipitous discoveries remind us that careful observation can reveal unexpected phenomena, but they still require the scientific method to investigate systematically (Pavlov, 1927).

Science is a repeatable, self-correcting undertaking that seeks to understand phenomena on the basis of empirical observation (McBurney & White, 2009). This definition highlights two crucial features: empiricism (reliance on observation and data) and self-correction (willingness to revise conclusions when new evidence emerges).

Science combines empiricism with rationalism—we collect data through observation (empiricism) and use logical reasoning to interpret those data (rationalism). This combination makes science particularly powerful for answering certain types of questions (Popper, 1959).

Goals of Scientific Psychology

Scientific research in psychology, including learning research, pursues four primary goals:

Description: Accurately portraying phenomena. Before we can explain why learning occurs, we must first carefully describe what happens during learning. How does performance change with practice? What conditions affect the rate of learning? Description provides the foundation for all other scientific goals.

Explanation: Understanding why phenomena occur. Once we’ve described learning, we seek to understand the mechanisms responsible. Why does practice improve performance? What neural changes occur during learning? Explanation involves identifying causes and developing theories.

Prediction: Anticipating when phenomena will occur. Good theories allow us to predict outcomes. If we understand how reinforcement affects learning, we can predict how changes in reinforcement schedules will influence behavior.

Control: Manipulating variables to affect behavior. The ultimate test of our understanding is whether we can control learning—enhancing it when desired or preventing it when problematic. This goal has obvious practical applications for education and training (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000).

Assumptions of Scientific Psychology

Scientific research rests on several fundamental assumptions (Marx, 1963):

Determinism is the assumption that behavior is orderly and systematic, not random. Every behavior has causes that can potentially be identified. This doesn’t mean behavior is perfectly predictable—too many variables interact in complex ways—but it does mean that systematic relationships exist between variables and behavior (Hergenhahn & Olson, 2005).

Determinism implies a controversial position: if behavior is fully caused by prior conditions, is there truly free will? This philosophical question has occupied psychologists and philosophers for centuries. For scientific purposes, we adopt methodological determinism—assuming determinism for research purposes while remaining agnostic about ultimate metaphysical questions of free will (Skinner, 1971).

Discoverability: It’s possible to discover the orderly relationships governing behavior. If determinism is true but we couldn’t discover the relevant relationships, science would be futile. Fortunately, systematic research can reveal behavioral principles, though this may require clever experimental designs and sophisticated analysis (Marx, 1963).

Parsimony: When multiple explanations account for the data equally well, prefer the simpler one (Occam’s razor). This doesn’t mean reality is always simple, but we shouldn’t postulate unnecessary complexity. If we can explain learning without assuming elaborate intervening variables, we should do so (Morgan, 1894).

The Role of Theory

A theory is a set of interrelated concepts and propositions that present a systematic view of phenomena by specifying relationships among variables. Theories organize existing knowledge, generate testable predictions (hypotheses), and guide future research (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000).

Philosopher Karl Popper (1959) argued that science progresses through theory building and testing. Crucially, theories can never be conclusively proven—they can only be supported by evidence or disconfirmed. The highest status a theory can achieve is “not yet disconfirmed.” This might sound pessimistic, but it captures science’s self-correcting nature. We provisionally accept theories that have survived rigorous testing while remaining open to revision.

Good theories in learning psychology share several characteristics: they’re testable (make specific predictions), parsimonious (don’t invoke unnecessary complexity), broad in scope (explain diverse phenomena), and fruitful (generate new research). Examples include Rescorla and Wagner’s (1972) theory of classical conditioning and Skinner’s (1938) principles of operant conditioning.

Research Equipment in Learning Studies

With this scientific foundation established, we can now examine the specialized equipment learning researchers use. The apparatus chosen depends on the type of learning being studied and the species being tested. Over more than a century of research, psychologists have developed ingenious devices to isolate and measure specific learning processes.

Understanding this equipment serves multiple purposes. It helps us appreciate how classic findings were discovered, critically evaluate research methods, and understand what aspects of learning different procedures can and cannot measure.

Classical Conditioning Apparatus

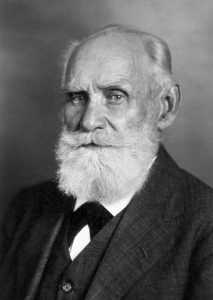

Classical conditioning (also called Pavlovian conditioning) involves learning associations between stimuli. An originally neutral stimulus comes to elicit a response after being repeatedly paired with a stimulus that naturally produces that response. This fundamental form of learning was discovered serendipitously by Ivan Pavlov while studying digestion in dogs (Pavlov, 1927).

Pavlov’s original apparatus was elegantly simple but remarkably effective. Dogs were restrained in a comfortable harness, allowing precise measurement of salivation through a surgically implanted tube (fistula) that collected saliva drops. Experimenters could present controlled stimuli—tones, lights, metronomes—and measure exactly when and how much the dogs salivated.

The key insight was that dogs naturally salivate to food (an unconditioned response to an unconditioned stimulus) but not to neutral stimuli like tones. However, after repeatedly pairing a tone with food, dogs began salivating to the tone alone. The tone had become a conditioned stimulus producing a conditioned response (Pavlov, 1927).

Modern classical conditioning research uses updated versions of Pavlov’s methods. Computer control allows precise timing of stimulus presentations. Video recording and automated sensors replace manual observation. But the basic logic remains: pair neutral stimuli with biologically significant stimuli and measure the learned association.

Classical conditioning apparatus has been adapted for many species and response systems. Researchers study eyeblink conditioning in rabbits (measuring learned eye closure), fear conditioning in rats (measuring freezing behavior), and even conditioning in sea slugs (measuring gill withdrawal). Each preparation provides insights into different aspects of associative learning (Kehoe & Macrae, 1998; Domjan, 2015).

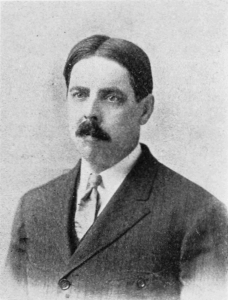

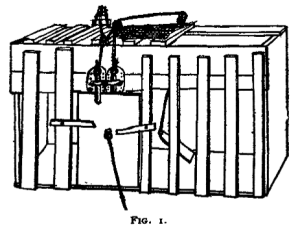

Operant Conditioning: Thorndike’s Puzzle Boxes

Operant conditioning (also called instrumental conditioning) involves learning relationships between behaviors and their consequences. Unlike classical conditioning, where the organism passively experiences stimulus pairings, operant conditioning requires the organism to actively produce responses that then have consequences (Skinner, 1938).

Edward Thorndike pioneered the study of operant conditioning with his puzzle boxes in the 1890s. A hungry cat placed inside a puzzle box could see food outside but needed to escape to reach it. Various mechanisms—pulling strings, pressing levers, stepping on platforms—would open the door. Initially, cats made random movements (trial-and-error behavior), eventually stumbling on the correct action. On subsequent trials, unnecessary behaviors dropped out and escape became faster (Thorndike, 1898, 1911).

Thorndike’s puzzle boxes demonstrated several key principles. First, learning was gradual, not sudden insight. Second, behaviors followed by “satisfying” consequences (escape and food) increased in frequency. This observation led to his Law of Effect: responses producing satisfying consequences in a situation become more likely in that situation. This principle became foundational for operant conditioning theory (Thorndike, 1911).

Reinforcement is the process by which a consequence increases the likelihood of the behavior that produced it. Food reinforced the cat’s escape behavior, strengthening that response. Modern operant conditioning research extensively studies how different types and schedules of reinforcement affect learning (Skinner, 1938).

Mazes: Studying Spatial Learning & Memory

Mazes have been workhorses of learning research since the early 1900s. Rats navigate corridors to reach a goal box containing food or escape from water, learning the correct route through trial and error (Small, 1901; Tolman, 1932).

Simple T-mazes present a single choice point: turn left or right? One arm contains reward; the other doesn’t. Even this simple apparatus yields rich data about learning, memory, and decision-making. Does the rat learn to “turn left” (a response strategy) or to “go to the place where food is” (a spatial strategy)? Elegant experiments rotating mazes or adding landmarks distinguish these possibilities (Restle, 1957).

Y-mazes add complexity with three arms radiating from a central choice point. Multiple-unit mazes chain together choice points, creating complex navigation problems. The classic Hampton Court maze, modeled after the famous hedge maze in England, presented rats with a series of choice points requiring multiple correct turns to reach the goal (Small, 1901).

The radial arm maze, developed by Olton and Samuelson (1976), revolutionized spatial memory research. Eight (or more) identical arms radiate from a central platform, each baited with food. Efficient foraging requires remembering which arms have already been visited—a test of working memory. Rats learn to visit each arm once without revisiting depleted arms, demonstrating impressive spatial memory capabilities (Olton & Samuelson, 1976).

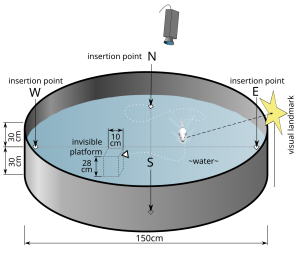

The Morris water maze, developed in the 1980s, became enormously influential in neuroscience research. Rats swim in a pool of opaque water searching for a hidden platform just below the surface. Spatial cues around the room (visual landmarks) allow rats to learn the platform’s location. This apparatus powerfully demonstrates spatial learning and is widely used to study the hippocampus’s role in memory (Morris, 1981).

The Operant Conditioning Chamber (Skinner Box)

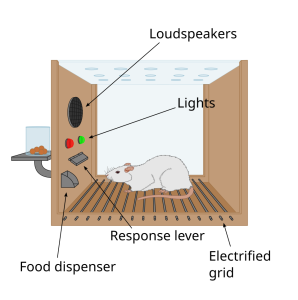

B.F. Skinner developed the operant conditioning chamber (informally called the “Skinner box”) in the 1930s to study operant conditioning with maximum experimental control (Skinner, 1938). This apparatus revolutionized learning research by allowing automated, continuous measurement of behavior over extended periods.

A typical chamber is a small enclosure (often for rats or pigeons) containing a response manipulandum—a lever for rats to press or a key for pigeons to peck. A food hopper delivers small food pellets as reinforcement. The chamber is soundproof and visually isolated, eliminating distracting stimuli. Most importantly, electromechanical (now computerized) equipment automatically records every response and controls reinforcement delivery (Skinner, 1938).

This automation was transformative. Previously, experimenters hand-recorded behaviors and manually delivered rewards—tedious, error-prone, and limited in duration. Skinner boxes could run experiments 24 hours a day, recording thousands of responses with perfect accuracy. This allowed detailed analysis of how reinforcement schedules affect behavior patterns (Ferster & Skinner, 1957).

Modern operant chambers include sophisticated capabilities: multiple response options (several levers or keys), discriminative stimuli (lights, tones), and computerized control of complex reinforcement contingencies. Researchers study choice behavior, timing, stimulus control, and self-control using these versatile apparatus (Catania, 2013).

Looking Forward

We’ve established the scientific foundations of learning research and surveyed some classic research equipment. In Part 2, we’ll delve deeper into research variables—independent variables, dependent variables, and the crucial concept of experimental control—while exploring additional specialized equipment including apparatus for studying discrimination learning, motor skills, and verbal learning.

Media Attributions

- Operant Conditioning Involves Choice © Mark Bouton is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

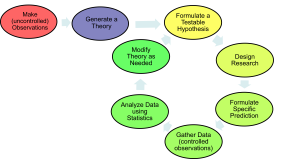

- The Scientific Method © Jay Brown is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Ivan Pavlov © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- One of Pavlov’s Dogs © Rklawton is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Edward Lee Thorndike © Popular Science Monthly is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Original “Puzzle Box” Apparatus Design © EJ Thorndike is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Morris Water Maze © Samueljohn is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Skinner is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Skinner Box © AndreasJS is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Pigeon in Skinner Box © Google Gemini is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

A way of fixing belief by holding firmly to ideas simply because one has always believed them; requires little cognitive effort and provides no mechanism for correcting false beliefs.

A way of fixing belief by accepting ideas because trusted authority figures (experts, teachers, institutions) endorse them; efficient but fails when authorities are wrong.

A way of fixing belief through pure reasoning, independent of empirical experience; conclusions depend on the quality of premises.

An accidental or unexpected discovery in research; finding something valuable while looking for something else (e.g., Pavlov discovering classical conditioning while studying digestion).

Observation based on sensory experience and data collection; the foundation of scientific knowledge.

The reliance on observation & data collection to understand phenomena; a defining feature of science that distinguishes it from pure rationalism or faith-based ways of knowing.

The philosophical position that knowledge comes from logical reasoning.

A goal of science involving accurately portraying phenomena.

A goal of science involving understanding why phenomena occur by identifying causes and developing theories.

A goal of science involving anticipating when phenomena will occur based on theoretical understanding.

The assumption that behavior is orderly & systematic rather than random; every behavior has causes that can potentially be identified, though perfect prediction may be impossible due to complexity.

Assuming determinism for research purposes while remaining agnostic about ultimate metaphysical questions of free will.

The assumption that it is possible to discover the orderly relationships governing behavior.

The scientific principle (Occam's razor) that simpler explanations should be preferred over more complex ones when both account for the data equally well.

A set of interrelated concepts & propositions that present a systematic view of phenomena by specifying relationships among variables; theories organize knowledge, generate testable predictions, & guide research.

A testable prediction derived from a theory.

The status of a theory that has been contradicted by evidence; in science, theories can be supported or disconfirmed but never conclusively proven.

A learning process in which a neutral stimulus comes to elicit a response after being paired with an unconditioned stimulus.

In classical conditioning, a stimulus that naturally elicits a response without prior learning.

In classical conditioning, a stimulus that naturally elicits a response without prior learning.

In classical conditioning, a previously neutral stimulus that comes to elicit a response after being paired with an unconditioned stimulus.

In classical conditioning, the learned response elicited by the conditioned stimulus.

A type of learning involving relationships between behaviors & their consequences; unlike classical conditioning, requires the organism to actively produce responses that have consequences; also called instrumental conditioning.

Apparatus developed by Thorndike to study trial-and-error learning; animals must discover how to escape to reach food.

Thorndike's principle that responses producing satisfying consequences in a situation become more likely in that situation.

The process by which a consequence increases the likelihood of the behavior that produced it; a fundamental principle of operant conditioning discovered through Thorndike's puzzle box experiments.

A simple maze with a single choice point where the animal turns left or right.

A maze with three arms radiating from a central choice point.

Apparatus with multiple arms radiating from a central platform; used to study spatial working memory.

The cognitive system responsible for temporarily holding and manipulating information; tested by radial arm maze performance.

Apparatus in which rats swim in opaque water to find a hidden platform; widely used to study spatial learning and hippocampal function.

Apparatus developed by B.F. Skinner for studying operant conditioning with automated recording and reinforcement delivery; informally called a Skinner box.

The response device in an operant conditioning chamber, such as a lever for rats to press or a key for pigeons to peck.