03-1: Elicited Behaviors

Psychology of Learning

Module 03: Unlearned Adaptive Behaviors

Part 1: Elicited Behaviors

Looking Back

In Modules 01 and 02, we established the foundations for studying learning scientifically—defining learning as an inferred change in mental state resulting from experience, distinguishing it from performance and other behavioral changes, and examining how to conduct rigorous experiments. We’re now ready to begin our systematic study of specific types of behavior change, starting with the simplest end of the behavioral spectrum: behaviors that don’t require learning at all. Understanding these unlearned behaviors provides the foundation for appreciating true learning when we encounter it in later modules.

The Spectrum of Stimulus-Response Connections

Organisms constantly respond to environmental stimuli. When you touch a hot stove, you reflexively jerk your hand away. When a sunflower turns toward the sun, it displays a growth response to light. When a male stickleback fish sees another male’s red belly, it attacks. These diverse behaviors all involve stimulus-response connections, but they differ fundamentally in their mechanisms and in whether learning is involved.

We can arrange stimulus-response connections along a continuum from completely unlearned to fully learned: reflexes → tropisms → fixed action patterns → habituation and sensitization → classical conditioning → operant conditioning → observational learning. The innate responses work fine as long as the environment remains stable, but in a changing environment, only learning allows flexible adaptation (Domjan, 2015).

Instincts: Unlearned Sequences of Activities

Instincts are unlearned sequences of activities that are characteristic of all members of a species (of the same sex), are adaptive for survival or reproduction, and require only an initial stimulus to trigger them (unlike tropisms which require continuous stimulation). Instincts include reflexes, kineses, taxes, fixed action patterns, and reaction chains (Tinbergen, 1951).

The concept of instinct has a complicated history in psychology. Early behaviorists like John Watson rejected instinct as unscientific, preferring to explain behavior through learning. However, European ethologists like Konrad Lorenz and Niko Tinbergen demonstrated that many complex behaviors occur without learning, shaped by evolution to solve specific adaptive problems (Lorenz, 1937; Tinbergen, 1951).

Reflexes: The Simplest Stimulus-Response Connection

A reflex (more precisely, an unconditioned reflex) is an innate response that is elicited by a specific stimulus. Reflexes are the simplest form of behavior, involving automatic, involuntary responses to specific stimulation (Sherrington, 1906).

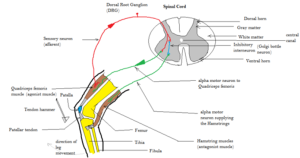

Simple reflexes have three neural components forming a reflex arc:

Afferent neurons (sensory neurons) carry sensory signals from receptors to the central nervous system (spinal cord and brain). These neurons detect the stimulus and transmit information about it (Sherrington, 1906).

Interneurons are spinal cord neurons that connect afferent (sensory) neurons and efferent (motor) neurons. These provide the connection that allows sensory input to trigger motor output (Sherrington, 1906).

Efferent neurons (motor neurons) carry motor signals from the central nervous system to skeletal muscles and internal organs. These neurons trigger the behavioral response (Sherrington, 1906).

The classic example is the patellar tendon reflex—your leg kicks forward when a doctor taps just below your kneecap. The tap stretches the tendon, activating sensory receptors. Afferent neurons carry this signal to the spinal cord, where interneurons connect to efferent neurons, which trigger leg muscles to contract. This all happens without conscious awareness or decision-making.

Common Human Reflexes

Humans display numerous reflexes, many of which have clear adaptive value:

Leg-flexion reflex: A painful stimulus delivered to the leg causes the leg to flex, pulling it away from danger. This protective reflex operates faster than conscious pain perception—you jerk your foot away from a tack before you consciously feel the pain.

Investigatory reflex: A novel or unexpected stimulus elicits inspection and investigatory behaviors. This reflex orients you toward potentially important environmental changes, allowing you to assess whether they’re threats or opportunities.

Pupillary reflex: Bright light causes pupils to constrict (protecting the retina); darkness causes dilation (gathering more light). Emotional arousal also affects pupil size, which is why pupil dilation can indicate interest or attraction.

Infant Reflexes

Newborn infants display several reflexes that typically disappear as the nervous system matures:

Babinski reflex: When the sole of an infant’s foot is stimulated, the toes fan out. This reflex typically disappears by age 2, replaced by the plantar reflex (toe curling) in older children and adults. Persistence of the Babinski reflex past age 2 may indicate neurological problems.

Moro reflex: A startle-like response occurring when an infant experiences sudden motion or hears a loud noise. The infant throws arms outward and then brings them back to the body. This may have evolved to help infants cling to caregivers.

Rooting reflex: Rubbing a finger along an infant’s cheek causes the infant to turn its head in that direction and begin sucking motions. This reflex helps infants find the mother’s nipple for feeding.

Grasp reflex: Stimulation of an infant’s palm causes the infant to close its hand tightly around the stimulating object. Newborns can grasp so strongly they can support their own weight. This may be an evolutionary remnant of primate infants clinging to mothers’ fur (Darwin, 1872).

Tropisms: Whole-Body Forced Movements

Whereas reflexes involve movement of one part of the body, a tropism involves movement of the entire body. A tropism is behavior that is forced by a particular stimulus—the organism moves in a mechanistic way toward or away from the stimulus (Loeb, 1918).

Both animals and plants display tropisms. The most familiar example is heliotropism—plants growing toward the sun. The plant doesn’t “decide” to move toward light; rather, differential growth rates on shaded versus illuminated sides cause the plant to bend toward the light source. This is a purely mechanistic response.

John B. Watson, the founder of behaviorism, was very interested in tropisms. He reasoned that a complete listing of an organism’s reflexes and tropisms would provide a baseline for identifying which behaviors were learned. If a behavior couldn’t be explained by innate reflexes or tropisms, it must be learned (Watson, 1913).

Kineses: Random Movements

Kineses are random movements that continue unti

l favorable conditions are encountered. Unlike tropisms, kineses aren’t directed—the organism doesn’t move toward or away from anything specific, but simply moves more or less depending on conditions (Fraenkel & Gunn, 1940).

Wood lice (terrestrial crustaceans that breathe through gills) provide a classic example. These animals

need humidity to survive but have no way of sensing distant humidity levels. Instead, they use a simple mechanism: they move randomly, but slow down when they encounter humid areas. This causes them to spend more time in humid places without actually navigating toward humidity.

The wood louse uses a comparator mechanism: if actual humidity falls below a reference level, movement ensues. Movement is random and occurs until a humid location has been reached. This elegant solution requires no sensory ability to detect distant humidity—just the ability to detect local conditions and adjust activity accordingly (Fraenkel & Gunn, 1940).

Taxes: Directed Movements

Taxes are directed movements toward or away from a stimulus source. Unlike kineses (which are random), taxes involve oriented movement in a specific direction relative to the stimulus (Fraenkel & Gunn, 1940).

Maggots demonstrate negative phototaxis (movement away from light). If a bright light shines on a maggot, it will turn and walk away from the light. The maggot swings its head as it moves, always proceeding toward the area with the least light. This head-swinging behavior allows it to compare light intensity on left versus right and adjust direction accordingly.

Ants navigate using the sun, keeping it at a constant angle to ensure they travel in a straight line. They then reverse the angle 180° to return home. This sophisticated navigation can be fooled by artificial lights—if you replace the sun with a lamp and then move the lamp, the ants’ travels change accordingly. They’re not using a cognitive map; they’re executing a fixed behavioral algorithm based on maintaining a constant angle to a bright light source (Wehner, 1992).

Fixed Action Patterns: Stereotyped Response Sequences

A fixed action pattern (also called modal action pattern) is an elicited, stereotyped response sequence that all members of a species display. When triggered, these behaviors unfold in a characteristic sequence that appears largely unchanged by individual experience (Lorenz, 1937; Tinbergen, 1951).

Ethology is the study of animal behavior in natural environments. Ethologists called these response sequences “fixed action patterns” because when elicited, they appeared to be displayed in exactly the same manner by all members of the species (Tinbergen, 1951).

The key feature of fixed action patterns is that they’re triggered by specific stimuli called sign stimuli. Once triggered, the entire behavioral sequence typically runs to completion even if the original stimulus disappears or circumstances change.

Sign Stimuli & Releasing Mechanisms

A sign stimulus is a special, specific stimulus feature that elicits a fixed action pattern. This stimulus can be a specific feature of the environment or of another animal. Sign stimuli act like keys that unlock specific behavioral programs (Tinbergen, 1951).

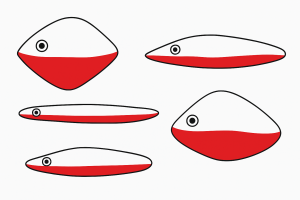

Niko Tinbergen’s research on three-spined stickleback fish provides a classic example. Male sticklebacks defend territory from other males and court females. Tinbergen noticed that male sticklebacks in laboratory tanks responded aggressively to red mail trucks passing by outside the window. This observation led to clever experiments testing various fish models.

They found that the bright red spot on the male’s belly was the crucial sign stimulus. Fish-like models

with red spots were attacked; fish-like models without red spots were ignored. Even crude shapes resembling fish triggered attacks if they had red coloration, while realistic fish models without red were ignored. The specific feature—redness—mattered more than overall realism (Tinbergen, 1951).

Fixed Action Patterns in Mammals

Nut-burying behavior in squirrels demonstrates how fixed action patterns can be innate yet inflexible. A squirrel raised in isolation, receiving only liquid food, well-fed, and living on a solid floor was tested with nuts. When given nuts, the squirrel ate until full, then carried the remaining nuts around searching for “landmarks” like corners. The squirrel then attempted to bury nuts using stereotyped movements—scratching the solid floor, placing the nut, and making covering motions—despite the complete inappropriateness of these actions (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1975).

This demonstrates both the innateness of fixed action patterns (the squirrel never saw nut-burying) and their inflexibility (the squirrel performed the behavior despite its uselessness on a solid floor). The behavioral program exists innately but can’t be modified by obviously inappropriate circumstances.

Fixed Action Patterns in Humans

Do humans have fixed action patterns? Research suggests yes, though human behavior is more flexible than other species. Eibl-Eibesfeldt documented rapid eyebrow raising as a greeting display across diverse cultures including isolated groups. Because this behavior appeared universally, he concluded it was a human fixed action pattern—an innate component of greeting behavior (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1972).

Contagious yawning provides another candidate. Seeing someone yawn often triggers yawning in observers. Research shows that the entire face serves as the sign stimulus—simply seeing a mouth or eyes alone isn’t sufficient to trigger contagious yawning (Provine, 2005).

Beyond specific behaviors like eyebrow flashing and contagious yawning, anthropologist Donald Brown (1991) compiled a list of human universals—traits, behaviors, and institutions that appear in every known human culture. This list includes hundreds of items ranging from basic behaviors (e.g., facial expressions of emotion) to complex social institutions (e.g., marriage, music, religion, dance, and hospitality to guests). The existence of these universals suggests that certain behavioral tendencies are part of our evolved human nature rather than products of specific cultural learning. Just as fixed action patterns represent species-typical behaviors in other animals, human universals may represent our species’ characteristic behavioral repertoire—the innate foundation upon which cultural variation is built (Brown, 1991).

Facial expressions of emotion—happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, surprise—show remarkable cross-cultural consistency, suggesting they may be fixed action patterns with evolutionary origins (Ekman, 1973). However, humans also show cultural modulation of emotional expression, demonstrating interaction between innate tendencies and learning.

Reaction Chains: Sequences of Fixed Action Patterns

A reaction chain is a sequence of fixed action patterns where the completion of one pattern provides the stimulus for the next. Each fixed action pattern in the sequence serves as both a response to the previous stimulus and a stimulus for the next response (Tinbergen, 1951).

A reaction chain is a sequence of fixed action patterns where the completion of one pattern provides the stimulus for the next. Each fixed action pattern in the sequence serves as both a response to the previous stimulus and a stimulus for the next response (Tinbergen, 1951).

Hermit crabs provide an excellent example. When a hermit crab encounters a suitable shell, it performs approximately eight separate fixed action patterns in sequence: approaching the shell, examining it with antennae, turning the shell, inserting abdomen, withdrawing from old shell, inserting into new shell, and adjusting position. Each action flows into the next, creating a smooth behavioral sequence.

More complex behaviors like migration and imprinting involve multiple environmental and internal cues. Bird migration is triggered by gradual changes in day length interacting with hormonal changes. The behavior involves complex navigation using multiple cues (sun position, stars, magnetic fields) but still relies on innate behavioral programs (Gwinner, 1996).

Elicited Behaviors Are Adaptive

All of these elicited behaviors—reflexes, tropisms, fixed action patterns, reaction chains—evolved because they enhance survival and reproduction. The adaptive nature of elicited behaviors explains why they’re so common across species. Natural selection has shaped innate behavioral responses to solve recurrent problems: finding food, avoiding danger, reproducing, caring for offspring.

The blue-footed booby provides a striking example of how elicited behaviors serve adaptive functions through a series of innate response patterns. Each breeding season, a pair typically produces two chicks, but food scarcity can trigger siblicide, where the larger chick kills its smaller sibling. This behavior is not learned; it unfolds through a chain of fixed action patterns and reflexes that have evolved to maximize survival under harsh conditions. The sign stimulus for aggression is often the smaller chick’s begging movements or vocalizations, which elicit pecking and pushing behaviors from the dominant chick. These actions occur in a stereotyped sequence—initial pecks escalate to forceful jabs and eventually pushing the weaker chick out of the nest—demonstrating the inflexibility characteristic of fixed action patterns. Reflexive components, such as the rapid pecking response to visual cues of movement, combine with these patterned sequences to ensure that the dominant chick monopolizes limited resources. While siblicide may seem brutal, it is an adaptive solution to unpredictable food availability: by eliminating competition, the surviving chick has a higher probability of reaching fledging. This illustrates how innate behavioral programs, though rigid, are shaped by natural selection to solve critical problems of survival and reproduction in variable environments.

However, as we learned in Module 01, innate behaviors have limitations. They work well in stable environments but become problematic when environments change. An organism relying solely on fixed action patterns can’t adapt to novel situations. This is where learning becomes essential—it provides the flexibility to adapt to changing, unpredictable environments.

Looking Forward

We’ve surveyed the landscape of unlearned elicited behaviors—reflexes, tropisms, kineses, taxes, fixed action patterns, and reaction chains. In Part 2, we’ll explore habituation and sensitization—phenomena that occur when stimuli are presented repeatedly. These processes occupy a borderline position between purely reflexive responses and true learning, and understanding them is essential for understanding more complex forms of learning like classical conditioning.

Media Attributions

- Patellar Tendon Reflex Arc © Amiya Sarkar is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Woodlouse Collage is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Male Stickleback © Viridiflavus is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Stickleback Models © Microsoft Copilot adapted by Jay Brown is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Reaction Chain © Microsoft Copilot adapted by Jay Brown is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Blue-footed Booby © Snowmanradio is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

Complex, species-typical behavior patterns that occur without prior experience; innate behaviors that don't require learning, though they can be modified by experience.

An innate, automatic, involuntary response elicited by a specific stimulus; the simplest form of behavior.

The three-component neural pathway underlying simple reflexes: afferent neurons, interneurons, and efferent neurons.

Sensory neurons that carry signals from receptors to the central nervous system; the first component of a reflex arc.

Stimuli produced by the nervous system and internal organs (thoughts, memories, physiological states) that can trigger emotional responses.

Motor neurons that carry signals from the central nervous system to muscles and organs; the final component of a reflex arc.

The knee-jerk reflex in which tapping below the kneecap causes the leg to kick forward; a classic example of a simple reflex arc.

A protective reflex in which a painful stimulus causes the leg to flex and withdraw from the source of pain.

A reflex in which novel or unexpected stimuli elicit inspection and investigatory behaviors.

A reflex in which bright light causes pupil constriction and darkness causes dilation.

An infant reflex in which stimulation of the sole of the foot causes the toes to fan out; typically disappears by age 2.

An infant startle reflex in which sudden motion or loud noise causes the arms to extend outward and then return to the body.

An infant reflex in which stimulation of the cheek causes the head to turn toward the stimulus and sucking motions to begin.

An infant reflex in which stimulation of the palm causes the hand to close tightly around the stimulating object.

A whole-body movement forced by a particular stimulus; the organism moves mechanistically toward or away from the stimulus.

A growth response in plants toward or away from a stimulus, such as a sunflower turning toward the sun.

Random movements that continue until favorable conditions are encountered; undirected activity that increases or decreases based on local conditions.

In kineses, the mechanism that compares current conditions to a reference level and initiates movement when conditions are unfavorable.

Directed movements toward or away from a stimulus source; oriented movement in a specific direction relative to the stimulus.

Directed movement away from a light source; demonstrated by maggots.

An elicited, stereotyped response sequence displayed by all members of a species; triggered by sign stimuli and runs to completion once initiated.

The study of animal behavior in natural environments; ethologists identified fixed action patterns and sign stimuli.

A specific stimulus feature that elicits a fixed action pattern; acts like a key that unlocks a specific behavioral program.

Traits, behaviors, and institutions (such as music, religion, marriage, and facial expressions of emotion) that appear in every known human culture; evidence of evolved species-typical behavioral tendencies.

A sequence of fixed action patterns where completion of one pattern provides the stimulus for the next.