6.4 Cultural Ecology

Perspectives: An Open Invitation to Cultural Anthropology 2 e

CULTURAL ECOLOGY

Early Cultural Ecologists

One of the earliest anthropologists to think systematically about the environment was Leslie White. His work built on earlier anthropological concepts of cultural evolution—the idea that cultures, like organisms, evolve over time and progress from simple to more complex. White described how cultures evolved through their ability to use energy as they domesticated plants and animals, captured the energy stored in fossil fuels, and developed nuclear power.[1] From this perspective, “human cultural evolution was best understood as a process of increasing control over the natural environment” through technological progress.[2] White’s conclusions are at odds with Franz Boas’ historical particularism, which rejected theories based on evolution that labeled cultures as more advanced or less advanced than others and instead looked at each society as a unique entity that had developed based on its particular history. Like earlier anthropologists, White viewed anthropology as a natural science in which one could generate scientific laws to understand cultural differences. His model is useful, however, when exploring the nature of change as our society increasingly harnessed new sources of energy to meet our wants and needs. He was writing at a time when the U.S. economy was booming and our technological future seemed promising, before the environmental movement raised awareness about harm caused by those technologies.

Anthropologist Julian Steward first used the term cultural ecology to describe how cultures use and understand their environments. His fieldwork among the Shoshone emphasized the complex ways they had adapted to the dry terrain of the Great Basin between the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountain ranges. He described how a hunting and gathering subsistence economy that relied on pine nuts, grass seeds, berries, deer, elk, sheep, antelope, and rabbits shaped Shoshone culture. Their detailed knowledge of various microclimates and seasonal variations in resource availability structured their migration patterns, social interactions, and cultural belief systems.[3] Rather than looking for single evolutionary trajectories for cultures as White had done, Steward looked for multiple evolutionary pathways that led to different outcomes and stressed the variety of ways in which cultures could adapt to ecological conditions.

Both White and Steward were influenced by materialism, a Marxist concept that emphasized the ways in which human social and cultural practices were influenced by basic subsistence (economic) needs. Both were trained as scientists, which shaped how they looked at cultural variation. Steward was also influenced by processual archaeology, a scientific approach developed in the 1960s that focused primarily on relationships between past societies and the ecological systems they inhabited. The shift in anthropology represented by White and Steward’s work led to increased use of scientific methods when analyzing and interpreting data. In subsequent decades, movements in both anthropology and archaeology criticized those scientific perspectives, challenging their objectivity, a process I examine in greater detail later in this chapter.

Pigs and Protein

Subsequent anthropologists built on the work of White and Steward, looking for ecological explanations for cultural beliefs and practices. They also drew on newly developed computer science to think about dynamic feedback systems in which cultural and ecological systems self-regulate to promote social stability—homeostasis. Some fascinating examples of this work include Roy Rappaport’s work in Papua New Guinea and Marvin Harris’ work in India.

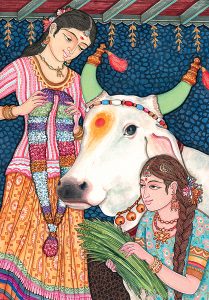

Marvin Harris examined Hindu religious beliefs about sacred cattle from functional and materialist perspectives. Among Hindus in India, eating beef is forbidden and cows are seen as sacred animals associated with certain deities. From the perspective of a Western beef-loving country, such beliefs may seem irrational. Why would anyone not want to eat a juicy steak or hamburger? Rejecting earlier academics who regarded the Hindu practice as illogical, Harris argued that the practice makes perfect sense within the Hindu ecological and economic system. He argued that cows were sacred not because of cultural beliefs; instead, the cultural beliefs existed because of the economic and ecological importance of cows in India. Thus, Hindu restrictions regarding cows were an “adaptive” response to the local ecological system rather than the result of Hindu theology.[4] Harris explored the importance of cattle for milk production, dung for fuel and fertilizer, labor for plowing, and provision of meat and hides to the lowest caste, untouchables, who were able to slaughter and eat cows and tan their hides because they were already seen as ritually impure.

Roy Rappaport examined subsistence practices of the Tsembaga in Highland New Guinea, a group that planted taro, yams, sweet potatoes, and sugar cane and raised pigs. Rappaport used scientific terms and concepts such as caloric intake, carrying capacity, and mutualism to explain methods used by the Tsembaga to manage their resources. A population of pigs below a certain threshold provided a number of benefits, such as keeping villages clean by eating refuse and eating weeds in established gardens that had relatively large fruit trees that would not be damaged by the pigs. Once the population reached the threshold, the pigs ate more than weeds and garbage and began to create problems in gardens. In response, the people used periodic ritual feasts to trim the population back, returning the ecological system to equilibrium. Rappaport, like Harris, used ecological concepts to understand the Tsembaga subsistence practices, thus downplaying the role of cultural beliefs and emphasizing ecological constraints.

These early cultural ecologists viewed cultures as trying to reach and maintain social and ecological equilibrium. This idea aligned with ecological thinking at the time that emphasized the balance of nature and the importance of the various components of an ecosystem in maintaining that balance. However, environments and cultures were rapidly changing as colonization, globalization, and industrialization spread throughout the world. In many of those early cases, anthropologists had ignored the larger processes.

As ecologists began to develop more-complex models of how ecosystems change through long-term dynamic processes of succession and disturbances (such as storms, droughts, and El Nino events), anthropological approaches to the environment also changed. The next sections examine those shifts in anthropology as environmental movements developed in response to increasing degradation of natural environments.

Early anthropologists were notable for their attempts to understand how different groups of people interacted with their environments over time. Their work paved the way for future environmental anthropologists even though they generally were not directly concerned with environmental problems associated with modernity, such as pollution, tropical deforestation, species extinctions, erosion, and global warming. As people around the world became more familiar with such issues, environmental anthropologists took note and began to analyze those problems and accompanying conservation movements, especially in the developing world, which was still the primary focus of most anthropological research.

ETHNOECOLOGY

Slash-and-Burn versus Swidden Cultivation

Traditionally, anthropologists studied small communities in remote locations rather than urban societies. While much of that work examined rituals, political organizations, and kinship structures, some anthropologists focused on ethnoecology: use and knowledge of plants, animals, and ecosystems by traditional societies. Because those societies depended heavily on the natural world for food, medicine, and building materials, such knowledge was often essential to their survival.

As anthropologists, Harris and Rappaport worked to make the strange familiar by taking seemingly bizarre practices such as ritual slaughtering of pigs and sacredness of cows in India and explaining the practices within the context of the people’s culture and environment. This work explains not only how and why people do what they do, but also the advantages of their systems in the environments in which they live. An indigenous practice long demonized by the media, environmental activists, and scientists is slash-and-burn agriculture in which small-scale farmers, mostly in tropical developing countries, cut down a forest, let the wood dry for a few weeks, and then burn it, clearing the land for cultivation. Initially, the farmers plant mostly perennial crops such as rice, beans, corn, taro, and manioc. Later, they gradually introduce tree crops, and the plot is left to regrow trees while they open new fields for crops. Every year, as the soil’s fertility declines and insects become a problem in the original plot, new land is cleared to replace it. Environmentalists and developers have decried slash-and-burn cultivation as a major cause of deforestation, and governments in many tropical countries have prohibited farmers from cutting and burning forests.

Anthropologists have challenged these depictions and have documented that slash-and-burn cultivators possess detailed knowledge of their environment; their agricultural processes are sustainable indefinitely under the right conditions.[5] When there is a low population density and an adequate supply of land, slash-and-burn cultivation is a highly sustainable type of elongated crop rotation in which annuals are planted for a few years, followed first by tree crops and then by forest, rebuilding soil nutrients and mimicking natural processes of forest disturbance in which tree falls and storms periodically open up small patches of the forest. They used the term swidden cultivation instead of slash and burn to challenge the idea of the practice as inherently destructive. The surrounding forest allows the fields to quickly revert to forest thanks to seeds planted in the cleared area as birds roost in the trees and defecate into the clearing and as small rodents carry and bury the seeds. Furthermore, by mimicking natural processes, the small patches can enhance biodiversity by creating a greater variety of microclimates in a given area of forest.

The system breaks down when cleared forests are not allowed to regrow and instead are replaced with industrial agriculture, cattle raising, or logging operations that transform the open fields into pasture or permanent agricultural plots.[6] The system can also break down when small-holders are forced to become more sedentary because the amount of land they control is reduced by arrival of new migrants or government land seizures. In that case, local farmers must replant areas more frequently and soil fertility declines. A desire to plant cash crops for external markets can also exacerbate these changes because food is no longer grown solely for local consumption and more land is put into agriculture. Anthropologists’ studies uncovered the sustainability of these traditional practices, which were destructive only when outside forces pressured local farmers to modify their traditional farming systems.

Plants, People, and Culture

One branch of ethnoecology is ethnobotany, which studies traditional uses of plants for food, construction, dyes, crafts, and medicine. Scientists have estimated that 60 percent of all of the current medicinal drugs in use worldwide were originally derived from plant materials (many are now chemically manufactured). For example, aspirin came from the bark of willow trees and an important muscle relaxant used in open-heart surgery was developed from curare, the poison used on arrows and darts by indigenous groups throughout Central and South America. In light of such discoveries, ethnobotanists traveled to remote corners of the world to document the knowledge of shamans, healers, and traditional medical experts. They have also looked at psychoactive plants and their uses across cultures.

Ethnobotanical work is interdisciplinary, and while some ethnobotanists are anthropologists, many are botanists or come from other disciplines. Anthropologists who study ethnobotany must have a working knowledge of scientific methods for collecting plant specimens and of botanical classification systems and basic ecology. Similarly, archaeologists and paleobotanists study prehistoric people’s relationships and use of plants, especially in terms of domestication of plants and animals.

The Kayapó project is a famous ethnobotanical study organized by Darrell Posey and a group of twenty natural and social scientists who examined how the Kayapó people of Brazil understood, managed, and interacted with the various ecosystems they encountered as the region was transformed from a dry savanna-like Cerrado to Amazonian rainforest.[7] By documenting Kayapó names for different ecosystems and methods they used to drop seeds and care for certain plants to expand islands of forest in the savanna, the project illustrated the complex ways in which indigenous groups shape the environments in which they live by documenting how the Kayapó cared for, managed, and enhanced forests to make them more productive.

Posey was also an activist who contributed to drafting of the Declaration of Belem, which called for governments and corporations to respect and justly compensate the intellectual property rights of indigenous groups, especially regarding medicinal plants. He accompanied Kayapó leaders to Washington, D.C., to protest construction of a large dam using funds from the World Bank. Pressure from numerous international groups led to a halt in the dam’s construction (plans for the dam have recently been resurrected). Posey’s identification of the Kayapó as guardians of the rainforest provided a powerful symbol that resonated with Western ideas of indigeneity and the moral high ground of environmental conservation.

In recent years, some anthropologists have questioned whether the idea of indigenous people having an innate positive connection to the environment—what some call the myth of the ecologically noble savage—is accurate.

The Myth of the Ecologically Noble Savage

The image of the noble savage developed many centuries ago in Western culture. From the beginning of European exploration and colonialism, Europeans described the “natives” they encountered primarily in negative terms, associating them with sexual promiscuity, indolence, cannibalism, and violence. The depictions changed as Romantic artists and writers rejected modernity and industrialization and called for people to return to an idealized, simpler past. That reactionary movement also celebrated indigenous societies as simple people living in an Eden-like state of innocence. French painter Paul Gauguin’s works depicting scenes from his travels to the South Pacific are typical of this approach in their celebration of the colorful, easygoing, and natural existence of the natives. The continuing influence of these stories is evident in Disney’s portrayal of Pocahontas and James Cameron’s 2009 film Avatar in which the primitive Na`vi are closely connected to and defenders of an exotic and vibrant natural world. Cameron’s depiction, which includes a sympathetic anthropologist, criticizes Western capitalism as willing to destroy nature for profit.

Despite its positive portrayals of indigenous groups, the idea of the ecologically noble savage tends to treat indigenous peoples as an imagined “other” constructed as the opposite of Western culture rather than endeavoring to understand the world views and complexities of indigenous cultures. Similarly, a naive interpretation of indigenous environmentalism may merely project an imaginary Western ideal onto another culture rather than make a legitimate observation about that culture on its own terms.

The Kayapó in the Amazon and another group known as the Penan, who live in the Indonesian rainforest, were both confronted in the past by plans to open logging roads in their traditional territories and build dams that would flood vast amounts of their land. These indigenous communities organized, sometimes with the aid of anthropologists who had connections to media and environmental organizations, to protest the forest. The combination of two causes—rainforest conservation and indigenous rights—was powerful, successfully grabbing media attention and raising money for conservation. Their success led to later instances of indigenous groups joining efforts to halt large-scale development projects. These movements were especially powerful symbolically because they articulated the longstanding Western idea of the environmentally noble savage as well as growing environmental concerns in Europe and North America. Beth A. Conklin and Laura R. Graham, “The Shifting Middle Ground: Amazonian Indians and Eco‐Politics,” American Anthropologist 97 no. 4 (1995): 695–710.

Some anthropologists have noted that these alliances were often fragile and rested on an imagined ideal of indigenous groups that was not always accurate. The Western media, they argue, imagined indigenous groups as ecologically noble savages, and the danger in that perspective is that the indigenous communities would be particularly vulnerable if they lost that symbolic purity and the power that came with it. The image of ecologically noble savages could break down if they were seen as promoting any kind of non-environmental practices or became too involved in messy national politics. Furthermore, indigenous groups’ alliances with international activists tended to cast doubt on their patriotism and weaken their position in their own countries. Though these indigenous groups achieved visibility and some important victories, they remained vulnerable to negative press and needed to carefully manage their images.

It is important to note that depictions such as the ecologically noble savage rely on an overly simplistic portrayal of the indigenous “other.” For example, some indigenous groups have been portrayed as inherently environmentalist even when they hunt animals that Western environmentalists want to preserve. Often, the more important questions for indigenous groups revolve around land rights and political sovereignty. Environmental concerns are associated with those issues rather than existing separately. The ramifications of these differences are explained in the next section, which discusses the people-versus-parks debate.

- Maria Panakhyo and Stacy McGrath, “Ecological Anthropology,” in Anthropological Theories: A Guide Prepared by Students for Students (University of Alabama), https://anthropology.ua.edu/theory/ecological-anthropology/ ↵

- Leslie White, “Energy and the Evolution of Culture,” in Anthropological Theory: An Introductory History. eds. R. Jon McGee and Richard L. Warms (Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 2000), 249. ↵

- Julian Steward, “The Patrilineal Band,” in Anthropological Theory: An Introductory History, eds. R. Jon McGee and Richard L. Warms (Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 2000), 228–242. ↵

- Marvin Harris, “The Cultural Ecology of Indian’s Sacred Cattle,” in Anthropological Theory: An Introductory History, eds. R. Jon McGee and Richard L. Warms (Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 2000), 287. ↵

- Harold Conklin, Hanunoo Agriculture. A Report on an Integral System of Shifting Cultivation in the Philippines (New York, United Nations, 1957). ↵

- Richard Reed, “Forest Development and the Indian Way,” in Conformity and Conflict: Reading in Cultural Anthropology, eds. James Spradley and David McCurdy, 105-115 (New York: Pearson, 2011). ↵

- Darrell A. Posey, Kayapó Ethnoecology and Culture (New York: Routledge, 2003). ↵