9.3 Gender

Culture and Psychology

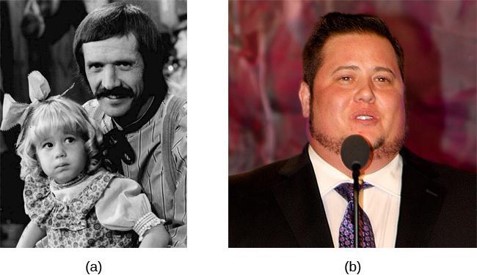

Generally, our psychological sense of being male and female, gender identity corresponds to our biological sex. This is known as cisgender. This is not true for everyone. Transgender individuals’ gender identities do not correspond with their birth sexes. Transgendered males assigned the sex female at birth have a strong emotional and psychological connection to the forms of masculinity in their society that they identify their gender as male. A parallel connection to femininity exists for transgendered females.

A binary or dichotomous view of gender (masculine or feminine) is specific to some cultures, like the United States, but it is not universal. In some cultures there are additional gender variations resulting in more than two gender categories. For example, Samoan culture accepts what they refer to as a third gender. Fa’afafine, which translates as “the way of the woman,” is a term used to describe individuals who are born biologically male but embody both masculine and feminine traits. Fa’afafines are considered an important part of Samoan culture. In Thailand, you can be male, female, or kathoey (Tangmunkongvorakul, Banwell, Carmichael, Utomo, & Sleigh, 2010) and in Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Bangladesh transgender females are referred to as hijras, recognized by their governments as a third gender (Pasquesoone, 2014).

Because gender is so deeply ingrained culturally, it is difficult to determine the prevalence of transgenderism in society. Rates of transgender individuals vary widely around the world (see Table 1) and are shaped by social norms and cultural values. Transgendered individuals, who wish to alter their bodies through medical interventions such as surgery and hormonal therapy, so that their physical being is better aligned with their gender identity, are called transsexuals. Not all transgendered individuals choose to alter their bodies. Many will maintain their original anatomy but may present themselves to society as the opposite gender.

| Nation | Transgender People per 100, 000 |

| Sweden | .17 |

| Poland | .26 |

| Ireland | 1.4 |

| Japan | 1.4 |

| India | 167 |

| Thailand | 333 |

| United States | 476 |

| Malaysia | 1, 333 |

There is no single, conclusive explanation for why people are transgendered. Some hypotheses suggest biological factors such as genetics, or prenatal hormone levels, as well as social and cultural factors, such as childhood and adulthood experiences. Most experts believe that all of these factors contribute to a person’s gender identity (American Psychological Association, 2008). Unfortunately, transgendered and transsexual individuals frequently experience discrimination based on their gender identity and are twice as likely to experience assault or discrimination as non-transgendered individuals. Transgendered individuals are also one and a half times more likely to experience intimidation (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 2010) and be the victim of violent crime.

Gender Differences

Differences between males and females can be based on (a) actual gender differences (i.e., men and women are actually different in some abilities), (b) gender roles (i.e., differences in how men and women are supposed to act), or (c) gender stereotypes (i.e., differences in how we think men and women are). Sometimes gender stereotypes and gender roles reflect actual gender differences, but sometimes they do not.

In terms of language and language skills, girls develop language skills earlier and know more words than boys; however this does not translate into long-term differences. Girls are also more likely than boys to offer praise, to agree with the person they’re talking to, and to elaborate on the other person’s comments. Boys, in contrast, are more likely than girls to assert their opinion and offer criticisms (Leaper & Smith, 2004). In terms of temperament, boys are slightly less able to suppress inappropriate responses and slightly more likely to blurt things out than girls (Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, & Van Hulle, 2006).

With respect to aggression, boys exhibit higher rates of unprovoked physical aggression than girls, but no difference in provoked aggression (Hyde, 2005). Some of the biggest differences involve the play styles of children. Boys frequently play organized rough-and-tumble games in large groups, while girls often play fewer physical activities in much smaller groups (Maccoby, 1998). There are also differences in the rates of depression, with girls much more likely than boys to be depressed after puberty. After puberty, girls are also more likely to be unhappy with their bodies than boys.

There is considerable variability between individual males and females. Also, even when there are average group differences, the actual size of most of these differences is quite small. This means, knowing someone’s gender does not help much in predicting his or her actual traits.

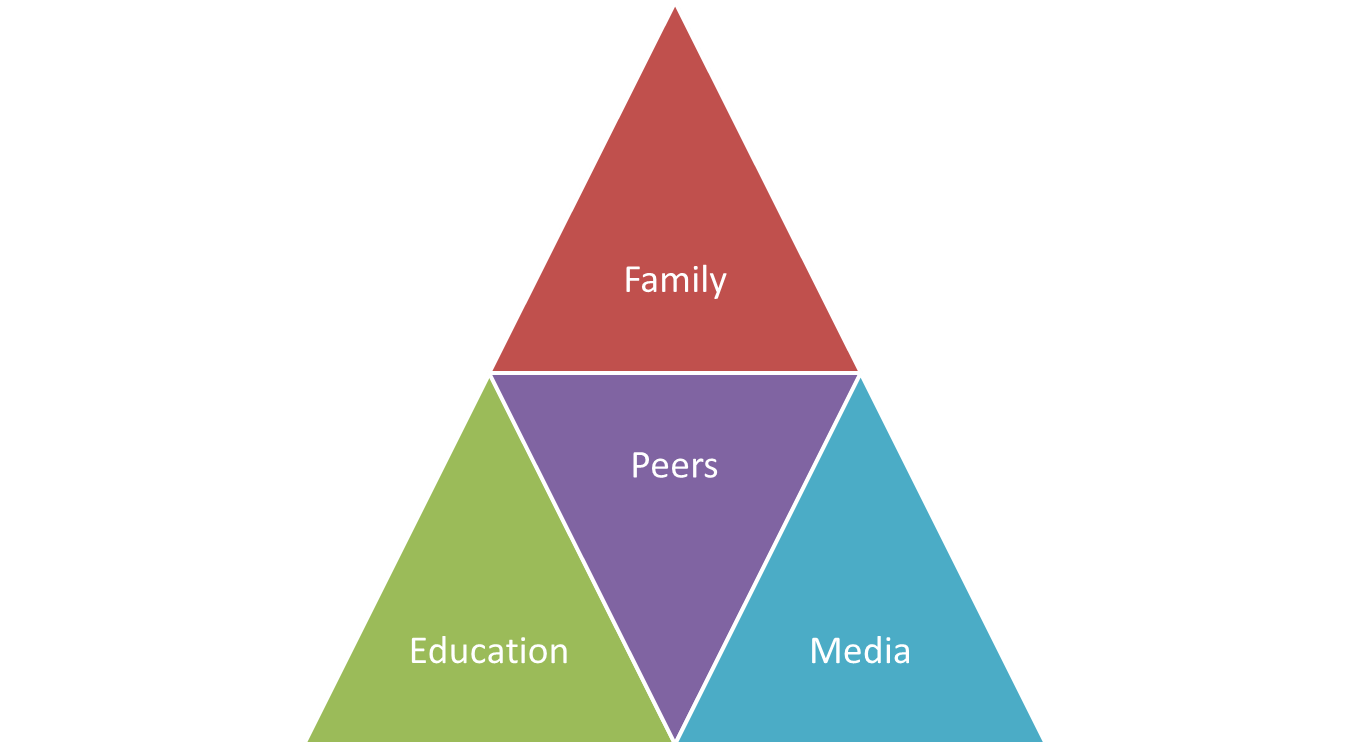

Gender Enculturation Agents

Regardless of theory, observing, organization and learning about gender occurs through four major agents of socialization: family, education, peers and media. Each agent reinforces gender roles by creating and maintaining normative expectations for gender-specific behavior. Exposure also occurs through secondary agents such as religion and the workplace.

Family

Family is the first agent of socialization and enculturation. There is considerable evidence that parents socialize sons and daughters differently. A meta-analysis of research from the United States and Canada found that parents most frequently treated sons and daughters differently by encouraging gender-stereotypical activities (Lytton & Romney, 1991). Fathers, more than mothers, are particularly likely to encourage gender-stereotypical play, especially in sons. Parents also talk to their children differently based on stereotypes. For example, parents talk about numbers and counting twice as often with sons than daughters (Chang, Sandhofer, & Brown, 2011) and talk to sons in more detail about science than with daughters. Parents are also much more likely to discuss emotions with their daughters than their sons.

Girls may be asked to fold laundry, cook meals or perform duties that require neatness and care. It has been found that fathers are firmer in their expectations for gender conformity than are mothers, and their expectations are stronger for sons than they are for daughters (Kimmel, 2000). This is true in many types of activities, including preference of toys, play styles, discipline, chores, and personal achievements. As a result, boys tend to be particularly attuned to their father’s disapproval when engaging in an activity that might be considered feminine, like dancing or singing (Coltrane and Adams, 2008).

It should be noted that parental socialization and normative expectations vary along lines of social class, race, and ethnicity. Research in the United States has shown that African American families, for instance, are more likely than Caucasians to model an egalitarian role structure for their children (Staples and Boulin Johnson, 2004). Even when parents set gender equality as a goal, there may be underlying indications of inequality. For example, when dividing up household chores, boys may be asked to take out the garbage, take care of the yard or perform other tasks that require strength or toughness.

Peers

As noted earlier, peer socializations can also serve to reinforce gender norms of a culture. Children learn at a very young age that there are different expectations for boys and girls. When children do not conform to the appropriate gender role, they may experience negative consequences like criticism, bullying or rejection by their peers. Boys and young men are more likely to experience intense, negative peer responses when they do not follow traditional gender norms (Coltrane and Adams, 2008; Kimmel, 2000).

Education

The reinforcement of gender roles and stereotypes continues once a child reaches school age. Studies suggest that gender socialization still occurs in schools today, perhaps in less obvious forms (Lips, 2004). Teachers may not even realize that they are acting in ways that reproduce gender-differentiated behavior patterns but any time students are asked to arrange their seats or line up according to gender, teachers are reinforcing that boys and girls should be treated differently (Thorne, 1993). Even in levels as low as kindergarten, schools subtly convey messages to girls indicating that they are less intelligent or less important than boys.

For example, in a study involving teacher responses to male and female students, data indicated that teachers praised male students far more than they praised female students. Additionally, teachers interrupted girls more and provided boys with more opportunities to expand on their ideas (Sadker & Sadker, 1994). Schools often reinforce the polarization of gender by positioning girls and boys in competitive arrangements – like a “battle of the sexes” competition.

Media

In television and movies, women tend to have less significant roles and are often portrayed as wives or mothers. When women are given a lead role, they are often one of two extremes: a wholesome, saint-like figure or a malevolent, hypersexual figure (Etaugh and Bridges, 2003). Weisbuch and Ambady (2009) demonstrated that nonverbal behavior on television can communicate culturally shared attitudes and biases about women and ideal body images. Television commercials and other forms of advertising also reinforce inequality and gender-based stereotypes. Women are almost exclusively present in ads promoting cooking, cleaning, or child care-related products (Davis, 1993). Think about the last time you saw a man star in a dishwasher or laundry detergent commercial. In general, women are underrepresented in roles that involve leadership, intelligence, or emotional stability. In mainstream advertising, however, themes intermingling violence and sexuality are quite common (Kilbourne, 2000).

Gender inequality is pervasive in children’s movies (Smith, 2008). Research indicates that of the 101 top-grossing children’s movies released between 1990 and 2005, three out of four (75%) characters were male, only seven (7%) were near being gender balanced.