8.1 Introduction to Personality

Culture and Psychology

You have probably noticed that some people are very social and outgoing while others are very quiet and reserved. Some people seem to worry a lot while others never seem to get anxious. Each time we use words like social, outgoing, reserved or anxious to describe people around us, we are talking about a person’s personality. Personality is one of the things that make us unique from one another. Our personalities are thought to be long term, stable, and not easily changed (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005) leading some psychologists argue that personality is heritable and biological.

Personality is not the same thing as character, which refers to qualities that a culture considers good and bad. Temperament, as we learned earlier, is hereditary and includes sensitivity, moods, irritability, and distractibility. In this way, temperament can be seen as part of our personality and offers support for biological and universal aspects of personality.

Once we understand someone’s personality, we can predict how that person will behave in a variety of situations. Think about what it takes to be successful in college. You might say that intelligence is factor in college success and you would be correct but personality researchers have also found that traits like Conscientiousness play an important role in college success. Highly conscientious individuals study hard, get their work done on time, and are less distracted by nonessential activities that take time away from school work. Over the long term, this consistent pattern of behaviors can add up to meaningful differences in academic and professional development. Personality traits are not just a useful way to describe people; they actually help psychologists predict if someone is going to be a good worker, how long he or she will live, and the types of jobs and activities the person will enjoy.

There are many psychological perspectives that try to explain personality including behaviorist, humanist and sociocultural perspectives. This chapter will focus solely on the trait theory of personality and how combinations of traits create unique personality profiles. This chapter will also review how personality traits are identified and measured across cultures.

Trait Theory

Personality traits reflect people’s characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Trait theory in psychology rests on the idea that people differ from one another based on the strength and intensity of basic trait dimensions. There are three criteria that characterize personality traits: (1) consistency, (2) stability, and (3) individual differences.

- Individuals must be somewhat consistent across situations in their behaviors related to the trait. For example, if they are talkative at home, they tend also to be talkative at work.

- A trait must also be somewhat stable over time as demonstrated behaviors related to the trait. For example, at age 30 if someone is talkative they will also tend to be talkative at age 40.

- People differ from one another on behaviors related to the trait. People differ on how frequently they talk and so personality traits such as talkative exist.

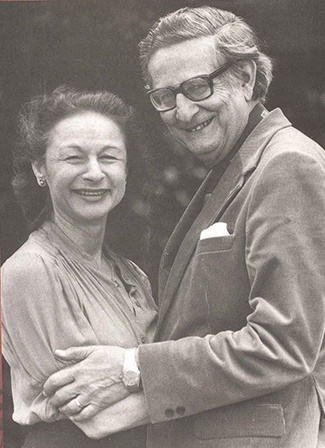

A major challenge for trait theorists was how to identify traits. They started by generating a list of English adjectives (after reading about bias in Chapter 3 I bet you can see a problem here). Early trait theorists Allport and Odbert identified about 18, 000 words in the English language that could describe people (Allport & Odbert, 1936). The list was later reduced to 4,500 by Allport but even this was far too many traits. In an effort to make the list of traits more manageable, Raymond Cattell (1946, 1957) narrowed the list to 16 factors and developed a personality assessment called the 16PF. Later, psychologists Hans and Sybil Eysenck focused on temperament (Eysenck, 1990, 1992; Eysenck and Eysenck, 1963) and hypothesized two specific personality dimensions: extroversion/introversion and neuroticism/stability.

While Cattell’s 16 factors may be too broad, the 2-factor system proposed by the Eysenck’s has been criticized for being too narrow. Another personality theory, called the Five Factor Model (FFM), effectively hits a middle ground. The five factors are commonly referred to as the Big Five personality traits (McCrae & Costa, 1987). It is the most popular theory in personality psychology today and the most accurate approximation of the basic trait dimensions (Funder, 2010). Traits are scored along a continuum, from high to low rather than present or absent (all or none). This means that when psychologists talk about Introverts (e.g., quiet, withdrawn, reserved) and Extroverts (e.g., outgoing, social, talkative), they are not really talking about two distinct types of people but rather they are talking about people who score relatively low or relatively high along a continuous dimension.

The five traits are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. A helpful way to remember the traits is by using the mnemonic OCEAN.

Scores on the Big Five traits are mostly independent which means that a person’s position on the continuum for one trait tells very little about their standing on the other traits. For example, a person can be extremely high in Extraversion and be either high or low on Neuroticism. Similarly, a person can be low in Agreeableness and be either high or low in Conscientiousness. In the FFM you need five scores to describe most of an individual’s personality.