8.3 Self & Culture

Culture and Psychology

At the foundation of all human behavior is the self—our sense of personal identity and of who we are as individuals. Because an understanding of the self is so important, it has been studied for many years by psychologists (James, 1890; Mead, 1934) and is still one of the most important and most researched topics in psychology (Dweck & Grant, 2008; Taylor & Sherman, 2008).

Identity

Identity refers to the way individuals understand themselves as part of a social group. It is a universal construct and depends on how we view ourselves and how we are recognized by others. Identity may be acquired indirectly from parents, peers, and other community members or more directly through enculturation. A person may hold multiple identities such as teacher, father, or friend. Each position has its own meanings and expectations that are internalized as identity. In this way, the specific content of any individual’s or group’s identity is culturally determined. Also, forming a connection with your identity is influenced by your culture. For example, in the United States it is common to link identity with a particular ethnic or racial group (e.g., Hispanic, African American, Asian American, and Jewish American among others) but we should remember that these categories are products of immigration and history. The history is unique to the United States so individuals from other cultures do not identify with the same cultural groups (Matsumoto & Luang, 2013).

We should also think of identity as dynamic and fluid. It can change depending on the context and the culture. Think about it – when someone asks you where you are from, if you are in a foreign country you might say the United States. In a different situation you might say that you are from California even though you were actually born in Kansas and in a very small state like Hawaii you might identify by your high school (Matsumoto & Luang, 2013).

Our personal identity is the way that we understand ourselves and is closely related to our concept of self. Social identity reflects our understanding that we are part of social groups. Our sense of self is linked to how we see the world around us and how we see our relationships.

Self

Some nonhuman animals, including chimpanzees, orangutans, and perhaps dolphins, have at least a primitive sense of self (Boysen & Himes, 1999). We know this because of some interesting experiments that have been done with animals. In one study (Gallup, 1970), researchers painted a red dot on the forehead of anesthetized chimpanzees and then placed the animals in a cage with a mirror. When the chimps woke up and looked in the mirror, they touched the dot on their faces, not the dot on the faces in the mirror. This action suggests that the chimps understood that they were looking at themselves and not at other animals, and thus we can assume that they are able to realize that they exist as individuals. Most other animals, including dogs, cats, and monkeys, never realize that it is themselves they see in a mirror.

Infants who have similar red dots painted on their foreheads recognize themselves in a mirror in the same way that chimps do, and they do this by about 18 months of age (Asendorpf, Warkentin, & Baudonnière, 1996; Povinelli, Landau, & Perilloux, 1996). The child’s knowledge about the self continues to develop as the child grows. By two years of age, the infant becomes aware of his or her gender as a boy or a girl. At age four, the child’s self-descriptions are likely to be based on physical features, such as hair color, and by about age six, the child is able to understand basic emotions and the concepts of traits, being able to make statements such as “I am a nice person” (Harter, 1998).

By the time children are in grade school, they have learned that they are unique individuals, and they can think about and analyze their own behavior. They also begin to show awareness of the social situation—they understand that other people are looking at and judging them the same way that they are looking at and judging others (Doherty, 2009).

When measuring personality, we need to remember that when comparing traits across cultures we are using group averages. There are certainly differences in personality traits between cultural groups but there is still a lot variability that exists within a specific culture (McCrae et al., 2005). Individualist cultures and collectivist cultures place emphasis on different basic values. People who live in individualist cultures tend to believe that independence, competition, and personal achievement are important. Individuals in Western nations such as the United States, England, and Australia score high on individualism (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmier, 2002). People who live in collectivist cultures value social harmony, respectfulness, and group needs over individual needs. Individuals who live in countries in Asia, Africa, and South America score high on collectivism (Hofstede, 2001; Triandis, 1995). These values influence personality. For example, Yang (2006) found that people in individualist cultures displayed more personally oriented personality traits, whereas people in collectivist cultures displayed more socially oriented personality traits.

We also need to remember that people do not act consistently from one situation to the next and people are influenced by situational forces and culture. For example, individuals who score high on the Extraversion scale are likely to be outgoing and enjoy socializing but where, when and how they socialize will be influenced by culture (McCrae et al., 1998).

Although we all define ourselves in relation to these three broad categories of characteristics—physical, personality, and social – some interesting cultural differences in the relative importance of these categories have been shown in people’s responses to the TST. For example, Ip and Bond (1995) found that the responses from Asian participants included significantly more references to themselves as occupants of social roles (e.g., “I am Joyce’s friend”) or social groups (e.g., “I am a member of the Cheng family”) than those of American participants. Similarly, Markus and Kitayama (1991) reported that Asian participants were more than twice as likely to include references about other people in their self-concept as did their Western counterparts. This greater emphasis on either external or social aspects of the self-concept reflects the relative importance that collectivistic and individualistic cultures place on an interdependence versus independence (Nisbett, 2003).

Interestingly, bicultural individuals who report acculturation to both collectivist and individualist cultures show shifts in their self-concept depending on which culture they are primed to think about when completing the TST. For example, Ross, Xun, and Wilson (2002) found that students born in China but living in Canada reported more interdependent aspects of themselves on the TST when asked to write their responses in Chinese, as opposed to English. These culturally different responses to the TST are also related to a broader distinction in self-concept, with people from individualistic cultures often describing themselves using internal characteristics that emphasize their uniqueness, compared with those from collectivistic backgrounds who tend to stress shared social group memberships and roles. In turn, this distinction can lead to important differences in social behavior.

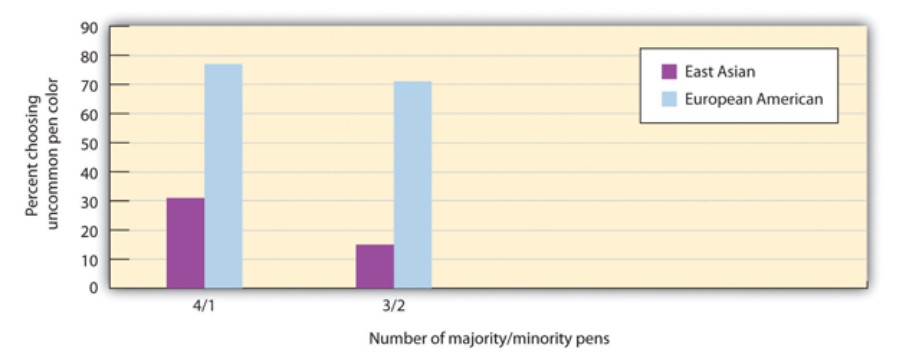

One simple yet powerful demonstration of cultural differences in self-concept affecting social behavior is shown in a study that was conducted by Kim and Markus (1999). In this study, participants were contacted in the waiting area of the San Francisco airport and asked to fill out a short questionnaire for the researcher. The participants were selected according to their cultural background: about one-half of them indicated they were European Americans whose parents were born in the United States, and the other half indicated they were Asian Americans whose parents were born in China and who spoke Chinese at home.

After completing the questionnaires (which were not used in the data analysis except to determine the cultural backgrounds), participants were asked if they would like to take a pen with them as a token of appreciation. The experimenter extended his or her hand, which contained five pens. The pens offered to the participants were either three or four of one color and one or two of another color (the ink in the pens was always black). As shown in Figure 1 and consistent with the hypothesized preference for uniqueness in Western, but not Eastern cultures, the European Americans preferred to take a pen with the more unusual color, whereas the Asian American participants preferred one with the more common color.

Through these and other experiments two dimensions of self-concept emerged, the independent construal (concept) and the interdependent concept. Western, or more individualist cultures, view the self as separate and focus on self, independence, autonomy and self-expression are reinforced through social and cultural norms. This is the independent self-concept. Non-western or collectivistic cultures view the self as interdependent and inseparable from social context and individuals socialized to value interconnectedness consider the thoughts and behaviors of others. Fitting in is valued over standing out.

Results from the TST studies described earlier provide additional support for the role of culture in shaping self-concept. Different demands that cultures place on individual members means that individuals integrate, synthesize, and coordinate worlds differently, producing differences in self-concept. Variations in self-concepts occur because different cultures have different rules of living and exist within different environments (natural habitat).

Results from the TST studies described earlier provide additional support for the role of culture in shaping self-concept. Different demands that cultures place on individual members means that individuals integrate, synthesize, and coordinate worlds differently, producing differences in self-concept. Variations in self-concepts occur because different cultures have different rules of living and exist within different environments (natural habitat).

Intra-cultural Differences in Self-Concept

Cultural differences in self-concept have even been found in people’s self-descriptions on social networking sites. DeAndrea, Shaw, and Levine (2010) examined individuals’ free-text self-descriptions in the About Me section in their Facebook profiles. Consistent with the researchers’ hypothesis, and with previous research using the TST, African American participants had the most the most independently (internally) described self-concepts, and Asian Americans had the most interdependent (external) self-descriptions, with European Americans in the middle.

As well as indications of cultural diversity in the content of the self-concept, there is also evidence of parallel gender diversity between males and females from various cultures, with females, on average, giving more external and social responses to the TST than males (Kashima et al., 1995). Interestingly, these gender differences have been found to be more apparent in individualistic nations than in collectivistic nations (Watkins et al., 1998).

Indigenous Personality

Much of this chapter has been dedicated to the etic approach for understanding personality which posits that personality is innate, biological and universal but still acknowledges that culture plays an important in shaping personality by way of geography (environment), resources, and social supports.

Indigenous Personality is a perspective that suggests personality can only be understood and interpreted within the context of the culture. In this way personality is considered emic, meaning that it is culturally specific and can only understood within the culture from which it originates. This means that personality is not something that can be measured by a universal test.

The indigenous approach came about in reaction to the dominance of Western approaches to the study of personality in non-Western settings (Cheung et al., 2011). Because Western-based personality assessments cannot fully capture the personality constructs of other cultures, the indigenous model has led to the development of personality assessment instruments that are based on constructs relevant to the culture being studied (Cheung et al., 2011). Although there is debate within the indigenous psychology movement about whether indigenous psychology represents a more universalistic or a more relativistic approach (Chakkarath, 2012), most of these 10 characteristics are advocated by the majority of those in the indigenous psychology movement.

Beyond East-West Differences

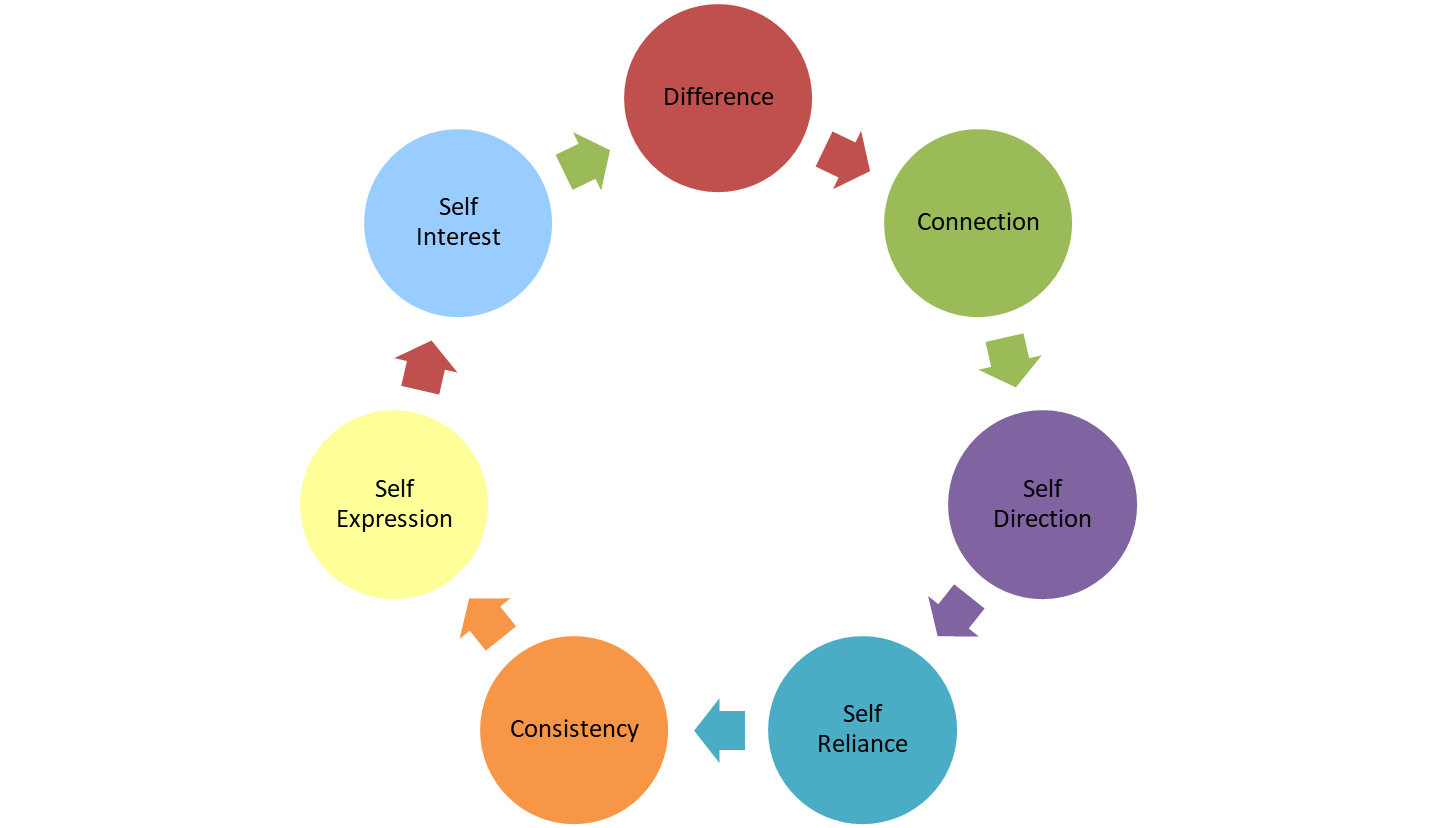

The work by Markus and Kitayama (1991) has had a major effect on social, personality and developmental psychology and raised awareness for cultural considerations in psychology. Despite the positive impact, there has been limited empirical support for independent and interdependent self-construals (Matsumoto, 1999) with some studies reporting contradictory findings. Recent research conducted by 71 researchers, across 33 countries and encompassing 55 cultural groups challenged the dichotomous view first proposed by Markus and Kitayama. The researchers conducted a series of studies (Vignoles…. 2016) that examined a single dimension of Independent/Interdependent, Western cultures as wholly independent, the relationship between individualist and collectivist cultures and Independent/Interdependent self-construals, as well as the role of religious heritage and socioeconomic development of cultures. Using data from over 7,000 adults, the authors identified seven dimensions that encompass both independent and interdependent self-construals:

- Difference

- Connection

- Self-Direction

- Self-Reliance

- Consistency

- Self-Expression

- Self-Interest

At the level of the individual these seven dimensions represent the different ways that we see ourselves and our relationships with other people. The dimensions can also represent cultural norms about self that are reinforced and maintained by cultural practices and social structures.

When the researchers tested the 7-dimension model, their results contradicted many long-held beliefs about independent, individualistic, interdependent and collectivist cultures. First, Western cultures scored above average on five of the dimensions but were below average on the dimensions self-reliance and consistency. Thus, the common view that Western cultures are wholly independent was not supported.

Latin American cultures had scores very similar to Western cultures on the difference and self-expression dimensions but scored higher on consistency and self-interest which also challenged the common view of Latin America as wholly interdependent. The economically poorest samples in the study scored highest on self-interest and were negatively associated with individualism, whereas Western cultures scored high on commitment to others which challenges the view that rich Western cultures are selfish.

Religious heritage was also an important variable in the study. Muslim and Catholic samples had very distinct dimension profiles that showed high scores for consistency. This may be related to the tenets of both faiths that salvation is related to behaviors so behaving consistently – across different situations and settings would be important.

The results of Vignoles and colleagues demonstrated that self, whether measured at the individual level or cultural level, is not binary. Independence and interdependence is a complex interaction of heritage, socioeconomic development, settlement patterns, and ecological contexts. By moving away from a dichotomous view of self, psychologists have an opportunity to expand our understanding of self and its relationship to culture.